![]()

Chapter 1

The patient with acute lung injury (ALI)

Julie Hamilton

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is the severest form of acute lung injury (ALI) and presents one of the greatest challenges to health professionals within critical care. This scenario focuses on the knowledge and skills necessary to manage the complex needs of a patient with ARDS.

Patient scenario

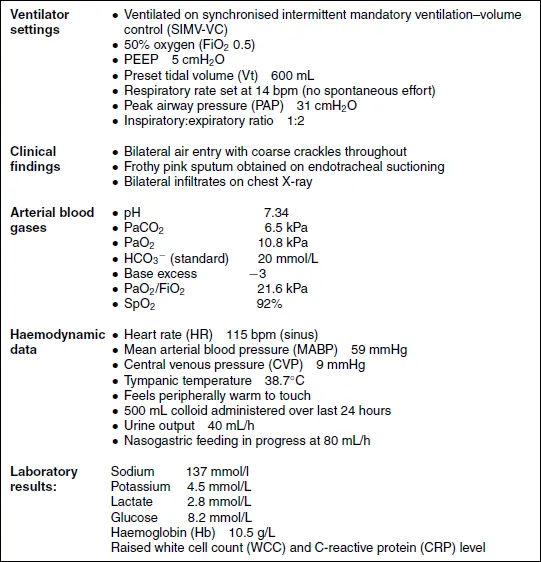

Lee Kuan Yew, a 68-year-old gentleman who weighs 75 kg, was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) following intubation in the Accident and Emergency (A&E) department for acute respiratory failure. He had been unwell for four days with shortness of breath, pleuritic pain, fever and rigours and presented to the A&E with tachypnoea, followed by dyspnoea and progressive hypoxaemia and hypercarbia. Physical examination revealed focal findings of consolidation. His past medical history was unremarkable, but he smoked 30 cigarettes per day for the past 40 years. Three days following his admission to the ICU, Lee Kuan Yew remains sedated, intubated and mechanically ventilated. Assessment findings can be seen in Table 1.1.

Reader activities

Having read this scenario, consider the following:

- How do Lee Kuan Yew's symptoms suggest that he has an ALI?

- Consider the possible causes of Mr Kuan Yew's lung injury. Outline the factors that make him at risk for the development of ALI.

- What stage of ALI do you think Mr Kuan Yew is in? Explain this using relevant pathophysiology.

- Analyse the blood gas presented. Consider the possible causes of Mr Kuan Yew's altered results.

- Do you agree with the current ventilation strategy? How would you manage Mr Kuan Yew's respiratory function?

- What therapies other than conventional ventilation can be utilised in the management of ARDS?

Table 1.1 Assessment findings.

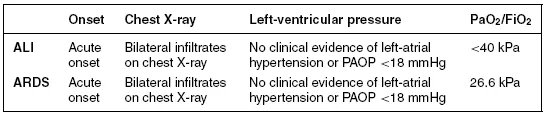

Definitions of acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

Adult respiratory distress syndrome was first described by Ashbaugh et al. in 1967 as a clinical syndrome different from other types of acute respiratory failure, with clinical characteristics of tachypnoea, hypoxaemia resistant to supplemental oxygen, diffuse alveolar infiltrates and decreased pulmonary compliance (Ashbaugh et al. 1967).

Since its initial description in 1967, the criteria for defining ALI/ARDS have changed several times. In 1988 Murray and colleagues proposed a definition which described whether the syndrome was in an acute or chronic phase, the physiological severity of pulmonary injury and the disorder associated with the development of the lung injury (Murray et al. 1988). In 1994, recognising that the study of ALI and ARDS was still hindered by the lack of a simple, uniform definition, the North American–European Consensus Conference (NAECC) published further revised definitions (Bernard et al. 1994) (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 American–European Consensus Conference Definitions of ALI/ARDS.

Source: From Bernard et al. (1994).

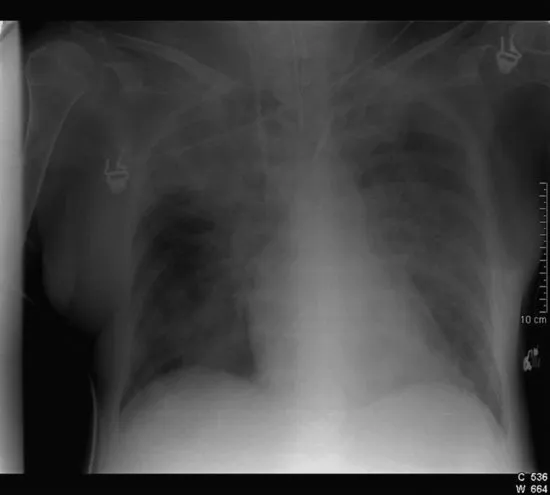

From the NAECC definition it can be deduced that Mr Kuan Yew has ARDS. He has developed acute respiratory failure requiring ventilation; he is hypoxaemic with a PaO2/FiO2 ratio of 21.6 kPa and has bilateral infiltrates on chest x-ray (see Figure 1.1).

Mr Kuan Yew does not have a pulmonary artery catheter in situ to enable determination of the pulmonary artery occlusion pressure (PAOP); however, he has no history of cardiac disease and clinically shows no signs of left-atrial hypertension such as a raised central venous pressure (CVP), although the latter can be normal in left-atrial hypertension. Mr Kuan Yew is also demonstrating symptoms of severe sepsis (see Chapter 4 for further information on sepsis), a common co-existing condition.

Pathophysiology of ALI/ARDS

Pathology

In 1972 the National Institute of Health estimated the incidence of ARDS at 60 cases per 100 000 population per year (National Heart and Lung Institute, National Institute of Health (NHL, NIH) 1972). Several robust studies since then have demonstrated a wide range of incidence rates of ARDS from 1.5 to 8.3 cases per 100 000 per year (Villar and Slutsky 1989; Garber et al. 1996). Although it could therefore be considered a rare disease, the mortality of ARDS is high, estimated to be between 34% and 65% (Estenssoro et al. 2002; Herridge et al. 2003). The incidence of ALI, however, appears more common with many patients within high dependency settings having a PaO2/FiO2 of <40 kPa. It is therefore essential that critical care nurses have an understanding of the pathophysiology and management of ALI and ARDS. The major cause of death in patients with ALI/ARDS is multiple organ failure and irreversible respiratory failure, with 84% of deaths occurring more than three days after the onset of ALI/ARDS caused by multi-system organ failure (Ware and Matthay 2000).

Acute lung injury is a term used to describe the response of the lungs to a broad range of insults with ARDS representing the most severe end of the spectrum. Its pathophysiology is driven by an aggressive inflammatory reaction which results in widespread changes throughout the lung. A broad variety of precipitating causes are recognised and these can be differentiated into those which cause injury to the lung directly and those which cause injury indirectly (see Table 1.3). A number of endogenous anti-inflammatory mechanisms are also initiated to counteract the effects of the aggressive pro-inflammatory response; however, these responses may be excessive and contribute to a state of immunoparesis (Doyle et al. 1995).

Table 1.3 Risk factors for ARDS.

| Direct causes | Indirect causes |

- Aspiration of gastric contents

- Pneumonia

- Near drowning

- Lung trauma, e.g. blast injury, lung contusions

- Inhalation injury

- Fat emboli

| - Sepsis

- Massive blood transfusion

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Pancreatitis

- Cardiopulmonary bypass

- Pregnancy-related ARDS

|

Epidemiological literature indicates that the major risk factor for the development of ALI and ARDS is severe sepsis; 18–40% of patients with sepsis will develop ALI/ARDS, followed by pneumonia, aspiration of gastric contents, multiple blood transfusions, multiple trauma and pregnancy-related ALI/ARDS (Villar and Slutsky 1989; Ware and Matthay 2000).

From Mr Kuan Yew's clinical history and initial presentation it appears that he may have developed an acute lung injury and subsequent ARDS from a direct cause such as lobar pneumonia. It is also important, however, to note that as Mr Kuan Yew is mechanically ventilated and is critically ill, he is at a significant risk of developing a nosocomial infection and secondary sepsis (Vincent et al. 1995), a major risk factor for the development of ARDS, and at present he is indeed demonstrating signs of severe sepsis.

ALI and ARDS cause diffuse alveolar damage affecting all parts of the alveolus, including the epithelium, the endothelium and the interstitial space. It is a progressive condition with the pathological changes typically described as passing through three overlapping phases – an inflammatory or exudative phase, a proliferative phase and a fibrotic phase (Ware and Matthay 2000).

Exudative phase

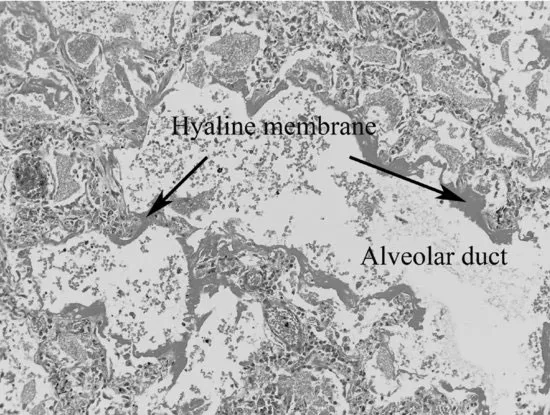

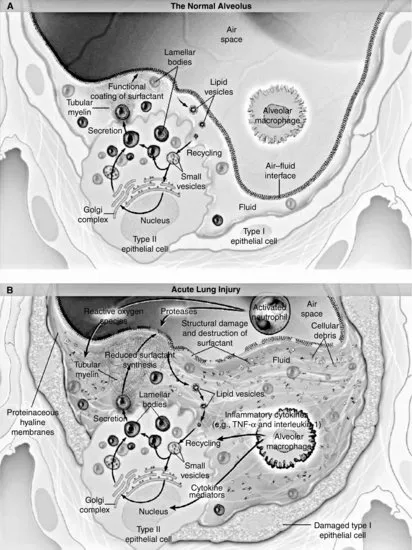

Lasting for up to seven days following the onset of symptoms, the exudative or acute phase of ALI/ARDS is characterised by the influx of protein-rich oedema fluid into the alveolar air spaces, as a result of increased permeability of the alveolar–capillary membrane and the formation of hyaline membranes. The hyaline membranes contain necrotic epithelial cells, plasma proteins which have been deposited in the alveolar space as part of the inflammatory exudate that leaks across the alveolar–capillary membrane, immunoglobulin and complement. The alveolar–capillary barrier has focal areas of damage and the alveolar wall is oedematous. Neutrophils are increasingly found within the capillaries, interstitium and eventually airspaces. As the process of damage progresses, there is extensive necrosis of type 1 alveolar epithelial cells and further hyaline membrane formation (Figures 1.2a and 1.2b).

These pathological changes can be seen in Mr Kuan Yew's clinical picture by the presence of pulmonary oedema and his deterioration in lung function. Flooding of the alveoli with protein-rich fluid and debris has caused a decrease in lung compliance, reflected in the high airway pressures. It has also caused a significant reduction in the diffusion of oxygen, leading to a reduced arterial oxygen saturation and PaO2. Fluid-filled and collapsed alveoli result in the development of a right to left intra-pulmonary shunt. The negative effects of this on Mr Kuan Yew's gas exchange are further compounded by loss of the normal compensatory hypoxic pulmonary constriction.

Proliferative phase

The proliferative phase is characterised by organisation of the hyaline membranes by proliferating fibroblasts, cell debris and inflammatory cells (Ware and Matthay 2000). Necrosis of type 1 alveolar cells exposes areas of the epithelial basement membrane and the lumens of the alveoli fill with leucocytes, red blood cells and fibrin. Type 2 alveolar cells, which are responsible for the production of surfactant, are also damaged but some proliferate along the alveolar wall in an attempt to cover damaged areas of the epithelium and differentiate into type 1 cells. Pulmonary oedema is less prominent at this stage; however, alveolar collapse becomes more marked and the alveolar ducts become narrowed and distorted. This then leads to a further increase in the degree of intrapulmonary shunt, leading to a further deterioration in gas exchange, and hypoxaemia resistant to oxygen therapy.

At this stage the process can be reversed and the lung parenchyma may return to normal. However, in some cases the damage is severe and the hyaline membranes become incorporated into the walls of the revised alveoli (Ware and Matthay 2000).

Fibrotic phase

The fibrotic phase can begin as early as ten days following the insult and is characterised by progressive thickening of the vasculature walls and an increase in the amount of lung collagen (Ware and Matthay 2000). Fibrosis results in a further reduction in lung compliance, increasing the work of breathing, decreasing the tidal volume and resulting in the retention of CO2. As a result of the destruction of some alveoli and interstitial thickening, gas exchange is reduced and this contributes to further hypoxaemia and ventilator dependence.

Pathogenesis of ALI/ARDS

Inflammation

As a result of the initiation of an inflammatory response, there is increased leucocyte production and mobilisation to the inflamed site. Mediator cascades including the production of cytokines, chemokines, free radicals and complement and coagulation pathway components are also activated. There is also an anti-inflammatory response.

The neutrophil is the dominant leucocyte involved in the pro-inflammatory response. Neutrophils cause cell damage by the production of free radicals, pro-inflammatory mediators and proteases, and excessive quantities of these products, including cytokines, have been found in patients with ARDS (Chollet et al. 1996). The inflammatory response is in part driven by cytokines. Two of the major pro-inflammatory cytokines are tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 (IL-1). The actions of these include (1) recruitment and localisatio...