- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Equine Exercise Physiology

About this book

Equine exercise physiology is an area that has been subject to major scientific advances over the last 30 years, largely due to the increased availability of high-speed treadmills and techniques for recording physiological function during exercise. Despite the scientific advances, many riders and trainers are still using little more than experience and intuition to train their horses.

The aim of this book is to sort the fact from the fiction for the benefit of those involved in training, managing or working with horses, and to provide an up-to-date summary of the state of play in equine exercise physiology. Scientific theories are explained from first principles, with the assumption that the reader has no previous scientific background. The book is designed to save competitors and trainers a lot of time and effort trying to extract information in piecemeal fashion from a host of reference sources. For the first time, everything you need to know about exercising and training horses is here in one text.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

The Raw Materials

Chapter 1

Introduction

Why train?

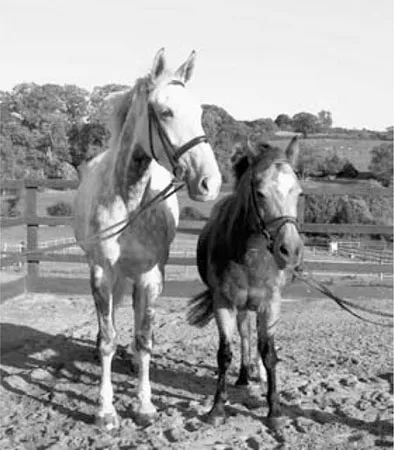

In theory and in practice, the horse must surely be considered the best all round athlete of the animal kingdom. Horses are not great thinkers or fighters, they are runners. Whatever the breed or type of horse, they are all blessed with the same basic structure and the same basic physiological mechanisms; therefore they all have the potential to respond favourably to training. A horse’s performance, i.e. how fast it runs, how high it jumps, is largely determined by its natural ability, and to a lesser extent by its level of training. Natural ability is determined mainly by the genes the horse inherits from its parents (Fig. 1.1). We can’t do anything about the genes an individual horse has once it has been born, but we can do something about the training. To reach a horse’s genetic potential for performance, whether it is aimed at local riding club events or the Derby, it must be fit! From the unfit to fit state the horse undergoes a metamorphosis and its shape, its gaits, its looks, often even its attitude to life, are altered. Whatever we strive to achieve with our horses, there is much to be gained by making sure that they are fit enough for the task. To compete on an unfit horse puts both you and your horse at risk, quite apart from decreasing your chances of success and also the likelihood of the two of you going on to compete year after year.

Horses are always huge investments in terms of both time and money. If you aim to compete at any level, it pays to improve the horse’s chances of completing the work goals without risking mechanical breakdown and so incurring large veterinary bills, long periods of rehabilitation at best and destruction at worst. There is no doubt that training is an art, but a little understanding of the physiology of the horse can help anyone perfect their own art. Much of what we currently understand about equine exercise physiology has been established in the last 20 to 30 years, largely as a result of an increased scientific and veterinary interest in exercise physiology, improvements in technology, and availability of equipment such as high speed treadmills. High speed treadmills enable vets and scientists to study the horse in controlled situations where the speed, distance, slope, going and environmental conditions can all be closely regulated. In addition, with a horse exercising on a treadmill it is a very simple matter to collect a blood sample from a catheter in an artery or vein, or to measure how much oxygen the horse is using. Procedures such as these are either difficult or at present not possible to undertake in the field. Inevitably, running on treadmills is not the same as running round a racetrack or a cross-country course, but it has enabled scientists to make great advances in the study of the horse’s responses to exercise and training. Many of these advances can now easily be applied to the management and training programmes of our own competition horses with a good degree of success. Whilst science cannot guarantee a winner, it may well shorten the odds in our favour.

What are the aims of a training programme?

What exactly are we trying to achieve as a result of training? The fundamental purposes of any training programme are to:

(1) Increase the horse’s exercise capacity

(2) Increase the time to the onset of fatigue

(3) Improve overall performance, by increasing:

— Skill

— Strength

— Speed

— Endurance

or all four of these

(4) Decrease the risk of injury.

Fig. 1.1 A horse’s performance is largely determined by the genes the horse inherits from its parents.

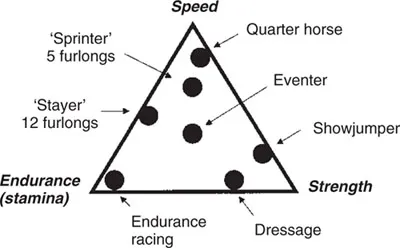

By analysing the adaptations the horse makes in the short term (during exercise) and in the long term (throughout training) we can begin to understand how to design the horse’s work programme to achieve these aims (Fig. 1.2).

Exercise, work, training, fitness and performance

First of all, let’s tackle the vocabulary of ‘exercise physiology’. Being associated with horses entitles you to become a member of a club that has its own language, a language which is only understood by those ‘in the know’. Consider some of our expressions: we talk about grey when we mean white; we ‘break’ horses when we are introducing them to being ridden; a three-day event can be held over 4 days. What chance do outsiders have? Scientists also have their own language, one that is universal amongst all sorts of them, such as biochemists, geneticists, physiologists, etc. To be able to translate the results of scientific studies and apply them to real-life training situations we need to become familiar with the scientific vocabulary associated with equine exercise physiology.

Fig. 1.2 Requirements for speed, strength and endurance in a range of equestrian sports.

Physiology is the study of the function of cells, tissues, organs and whole systems. Exercise physiology is thus the study of all systems involved in exercise. Exercise is a good example of a word commonly used in completely different contexts by scientists and horse people. Horse people often differentiate between lungeing a horse either for exercise or for work. The horse person’s interpretation of this is that by lungeing for exercise you are merely allowing the horse to ‘stretch its legs’ on the end of the lunge line, but it is not asked to do anything too taxing. Lungeing a horse for work means that it would probably wear side reins or maybe a ‘gadget’, e.g. a pessoa, and would be asked to engage its hindquarters and carry itself in a correct outline. To a scientist, work refers to the energy used up when an object moves a known or fixed distance; the amount of work done is described in terms of the energy used and is commonly measured in units such as joules (J) or kilojoules (kJ), or calories (cal) or kilocalories (kcal). A force has to be applied in order to perform work, and this force requires energy to be expended. Therefore the horse is doing work simply by moving from A to B. In scientific circles, ‘work’ does not infer anything about the quality of the movement (i.e. speed, distance or direction), simply that something has moved. In fact, in strict scientific terms, it takes the same amount of energy to move a horse from A to B at a walk as it does at the gallop: the difference is in the rate at which energy is used. The same amount of energy is required to move from A to B, regardless of the speed, but when the horse moves at the gallop, the rate of energy utilisation must be greater. The rate of energy usage is referred to in terms of power. Power is measured in terms of the rate of work done (units of energy per unit time), e.g. in joules per second or watts. In galloping from A to B, the horse must generate more power than if he walks from A to B. Exercise refers to any movement or activity, so as soon as the horse moves off from a standstill, it is performing exercise. To use our scientific terms, if the horse is exercising, work is being done.

Training is another term that may have different interpretations depending upon the context in which it is used. To horse people, ‘training’ often implies that the horse is learning: its ‘basic training’ is its basic education. To an exercise physiologist, training is a long-term process of repeated bouts of exercise, which results in an improvement in fitness, where fitness refers to a certain capacity for exercise. Training for improvement in fitness is sometimes also referred to as ‘conditioning’, particularly in the USA.

Throughout exercise and training, the horse’s body should make certain physiological adjustments, adaptations or responses. An exercise response is any short-term physiological adaptation that is made as a result of an increase in the level of muscular activity, whilst a training response is a long-term physiological adaptation to repeated bouts of increased muscular activity. Exercise responses tend to return to baseline levels after the work is done. For example, during exercise there is an increase in heart rate, corresponding to the intensity of the work done. When the horse stops exercising, the heart rate will gradually return to resting levels. Training responses are more long lasting and are maintained as long as the horse continues to regularly undertake a certain volume of work. For example, a training response may be an increase in heart mass (weight) or an increase in the number of capillaries (small blood vessels) around each muscle fibre. Changes such as these occur over a period of time as the horse responds to a gradual increase in workload, but they do not change throughout the course of an exercise bout. Training changes are mainly mediated through activation of genes that may then ‘code’ for greater production of an enzyme in an aerobic energy pathway, for example.

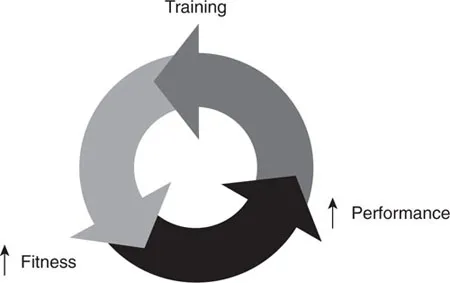

Fig. 1.3 Training leads to an increase in fitness and an improvement in performance.

The type of work undertaken is particularly important in determining whether or not a training response is induced. For example, walking a horse 16 km (10 miles) a day, 3 days a week for a month may produce a noticeable loss of body mass (bodyweight) as the horse will be using up a considerable amount of energy on each of these walks. However, it may do very little in terms of increasing fitness, i.e. producing a training response. When we think about training it is therefore not simply how much energy we use, i.e. the volume of work, that counts but the way in which that work is done, i.e. the quality of work, to induce appropriate training responses.

In summary, if we want to improve our horse’s performance, we would do well to increase their fitness (Fig. 1.3). This can be done by carrying out regular exercise, of progressively increasing workloads, to bring about the necessary training responses. The key is knowing what is the right work for what sport and when to settle for less than 100% fitness to reduce the risk of injury that might come from training very hard for a long time.

KEY POINTS

- Horses are natural athletes.

- Probably the biggest impact we can have on how well a horse performs is through training.

- The aims of training are to increase the time to the onset of fatigue, improve performance and decrease the risk of injury.

- Physiology is the study of the function of cells, tissues, organs or whole systems.

- Exercise means that work is done and so by definition energy is used.

- Exercise responses, e.g. an increase in heart rate, are short term.

- Training is a longer process of many repeated bouts of exercise that brings about an increase in fitness.

- Training responses, e.g. an increase in heart size, occur over a relatively long period of time.

Chapter 2

Energetics of exercise

Introduction

A little knowledge of biochemistry is a powerful thing! When you first become aware of the cellular processes involved in the conversion of nutrients into mechanical energy for muscle contraction it is like an enormous penny dropping, making so much of what the nutritionists tell us fall into place. For performance horses, one of the most important considerations is the energy content of the diet. To make sure our horse has enough energy for exercise, it helps to understand something about the way the horse’s muscles obtain energy from nutrients within the diet, and this forms the basis of the study of the energetics of exercise. Awareness of the energetics of exercise can help us formulate a diet to achieve a specific result. As far as interpretation of energetics is concerned, the horse is not dissimilar to ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Part I: The Raw Materials

- Part II: Exercise and Training Responses

- Part III: Applications of Exercise Physiology

- References

- Further Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Equine Exercise Physiology by David Marlin,Kathryn J. Nankervis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Equine Veterinary Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.