![]()

PART ONE

THE SHATTERED COVENANT

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Forgotten Survivors

What Happens to Those

Who Are Left Behind

“No one is happy anymore. I think a lot of people are under stress, and it tends to balloon out, and everybody is absorbed by it. You don’t have anybody coming in in the morning, going, ‘God, it’s a great day!’”

Layoff survivor sickness begins with a deep sense of violation. It often ends with angry, sad, and depressed employees, consumed with their attempt to hold on to jobs that have become devoid of joy, spontaneity, and personal relevancy, and with the organization attempting to survive in a competitive global environment with a risk-averse, depressed workforce. This is no way to lead a life, no way to run an organization, and no way to perpetuate an economy.

The root cause is a historically based, but no longer valid, dependency relationship between employee and employer—a type of cultural lag from the post-World War II days when employees were considered long-term assets to be retained, nurtured, and developed over a career as opposed to short-term costs to be managed and, if possible, reduced. The first act of the harsh reality of this new psychological employment contract became painfully evident in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Then there was an intermission when both employees and employers were seduced back into complacency by the liquidity and economic boom of the early years of the new millennium. The curtain abruptly rose for act two with the financial meltdown of 2008, and we are now facing the jolting reality of a worldwide wake-up call. The second act is much more somber and represents the final shattering of the old psychological employment contract. We are caught up in an unprecedented global epidemic of layoffs, and the toxic effects of layoff survivor sickness on both individuals and organizations are approaching a pandemic tipping point.

The battle to ward off and eventually develop immunity to these survivor symptoms must be waged simultaneously by individuals and organizations. This battle is among the most important struggles that we and our organizations will ever face. Individuals must break the chains of their unhealthy, outdated organizational codependency and recapture their self-esteem; organizations must reconceptualize their paradigms of loyalty, motivation, and commitment in order to compete in the new global economy.

The old psychological employment contract began to unravel about twenty years ago, and some people are still feeling the effects. Although we are well into act two, the dynamics haven’t changed, and we can learn much from the past. For the organization, managing according to outdated values will no longer work. For individuals, struggling to hold on to a meaningless, deflated job can be a Faustian bargain that is hazardous to their mental health, as the following examples illustrate.

Lessons from Act One: Juanita and Charles—Victim and Survivor

When the layoffs hit, Juanita and Charles were both department directors, the lower end of the upper-management spectrum in the high-technology firm where they worked. Juanita was in her late forties, Charles in his early fifties. Although they had traversed very different paths to their management jobs, they were equally devastated when their organization started “taking out” managers to reduce costs. They experienced similar feelings of personal violation when the implicit psychological contract between each of them and their organization went up in smoke. Although this contract was only implied, Juanita and Charles had assumed that the organization shared their belief in the importance of this contract.

It wasn’t long before both were experiencing survivor symptoms of fear, anxiety, and mistrust.

Juanita had achieved her management role. She had returned to school in midcareer, earned an M.B.A, and—through talent, determination, and the efforts of a good mentor—moved quickly through Anglo-male management ranks that were lonely and uncharted for a woman. When Juanita lost her job, the official explanation was that her department was “eliminated” and no other “suitable” positions were available. In reality, she was done in by the existing old-boy network, which at least in the early stages of the layoffs looked after its own. (In a form of layoff poetic justice, the network fell apart as the “rightsizing” continued.) Juanita was a “layoff victim.”

Charles evolved into his management role. He was a classic organization man, joining the company right out of college and following the traditional career path of working his way up the system by punching the right tickets, knowing the right people, wearing the right clothes, and generally walking the walk and talking the talk. This career path was a hallmark of the large hierarchical public and private organizations that dominated the post-World War II era in North America, Western Europe, and Japan. The psychological contract that Charles and Juanita trusted was a legacy of this organizationally endorsed career path. Charles believed he had made a covenant that unless he violated the norms and standards of his company, he could count on his job until he retired or decided to leave.

Although Charles lost his influence, watched his support network disintegrate, ended up taking a substantial salary cut, and lived in a constant state of anxiety, guilt, and fear, he managed to hang on long enough to qualify for early retirement. He carried anger and depression with him when he left. Although technically a survivor, he is a victim of layoff survivor sickness. He would have been better off psychologically if he had left, and his company certainly would have been much wiser to invest in helping him make an external transition than living with his anger, guilt, and anxiety for fifteen years.

When Juanita was laid off, the company helped her take stock of her life and career. It spent some time and a fair amount of money on her psychological counseling and outplacement services. Juanita took over two years to grope her way through a time of exploration, regeneration, and ambiguity that William Bridges (1980) has called the “neutral zone.” She emerged as a principal in a small but vibrant and thriving consulting firm. She has cut back her hours somewhat in the past few years, but is still excited about life and stimulated by her work, and she has merged her career and personal life into a balance she found impossible in her previous job. She become a much more integrated and congruent person as a layoff victim.

Charles is still living an anxiety-ridden life. His guilt, fear, and anger have spilled outside the job. He is now divorced and emotionally isolated, and he continues to struggle with alcoholism. His company, which after twenty years and two mergers, is still mostly intact, is going through another round of layoffs. Once again, in act two, it is spending some of its very scarce recourses to help those who are leaving but doing nothing to re-recruit those who have survived. As a result, the legacy of Charles lives on in a whole building filled with angry, unproductive, risk-averse employees. This is the team the company is fielding to compete in a global marketplace where innovation and creativity are the only true competitive advantage.

The Basic Bind: Lean and Mean Leads to Sad and Angry

Layoffs are intended to reduce costs and promote an efficient lean-and-mean organization. However, what tends to result is a sad and angry organization, populated by depressed survivors. The basic bind is that the process of reducing staff to achieve increased efficiency and productivity often creates conditions that lead to the opposite result: an organization that is risk averse and less productive than it was in the past.

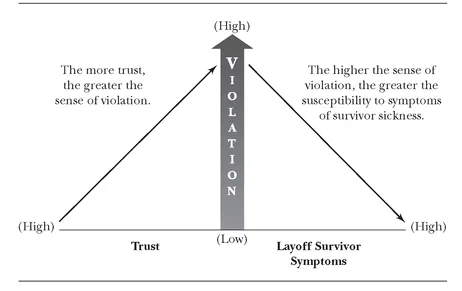

The key variable is the survivors’ sense of personal violation. The greater their perception of violation, the greater their susceptibility is to survivor sickness. The perception of violation appears directly related to the degree of trust employees have had that the organization will take care of them. Since nearly all organizations in the past had strategies of taking care of their employees, this basic bind is alive and well (Figure 1.1).

One symptom of layoff survivor sickness is a hierarchical denial pattern: the higher a person resides in an organization, the more he or she will be invested in denying the symptoms of the sickness. This is one of the reasons that managers are often reluctant to implement intervention strategies, despite the increasing evidence of an epidemic of survivor symptoms, despite entire organizations filled with people like Charles. Understanding and dealing with survivor symptoms requires personal vulnerability and an emotional and spiritual knowledge of the symptoms. Most top managers are excellent at playing the role they and their employees have colluded to give them. Their egos require that they present an image of cool control and that they appear skilled and comfortable with rational and analytical knowing rather than emotional knowing. The management job in a downsized organization is extremely complex and demanding.

Figure 1.1. The Basic Bind

Metaphor of the Surviving Children

Managers and organizational leaders play a vital role in bringing about the emotional release necessary to begin the survivors’ healing process after layoff. Their denial must be dealt with before there can be any release. In my experience, confronting denial head-on serves only to reinforce it. Methods that help people reach out to and legitimize their emotions and spiritual feelings are more useful in helping these people to understand the dynamics of their layoff survivor sickness. For example, I find that the metaphor of the surviving children is a compelling way to demonstrate the emotional context of survivor sickness to managers and help them move past denial:

Imagine a family: a father, a mother, and four children. The family has been together for a long time, living in a loving, nurturing, trusting environment. The parents take care of the children, who reciprocate by being good.

Every morning the family sits down to breakfast together, a ritual that functions as a bonding experience, somewhat akin to an organizational staff meeting. One morning, the children sense that something is wrong. The parents exchange furtive glances, appear nervous, and after a painful silence, the mother speaks. “Father and I have reviewed the family budget,” she says, looking down at her plate, avoiding eye contact, “and we just don’t have enough money to make ends meet!” She forces herself to look around the table and continues, “As much as we would like to, we just can’t afford to feed and clothe all four of you. After another silence, she points a finger: “You two must go!”

“It’s nothing personal,” explains the father as he passes out a sheet of paper to each of the children. “As you can see by the numbers in front of you, it’s simply an economic decision. We really have no choice.” He continues, forcing a smile, “We have arranged for your aunt and uncle to help you get settled, to aid in your transition.”

The next morning, the two remaining children are greeted by a table on which only four places have been set. Two chairs have been removed. All physical evidence of the other two children has vanished. The emotional evidence is suppressed and ignored. No one talks about the two who are no longer there. The parents emphasize to the two remaining children, the survivors, that they should be grateful, “since, after all, you’ve been allowed to remain in the family.” To show their gratitude, the remaining children will be expected to work harder on the family chores. The father explains that “the workload remains the same even though there are two fewer of you.” The mother reassures them that “this will make us a closer family!”

“Eat your breakfast, children,” entreats the father. “After all, food costs money!”

After telling this story, I ask surviving managers to reflect individually on the following five questions. Then I ask them to form small groups to discuss and amplify their answers:

1. What were the children who left feeling? Most managers say, “anger,” “hurt,” “fear,” “guilt,” and “sadness.”

2. What were the children who remained feeling? Most managers soon conclude that the children who remain have the same feelings as those who left. The managers also often report that the remaining children experience these feelings with more intensity than those who left.

3. What were the parents feeling? Although the managers sometimes struggle with this question, most of them discover that the parents feel the same emotions as the surviving children.

4. How different are these feelings from those of survivors in your organization? After honest reflection, many managers admit that there are striking and alarming similarities.

5. How productive is a workforce with these survivor feelings? Most managers conclude that such feelings are indeed a barrier to productivity. Some groups move into discussions about effects of survivor feelings on the quality of work life and share personal reflections.

What most managers take away from the metaphor of the children is a powerful and often personally felt understanding of the radical change the managers are experiencing in their own organizations. The vast majority of managers were hired into organizations that encouraged employees to feel part of a family in which the managers performed the benevolent parent role. The reward for such performance was that all organizational employees, from executives to production people, would be taken care of.

The harsh reality of the new psychological contract is that many “family” members are no longer cared for and are treated as dispensable commodities. It is not my intent to label this situation as good or bad. It is a sad situation for many, and the existing situation for everyone. The fact is that the old “family” contract is ending and the new competitive realities are creating a fundamental shift in the relationship of individual and organization. Managers and nonmanagers alike are part of this fundamental change in the system. It is how to respond to this change, how to make it good rather than bad, that I am concerned with here.

Acts One and Two: A Family Legacy

George was a casualty of an act one layoff. He was manager of production control coordination for the manufacturing division of a computer company. What that title actually meant was that he was highly skilled at managing an administrative system that was of value to only one company at one point in time. When he lost his job, he found himself with large mortgage payments, loans on two cars, quarterly payments for a country club membership, the prospect of twelve years of private school tuition payments for his first-grade daughter, Betsy, and no transferable skills. Like the metaphorical children who left the family, he too was a victim; he had trusted that if he did his job well, the organization would take care of him. When that didn’t happen, he went into an em...