![]()

PART ONE

White Space Revisited

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Silver Anniversary of Process

CIRCA 1985

In April 1985, we (Geary and Alan) were invited to make a presentation at the annual conference of the National Society of Performance & Instruction (NSPI)1 because somebody had told the society that we were doing some “experimental stuff ” at Motorola.

At the time Geary was founding partner of the consulting company, the Rummler Group, and Alan was a training manager and internal consultant for the Semiconductor Products business groups in the Phoenix area. Over the course of about two years, we had developed a new improvement methodology, and in late 1984 we got a chance to apply it to a business unit that was suffering from some significant delivery, product quality, and coordination problems. They were losing business to competitors. We got the senior management team to sit down and assess their way of managing the work flow. Most important, this team was composed of heads of several different business groups who had been asked to create and support this line of business but who had never acted as a coherent management team. It was during one of those work sessions that Rummler first posited the notion that the job of the team was “managing the white spaces on the organization chart.”

At the time we had no name for this new methodology. During the NSPI presentation we laughingly referred to it as “our thing,” like La Cosa Nostra, but we weren’t quite sure what we had—it had started as a training program, morphed into a kind of problem-solving approach, and ended as a management “team-building” intervention, for want of a better label. But while we had the methodology and tools worked out in a primitive way, we didn’t yet have any results to show.

Two months later, that changed. In June 1985, we reconvened the original team, now headed by a new senior executive, to see if any good had come out of the effort. It turned out that cycle time had been cut from fourteen weeks to seven weeks in nine months. The business—addressing a vital new segment for the sector—had turned completely around, and now the competition was chasing them.

That was the beginning. We had invented and then evolved the first systematic process design, improvement, and management methodology. Yes, we recognize that many other pioneers made great contributions to the field of what is now “business process management” (BPM)—among them, Frederick Taylor and W. Edwards Deming—long before us. But their ideas were adopted mostly by manufacturing companies, and process meant the production process. It was not until the 1980s that the business process movement—meaning design, improvement, and management of all important processes inside organizations—took hold, and that, in our view, was the beginning of BPM.

Our methodology was eventually employed in most of the major business units at Motorola, then was married to Motorola’s version of TQM and rolled out in the late 1980s as Six Sigma. By 1990, “our thing” had had a major impact on the transformation of Motorola from a company with quality problems to a world-class leader in innovation and continuous improvement. In 1990, A. William Wiggenhorn, founder of Motorola University and the man who had brought Rummler into Motorola, estimated that the impact of these improvement efforts came to $950 million in savings for what was a $10 billion company at the time. During our years there, revenues tripled.2

Along the way, we had both invented and proved the benefits of an improvement methodology that yielded tangible business results with often startling speed. By the late 1980s, the methodology was being endorsed by the CEO on down, and Geary, as a member of the Motorola Management Institute from 1984 to 1995, taught the key concepts and approach to a generation of senior to midlevel managers.

Not that the path to success was always swift and smooth. At first we did not know how to describe this new approach to improvement nor how to educate clients on the importance of processes. The most receptive areas at first were in manufacturing, where TQM was practiced and the concept of process was familiar (although everyone meant the manufacturing process only, not the larger business processes); outside of manufacturing, the notion of process was entirely foreign. Gradually, though, we learned to articulate the benefits of a process view, and we gained adherents one by one.

During that period, Motorola was the most fertile ground for this pioneering work, but there were other takers. Geary built out the methodology as he also did work with other large corporations, including Ford, GTE, Douglas Aircraft, GM, GE Plastics, Sherwin-Williams, Ryder Truck, Capital Holding Corporation, Hillenbrand Industries, Sematec, and VLSI.

Characteristics of the Approach

What made the methodology work so well? There were several characteristics of these early projects that we think made all the difference:

1. Our process improvement projects at Motorola were conducted directly with the senior executives of the business units where we operated. Instead of having intermediary teams of specialists and lower-level managers on “design teams,” the executives functioned as both “process owners” and designers in what we called an Executive Process Improvement Project. That is one reason why results were often achieved so quickly. Instead of months of analysis, process modeling, and commitment building with midlevel executives and other stakeholders, the people with the power to make things happen were the ones who had designed the improvements and wanted them implemented post haste. There was little time needed to create consensus and seldom much resistance. These people had competitive pressures and were serious. (We note that when we went to other companies, we ended up creating design and steering teams because the Executive Process Improvement Project was a hard sell.)

2. The focus of the improvement projects was on critical business issues such as total customer satisfaction, value creation, and growth of the business. These were issues that executives cared most about and would put their energies into addressing. We didn’t do “process work” merely because it seemed like a good thing to do; we did it only in service of a burning business issue.

3. Because of the focus on critical business issues, the processes that we helped to redesign tended to be the core, value-adding processes that create and deliver products and services right to customers. We were not buried in “enabling processes,” although we often dealt with them in order to make them more effective in serving the core processes.

Assumptions on Which We Built the Approach

The process improvement methodology that started at Motorola went through innumerable upgrades throughout the 1980s and 1990s as we, with our clients, learned more and more about process design, discovered additional tools and techniques, and covered greater ground in the quest to make it a comprehensive approach for change. In the early years, for example, there was no material on implementation. We relied on our clients to install their redesigned processes, and many did so, but some stumbled hardest at the point when the design work was complete but the organization at large had not accepted it. We added an additional phase to deal with implementation and change management.

There were, however, some basic assumptions about processes and organizations that were used in developing and applying the methodology, and they have proved to be true over the decades.

1. Organizations as Systems

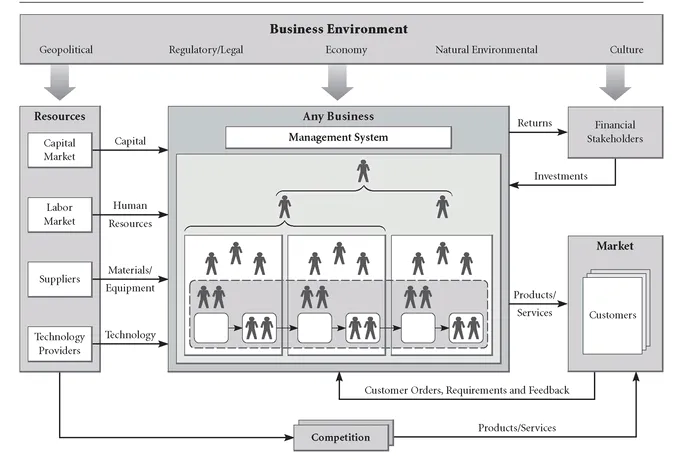

We believe that every organization, public or private, is a system of interdependent parts and is subject to systems logic. The concept of systems applies at any level of a given organization, whether it’s an entire enterprise existing within a larger, super-system of market, environmental, and competitive forces, or a business unit or even a single department, existing inside as a system within systems. Figure 1.1 is a diagram of any business organization sitting inside its super-system.

Figure 1.1 The Organization as a System

There are several corollaries to this assumption:

• Every organization is a gigantic processing system, composed of inputs, outputs, and internal processes that transform the inputs into valued outputs. Therefore, every process exists as part of a network of interdependent processes, each playing a role to produce value, manage the production of value, or support that transformative work. This means, among other things, that a single process cannot be effectively redesigned without a clear understanding of the other processes to which it is connected and to the organizational system of which it is only a part. And often, in order to address the deficiencies of a given process, we had not only to understand the larger system in which it resided, but to make improvements in the larger system.

• Every organization must be an adaptive system, continually monitoring the larger super-system and making small and large adjustments to be successful or even to survive in the long run. The critical business issues that were addressed by our process improvement projects at Motorola and other companies were all traceable to something in the super-system and the need for adaptiveness. The issue might be customer dissatisfaction with delivery times, poor product quality, the need to grow a market segment—the critical business issues were always an expression of the company’s need to be more responsive to some changing condition or its own wish to change the competitive landscape.

2. Processes Are About Work

Process work is all about defining and managing work. The notion of “process” has turned out to be the best way to articulate the work done in organizations, and that is why it has outlasted its days as a management fad and now is a generally accepted concept for understanding and designing organizations.

3. Three Levels of Performance

In order to achieve sustained high performance, an organization has to plan, design, and manage performance at three levels: organization, process, and job. We focused on process improvement because we knew that processes (being all about the work) had the greatest leverage for change, yet they were the least understood, defined, or managed. But the implication of this assumption is that even though our process improvement work was aimed at the middle level, we well understood that process improvements had to be linked upward to organizational goals, plans, and structure, and downward to the daily activities performed by individual performers.

MILESTONES SINCE 1990

Since 1990, process has followed a trajectory that took us by surprise. In the 1980s, our heads were mostly down, doing this kind of work in a few companies because we saw the results yielded and we were persona...