![]()

A Remarkable Decade for Real Estate

The decade from 2000 to 2010 was the most exciting, remarkable and ultimately disastrous period for real estate since the end of the Second World War. Those dramatic ten years witnessed the world’s first coordinated real estate boom and slump. Real estate cycles are a common feature of free market economic development and, from time to time, they badly destabilise individual economies. In the years before 2007, real estate values were driven to peak levels across the greater part of the developed world. When prices collapsed in 2008, by up to 60% in some countries, the global financial system was almost destroyed and a new Great Depression ushered in. At the time of writing (mid-2011), the aftershocks of the great financial crisis (GFC) linger on, in the sovereign debt crisis of Southern Europe and in the moribund housing market of the USA. Unemployment in the developed world, the social cost of the crisis, remains very high.

For real estate, the 2000s started rather unpromisingly amidst the global recession created by the bursting of the ‘dot-com’ bubble. Between 1996 and the end of 1999, on the back of easy money, buoyant global growth and widespread optimism about the potential of the Internet, global stock markets rose by 24%. Between 2000 and 2003, all of these gains were reversed, as world markets fell by 30%. The swings in value were much greater in the stock markets of the USA and the UK. Investment fell and unemployment rose. Contraction in the corporate sector led to a fall in demand for business and commercial space and a steep drop in rents. The real estate recession of the early 2000s was particularly severe in the office sector, because demand for offices depends directly on the state of the financial markets.

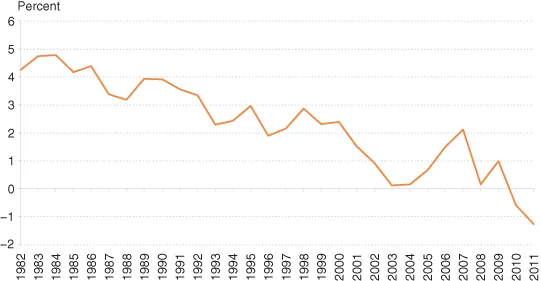

It is worth reflecting on the ‘wreckage’ of the dot-com slump, because it is here that the real estate story of the 2000s begins. Since the early 1990s, OECD central banks have been haunted by the spectre of Japan. Between 1950 and 1989, Japan was one of the word’s fastest-growing and most dynamic economies. Towards the end of its long expansion, its stock market and land market dramatically boomed and slumped. Since then, Japan has been unable to shrug off slow growth, deflation and a chronic inability to create jobs. The reasons for Japan’s 20-year deflation are complex, but most agree that monetary policy was too tight in the post-bubble period. This is a mistake that OECD central banks do not wish to repeat. So, in the wake of the stock market crash of 2000, interest rates were cut aggressively to support asset values, boost confidence and revive business and consumer spending. Figure 1.1 shows OECD real interest rates over the period: it is the key to understanding the events of the 2000s and the GFC.

It is often said that using interest rates to stimulate an economy is like dragging a brick with an elastic band: nothing happens for a while and then the brick jumps up and hits you on the back of the head. This is how it played out in the real estate sector. The period 2001 to 2003 saw depression in most asset markets; confidence was weak as the global economy worked its way through the aftermath of the tech-crash. Suddenly, in 2003 a ‘wall of money’ hit the real estate sector. Investors, nervous of the stock market, were not prepared to tolerate the low returns on cash and bonds that resulted from super-loose monetary policy. The ‘search for yield’ was on and real estate was suddenly the most favoured asset class. The long, globally coordinated boom in real estate values had begun. Figure 1.2 shows a global composite yield for the retail sector and the office sector. The period from 2003 to 2008 saw a rapid and continuous appreciation of prices driven entirely by investment demand.

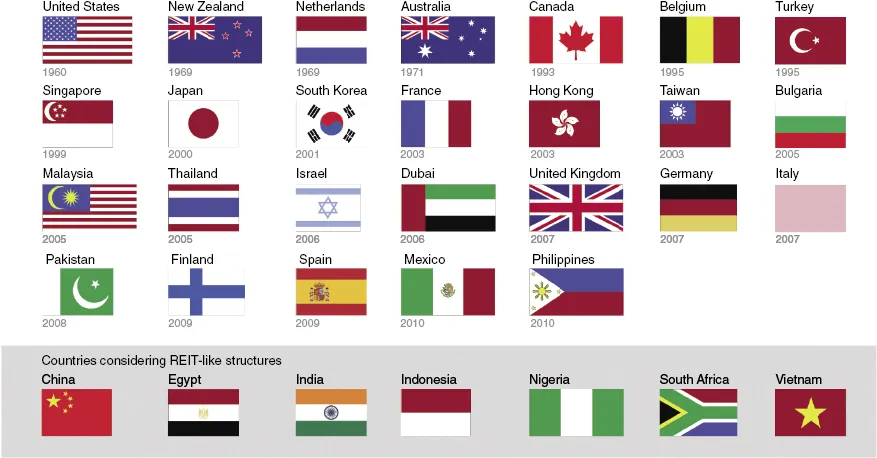

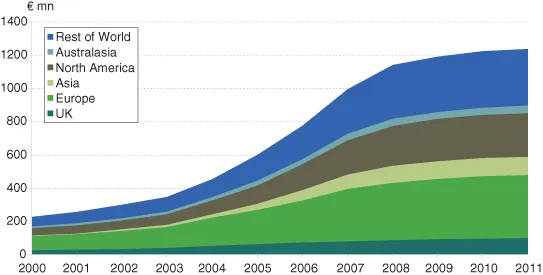

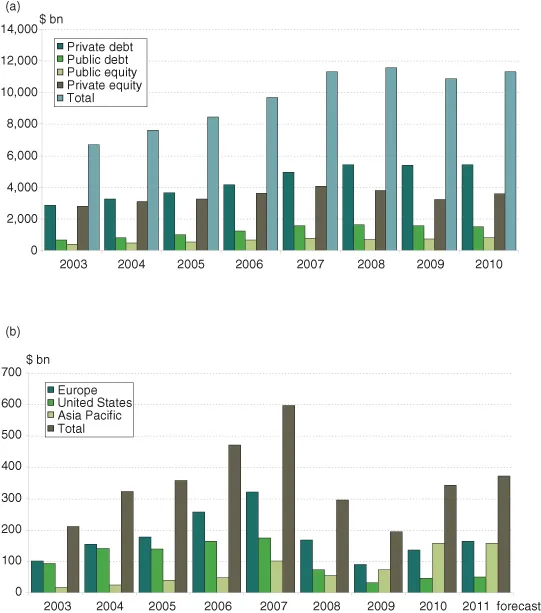

The first wave of investment was primarily driven by ‘equity’ investors; those for whom easy access to bank finance was not a key issue. These included pension funds and insurance companies, high net worth individuals, private equity funds and, increasingly, newly created sovereign wealth funds. Even small investors, through the medium of open-ended funds or other ‘retail’ vehicles, were clamorous for real estate. REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts) were prominent investors; the ten years to 2007 had seen REITs or REIT-type vehicles approved in over eight jurisdictions (figure 1.3). The period also saw the very rapid growth in unlisted real estate funds (figure 1.4). These tax transparent vehicles provided a convenient means for professional investors to deploy capital in diversified pools of real estate assets run by professional real estate managers.

‘Behind the scenes’, it was low interest rates that were fuelling the boom. Low interest rates (or expansionary monetary policy) have a ‘double impact’ on the attractiveness of real estate as an investment. First, they lower the cost of holding the asset. Second, by boosting the cash flow of occupiers, they improve the security of real estate operating income. At the time, the link between booming real estate values and super-loose monetary policy was not widely appreciated. Indeed, many market participants preferred to think about the ‘golden age of real estate’. Real estate, with its long duration and stable cash flows and increasingly good data provision, was the institutional asset of choice.

By 2005, the initial impetus to real estate values from ‘equity’ investors had been replaced by debt-driven buyers; namely, buyers with very high levels of leverage. Such ‘players’ are a feature of any rising real estate market, often originating in markets with low or negative real interest rates (where interest rates are lower than domestic inflation). In the mid-2000s, debt-driven investors from Ireland, Iceland, Spain, the USA and Israel flooded into the marketplace. Figure 1.5 shows money flows into real estate over the period, by type and destination.

Banks generally find real estate an attractive asset, but particularly when interest rates are low and economic growth is strong. Unlike businesses, real estate assets are relatively easy to appraise and assess for creditworthiness. Moreover, the market is large, and at times of rising values it can create additional lending opportunities very quickly. For instance, we estimate that the total value of real estate in the US is $7.7trn, so a 10% increase in values creates $770bn of additional ‘lending opportunities’. No other sector gives banks the ability to increase their loan books as quickly as real estate. Compounding this, as we now appreciate, banks in the OECD can operate on the assumption that that they will not have to bear the full consequences of risky lending decisions. In any case, in the mid-2000s, it became quite clear that the major lending banks had replaced carefully considered lending with market share as their main objective function. Real estate was the sector of choice.

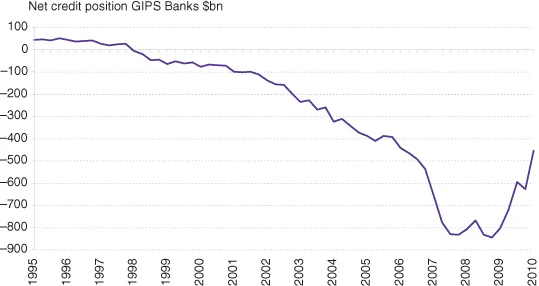

Two further factors facilitated the flow of debt into the real estate sector in the mid-2000s. One factor related to globalisation was the long-term growth in the usage by banks, in all regions, of the money markets for funding. Since the 1960s, customer deposits have fallen as a share of banks’ liabilities and certificates of deposit, repurchase agreements and commercial paper have increased. As long as the money markets were open, the banks could expand lending way beyond the level that would be supported by their own domestic deposit base. During the 2000s, at least until 2007, it was very easy for banks in countries such as Spain, Portugal and the UK to tap the money markets in order to expand lending to real estate. Moreover, on the supply side, ‘excess savings’ in other parts of Europe and Asia saw the money markets awash with liquidity. This process, which might be called the globalisation of banking, is one of the key mechanisms by which real estate markets which are local in character can be swamped by international money flows. In the lead-up to 2007, banks in high savings areas invested in banks in low savings areas, allowing the latter aggressively to expand lending (Figure 1.6).

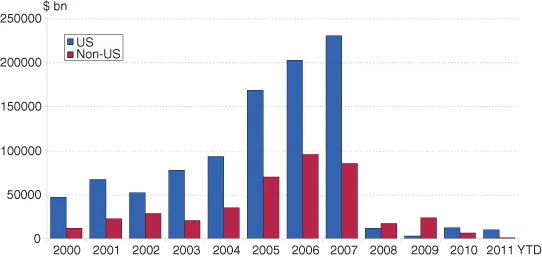

Alongside the globalisation of banking was the growth of loan securitisation. Securitisation is the process by which pools of loans, for instance real estate mortgages, are ‘bundled’ together and the rights to receive the cash flows from these loans are sold to investors. The bank that sells this collection of loans receives cash (asset), which in due course it can recycle into additional lending and it deletes the loans (assets) from its balance sheet. In principle, there is nothing wrong with this; it has been a feature of the US mortgage industry for many years. Non-bank investors get access to stable investments with a good cash yield and banks get cash to help them engage in their primary task to provide loans to those that need them. However, there are two potential flaws in securitisation. First, in the circumstances of lax supervision and extreme monetary stimulation that characterised the early and the mid-2000s, it created an incentive for banks to originate loans for the sake of creating investment products, rather than supporting commercially sensible business transactions. Second, it facilitates the ‘unseen’ build-up in leverage within a market – in this case the real estate market – because the loans are ‘off-balance sheet’. Loan securitisation was a major part of the ‘shadow banking sector’, which ballooned in the five years prior to the GFC. Figure 1.7 shows the growth of securitised real estate.

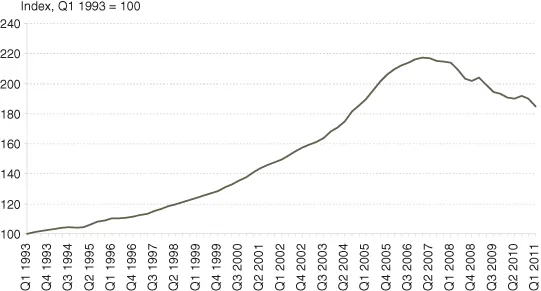

The worst excesses in real estate loan securitisation took place in the US housing market in the six years to 2007. Here, mortgage lending to the general public became aggressive to the point of being fraudulent.1 To create loans that could be securitised and sold to investors as quickly as possible, originators devised mortgage products that eliminated the need for lenders and borrowers to consider in any way, shape or form the ability of the latter to repay their debts. For instance, ‘the stated income loan’ or, as it is more notoriously known, ‘the liar loan’ allowed mortgage finance to be advanced to house buyers in extremely marginal occupations.2 Not surprisingly, US house prices, which had in any case been rising strongly since the mid-1990s due to strong job growth, surged. At the same time, the capital markets, concerned as they were to secure ‘yielding investments’, received an enhanced flow of just the sort of product they were after: mortgage-backed securities. Figure 1.8 shows the rise and fall of US house prices.

The economic factors that drive the price of houses are: the cost of mortgages (interest rates); the rate of job creation (consumer incomes); expectations of future price rises (investment motivation); and the rate of construction of new premises (supply). In late 2006 rising interest rates, falling job growth and surging new construction hit the US housing market and sent prices, albeit slowly at first, into decline for the first time in the postwar period. The impact of the fall in US house prices on global capital markets took some time to emerge, but it was profound when it did. As it turned out, numerous financial institutions, including some of the world’s best-known banks, had invested in mortgage-backed securities in general and US residential mortgage-backed securities in particular. The scale of this investment and the fact that the banks themselves had historically high levels of leverage meant that the global financial system was under serious threat. In addition, certain key insurance companies were in jeopardy, because they had insured mortgage-backed products. C...