![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Spotting Project Fog

The last five years of my professional life involved completing a doctorate in project management (DPM) and exploring strategic issues related to the practice of project management in organizations. The research conducted for my thesis is the genesis of this book. As I traveled the world of project management and C-suite executives that are so critical to the process of sponsoring and executing projects, I began to recognize that both parties were frustrated with the efforts and results from the other.

Project management professionals often feel distant and unconnected to the strategic management processes of their organizations. Rather than being strategic partners, they feel like a pair of hands that kick into action once a project has been selected and approved for implementation. Yet they could contribute so much more to the process if they were involved from the outset in the definition and selection of projects and worked closely with the executive team to help them realize their strategic vision. Since projects are often the building blocks of strategy execution, something that all executives should be focused on, it would seem like a natural partnership. Project managers want to ensure that their hard work matters and that what they are doing is truly strategic. Yet in my surveys, many project managers worldwide report feeling like they work on a never-ending list of projects with doubtful intentions and lack a clear strategic focus. They rarely feel connected to their executive sponsors or feel that they are on a strategic mission together towards a defined destination. This feeling of drift is not healthy for any professional. Its origins need to be examined so that organizations can address their level of motivation and engagement.

Over the past twenty years there has been an unprecedented level of investment in project management, as more of the work of most organizations comes in the form of projects. Accordingly, executives have stepped up and approved investments in new resources in a wide variety of ways.

This can mean funding additional dedicated PM positions or functions, such as a project management office or center of excellence. Some organizations buy, and some build, standardized project management methodologies to support consistent project management practices internally. Others have invested in online tools and other forms of automation to support PM processes in the belief that project management practices, properly implemented and executed, improve productivity and returns. However, the reality for many CEOs that I talk to is that they are not always seeing these returns clearly. In fact, there are almost as many published studies about how many strategic projects fail at huge cost to their organizations as there are articles about the success of project management practices in organizations. So all this leads to valid concerns about the value of all these PM-related investments and just exactly what the benefits are. What is really going on? I believe the answer lies in the presence in most organizations of project fog.

Project fog happens when we have so many things we call projects (or initiatives, or programs), picked from an even larger list of potential concepts, approved or not over the space of many years, and now overlapping to the point where the many potential business benefits may or may not still be valuable. We lose track. We get lost. Like real fog, project fog creeps up on us and overtakes us almost unaware and before we know it, it’s too late to avoid it because we’re in it.

Oddly, most of the organizations that I studied do not actually have a “project management problem” per se, even when they report feeling like they are in a project fog. In fact, most organizations have become pretty good at executing single and multiple projects; this is not where the problem lies. So my research focused on identifying the real underlying problem and trying to understand why executives and project managers feel the way they do.

As I determined from various case studies, the origins of project fog occur well before an organization begins to execute projects, and instead relates to how projects are proposed and selected. In project management terms, this is referred to as project portfolio management (PPM)—an emerging buzzword in the profession today. However, while there is substantial discussion about this important aspect of project management, little that is definitive has been written about how to do it well, and this is both the source of and solution to the project fog. If we learn to manage the ways we propose and select projects as well as we know how to execute them, the project fog will clear up and your organization’s strategic potential will improve. So let’s begin.

HOW THE FOG ROLLS IN

Spotting a portfolio management process problem among my clients often begins with a simple complaint: “We have too many projects and project proposals!” (This is the salient symptom of being in the fog for most organizations.) How is it, I wondered, that these organizations were selecting and then approving so many of the same strategic projects they were now complaining about in the first place?

As I discovered during research interviews, there were in effect so many forms of effort inside most organizations called a project—a program, initiative, pilot, campaign, product launch or a host of other names—that losing track of them was easy! The senior executive team obviously must think they are all “strategic” or they wouldn’t be approving them, and project managers must have been consulted on the plans for them. So then who exactly is responsible for an organization having “too many projects”? Those actually proposing them or those ultimately approving them? The answer, it turns out, is both. I began to refer to this in my consulting work as “project fog,” and the term seemed to really resonate.

This also led to three simple questions that I pose to organizations I work with to help them determine if they might be in the fog. These questions are:

1. Are you planning the most strategic projects possible, and how do you know that as an executive team member or project manager?

2. What if the most strategic projects are not being conceived and proposed because your project selection criteria mostly encourage projects that are financially efficient versus strategically effective?

3. And what do you do if your organization’s primary purpose cannot be measured in terms of profitability? How do you measure strategic contribution and connect this to project selection?

Using these questions, I began to notice that the portfolio project management approaches that organizations were using to try and manage all of this effort seemed inadequate to address the true complexities of enterprise-wide project selection and management. In fact, if they had a systematic approach to project selection at all, it seemed to be one that validated simply having lots of projects!

Too many projects were getting approved, and for all the wrong reasons. And then they were not managed cohesively for maximum strategic benefit. All approved projects were chasing the same limited resources available to do all the project work, so some were bound to fail. Project chaos was exhausting everyone. It became clear to me that new strategic project portfolio management practices were needed.

I realized that, for all of the effort to professionalize project management, maybe we had missed a strategic underpinning of huge potential value: what if we were actually expending all this effort to execute projects that were potentially not very strategic? And what did this mean for the profession? Could avoidance of defining solutions to this problem be a lapse in professional responsibilities? Similarly, as executives or board members, what could you contribute to solving this problem and encouraging a level of partnership with project management professionals that would focus on strategy execution rather than purely on project execution?

To clarify the extent of the problem, my initial research efforts focused on a few large corporations. What became immediately obvious was that their business objectives were normally related to enhancing profits. In and of itself, this is not a surprising objective, nor would most shareholders say this is inappropriate for a private sector firm. But when I looked more deeply into this challenge, it became instantly clear that if an organization’s effort at project scoring, a critical aspect of picking and prioritizing projects, was based exclusively on financial efficiency, it was then sub-optimizing strategic outcomes. Why? Because the most strategic projects were unlikely to always generate the highest return. Ask any CEO and he or she will tell you honestly that innovation and creativity cost money—and that is exactly what strategic projects are all about. They are vital to long-term health but may actually cost us in the short term. (So while you can probably agree with this statement, I expect that your project selection system today likely defeats this outcome by focusing on the selection of projects with high financial returns.)

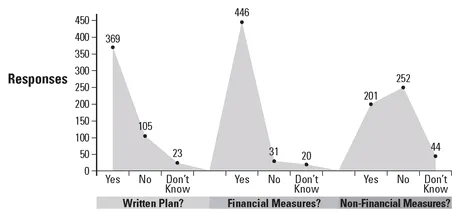

This was intriguing on another front, because almost all of the organizations I studied had complex, written strategic plans, and a review of most of these would reveal fairly complex underlying business acumen. Yet few of them had non-financial measures as part of their project selection criteria, as seen in the graph below.

Planning & Measuring Paradigms

The shape of this graph is important, for it gives visual representation to data that underlie an important trend. The shape of the first area of the graph (on the left side) shows 74% of respondents (369 out of 497) had written plans and the second part of the graph (moving towards the right) indicates a whopping 90% had financial measures associated with those same plans. Yet we see quite a different story when it comes to the use of non-financial measures in the last graph. Here there are both more diffuse levels of usage and a much higher number who simply responded that they “didn’t know.” This began to suggest that the measures being used to track strategic success were perhaps less robust than the underlying strategic plans they were attempting to support. As we will see in the later case studies, this was exactly the case.

So the consequence of this relatively naïve approach to project selection is that if an organization uses only financially based metrics to pick their projects (the case for the majority of our survey respondents), this can lead to a false belief that they are making the right decisions and selecting the right projects—when the opposite is probably true. As you will see, in the long term these organizations would be losing opportunity (and the associated profits!) when you consider the results across their entire project portfolio. Was it possible this was happening because they were unaware of this loss, or were they simply unwilling to do the harder work of figuring out what was truly strategic?

Another perplexing finding was that almost all of the existing PPM methods that I saw were focused on how to rank and select new projects, yet they paid little attention to shifting the priorities of (or canceling) existing projects. This gives rise to a “portfolio within a portfolio” approach, where the project selection method does not operate on the entire portfolio at one time, but on a sub-set. Regardless of what sub-set we define (buckets by project type; separating new projects from existing ones; or using definitions of strategic complexity, such as platform versus operational projects), the point of managing the entire portfolio as one is lost. An additional layer of financial and resource inefficiency has now entered the picture. Just eliminating some of the redundant work done on projects that should be canceled in favor of new initiatives can significantly improve project costs and resource utilization. Yet few seem to be concerned about this. Most project managers I spoke with during my research reported that organizational priorities were often on new projects rather than on the status or progress of existing ones.

When this same practice of false economies is translated into the more complex strategy-making context of a public sector or not-for-profit organization, it becomes even more inappropriate as a project selection method. In fact, it might even be considered criminal or at least unethical as a recommended practice in that context. The problem arises from an underlying assumption that projects which maximize financial return and minimize risk are the most strategic projects to select. This premise can have unintended or even disastrous consequences and numerous examples could be cited in most countries of the world of this very phenomenon. For both types of organizations, little seems to have been written to date that can help guide the definition and selection of “strategic projects,” making the application of portfolio management tools hard to achieve in practice for just about any organization of any type.

Now let’s thicken the fog slightly: when I directly explored the current use of PPM techniques among experienced project managers and executives, there was a decidedly negative response. Most either didn’t know too much about it or reported generally lower use of this technique than project/program management and project management offices (PMOs). There was a sense, later confirmed in detailed interviews, that most of the approaches in use today were seen as too complex for the limited benefits they seemed to deliver once implemented. This hypothesis was further confirmed by an early pilot study conducted among experienced PMs who clearly shared this view.

So this is not simply a matter of lack of experience with methodologies or techniques that some were not aware of; rather, it now seems like a genuine gap in professional practice. This means that without substantial improvements, most organizations will not choose to use portfolio management techniques as they exist today. And those hardy few who do risk a failed implementation. They only frustrate their organizations’ executives, project managers, and project staff. Not such a good outcome, for a profession supposedly on the rise. So . . .

The benefit of solving this problem would be high for organizations, and would be immediately evident to most executives—who would welcome the resulting clear focus on strategy execution. The trick that remains is to solve the problem and help organizations pick the most strategic projects for execution.

THE FOG THICKENS

This book is based on an extensive multi-year study of project managers and executive sponsors. The executives were working in a range of organizations, varying in scope and complexity, including financial services, insurance, information technology, transportation, manufacturing and industrial services. There were also respondents from government and the not-for-profit sectors. Given the hyper-competitive nature of the global economy today, all of these executives reported an urgent need to exponentially enhance organizational performance by improving the alignment between senior executives’ strategic goals and project managers’ efforts. Nobody has any time to waste and everyone is trying to move ever more quickly. To make this work requires a partnership around co-execution of strategy. It takes integration and mutual support.

On the other hand, project managers are worried about becoming mired in the “strategic muck” and unable to escape involvement in aspects of organizational strategy that they may or may not understand, and for which they do not feel responsible. They report that executives say they want to be strategic, but their behavior sometimes indicates otherwise. Some might actually prefer to operate in a strategically ambiguous place, where nobody can actually determine whether or not they really are as smart and accomplished as they seem. The problem demands action from both sides.

So how can we strengthen the link between project selection methods (primarily the domain of project...