![]()

PART One

The Investing Environment

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Why Analyze a Security?

This chapter covers the origin and evolution of security analysis, which focused initially on publicly traded stocks and bonds. The herd psychology and gamesmanship that are endemic to the capital markets are discussed, along with modern valuation approaches.

Some investors analyze securities to reduce the risk and the gambling aspects of investing. They need the confidence supplied by their own work. Other investors seek value where others haven’t looked. They’re on a treasure hunt. Still others have fiduciary reasons. Without documentation to justify an investment decision, clients can sue them for malpractice should investment performance waver. Many investors analyze shares for the thrill of the game. They enjoy pitting their investment acumen against other professionals.

Security analysis is a field of study that attempts to evaluate businesses and their securities in a rational way. By performing a rigorous analysis of the factors affecting a company’s worth, security analysts seek to find equities that present a good value relative to other investments. In doing such work, professional analysts refute the efficient market theory, which suggests that a monkey throwing darts at the Wall Street Journal will, over time, have a performance record equal to the most experienced money manager. In fact, the proliferation of business valuation techniques as well as advances in regulation and information flow contributes to the market’s transparency. Nevertheless, on a regular basis, pricing inefficiencies occur. An astute observer takes advantage of the discrepancies.

THE ORIGINS OF SECURITY ANALYSIS

Benjamin Graham and David Dodd made the business of analyzing investments into a profession. With the publication of their book, Security Analysis, in 1934, they offered investors a logical and systematic way in which to evaluate the many securities competing for their investment dollars and their process was eventually copied by M&A, private equity, and other business valuation professionals. Before then, methodical and reasoned analysis was in short supply on Wall Street. The public markets were dominated by speculation. Stocks were frequently purchased on the basis of hype and rumor, with little business justification. Even when the company in question was a solid operation with a consistent track record, participants failed to apply quantitative measures to their purchases. Procter & Gamble was a good company whether its stock was trading at 10 times or 30 times earnings, but was it a good investment at 30 times earnings, relative to other equities? Investors lacked the skills to answer this question. Security Analysis endeavored to provide these skills.

The systematic analysis in place at the time tended to be centered in bond rating agencies and legal appraisals. Moody’s Investors Service and Standard & Poor’s started assigning credit ratings to bonds in the early 1900s. The two agencies based their ratings almost entirely on the bond’s collateral protection and the issuer’s historical track record; they gave short shrift to qualitative indicators such as the issuer’s future prospects and management depth. In a bond market dominated by railroad and utility bonds, the rating agencies’ methodology lacked transferability to other industries and the equity markets. On the equity side, in-depth evaluations of corporate shares were found primarily in legal appraisals, typically required for estate tax calculations, complicated reorganization plans, and contested takeover bids. Like credit ratings, the equity appraisals suffered from an overdependence on historical data at the expense of a careful consideration of future prospects.

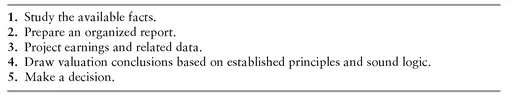

Graham and Dodd suggested that certain common stocks were prudent investments, if investors took the time to analyze them properly (see Exhibit 1.1). Many finance professors and businesspeople were surprised at this notion, thinking the two academics were brave to make such a recommendation. Only five years earlier, the stock market had suffered a terrible crash, signaling the beginning of a wrenching economic depression causing massive business failures and huge job losses.

The market drop of 1929-1933 outpaced the 2007-2009 crash. On October 28, 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 13 percent and an additional 12 percent the next day. The two-day drop of 23 percent followed a decline that began on September 3, when the Industrial Average peaked at 381, and then declined 22 percent in the weeks preceding October 28. The market staged modest recoveries in 1930 and 1931, but the 1929 drop presaged a gut-wrenching descent in stock prices, which wasn’t complete until February 1933. Over the three-year period, the Dow dropped by 87 percent. The index didn’t return to its 1929 high until 1954, 25 years later. In contrast, the Dow’s sizeable decline from 2007 to 2009 was 54 percent, and the 1999-2002 bear market represented a 34 percent drop.

At the time of the publication of Security Analysis, equity prices had doubled from 1933’s terrible bottom, but they were only one-quarter of the 1929 high. Shaken by the volatile performance of equities, the public considered equity investment quite speculative. Not only was there a dearth of conservative analysis, but the market was still afflicted with unregulated insider trading, unethical sales pitches, and unscrupulous brokers. For two professionals to step into this area with a scholarly approach was radical indeed.

EXHIBIT 1.1 Graham and Dodd Approach to Stock Selection

The publication of Security Analysis coincided with the formation of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Designed to prevent a repeat of the 1920s abuses, the SEC was given broad regulatory powers over a wide range of market activities. It required security issuers to disclose all material information and to provide regular public earnings reports. This new information provided a major impetus to the security analysis profession. Previously, issuers were cavalier about what information they provided to the public. Analysts, as a result, operated from half-truths and incomplete data. With the regulators’ charge of full disclosure for publicly traded corporations, practitioners had access to more raw material than ever before. Added to this company-specific data was the usual storehouse of economic, market, and industry material available for study. It soon became clear that a successful analyst needed to allocate his time and resources efficiently among sources of information to produce the best results.

NO PROFIT GUARANTEE

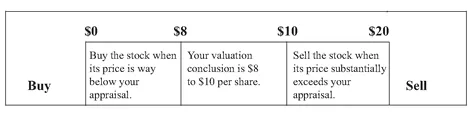

It is important to remember that security analysis doesn’t presume an absolute value for a given security, nor does it guarantee the investor a profit. After undertaking the effort to study a stock, an analyst derives a range of value, since the many variables involved reduce the element of certainty. After an investigation, assume the analyst concludes that Random Corp. shares are worth $8 to $10 per share. This conclusion isn’t worth much if the stock is trading at $9, but it is certainly valuable if the stock is trading at $4, far below the range, or at $20, which is far above. In such cases, the difference between the conclusion and the market prompts an investment decision, either buy or sell (see Exhibit 1.2).

If the analyst acts on his conclusion and buys Random Corp. stock at $4 per share, he has no assurance that the price will reach the $8 to $10 range. The broad market might decline without warning or Random Corp. might suffer an unexpected business setback. These variables can restrict the stock from reaching appraised value. Over time, however, the analyst believes that betting on such large differences provides superior investment results.

EXHIBIT 1.2 Random Corp. Stock

DAY-TO-DAY TRADING AND SECURITY ANALYSIS

For the most part, participants in the stock market behave rationally. Day-to-day trading in most stocks causes few major price changes, and those large interday differentials can usually be explained by the introduction of new information. A lot of small price discrepancies are attributable to a few professionals having a somewhat different interpretation of the same set of facts available to others. This results in one investor believing a stock’s price will change due either to (1) the market conforming to his opinion of the stock’s value over time, or (2) the future of the underlying business unfolding as he anticipates.

In the first instance, perhaps the investor’s research uncovered a hidden real estate value on the company’s balance sheet. The general public is unaware of this fact. As soon as others acknowledge the extra value, the stock price should increase. In the second situation, the investor has more optimistic growth assumptions than the market. Should the investor’s predictions come true, the stock price should increase accordingly. Perhaps 300,000 individuals follow the markets full-time, so there are plenty of differing views. Even a small segment of investors with conflicting opinions can cause significant trading activity in a stock.

It is not unusual that investors using similar methods of analysis come up with valuations that differ by 10 to 15 percent. This small percentage is sufficiently large to cause active trading. As we discuss later, the popular valuation techniques require a certain amount of judgment with respect to sifting information and applying quantitative analysis, so reasonable people can easily derive slightly dissimilar values for the same stock. As these differences become more profound, the price of a given stock becomes more volatile, and divergent valuations do battle in the marketplace. Today, this price volatility is evident in many high-tech stocks. The prospects of the underlying businesses are hard to appraise, even for experienced professionals.

HERD PSYCHOLOGY AND SECURITY ANALYSIS

Ideally, a security analyst studies the known facts of a business, considers its prospects, and prepares a careful evaluation. From this effort a buy or sell recommendation is derived for the company’s shares. This valuation model, while intrinsically sensible, understates the need to temper a rational study with due regard for the vagaries of the stock market.

At any given time, the price behavior of certain individual stocks and selected market sectors is governed by forces that defy a studied analysis. Key elements influencing equity values in these instances may be the emotions of the investors themselves. Market participants are human beings, after all, and are subject to the same impulses as anyone. Various emotions affect the investor’s decision-making process, but two sentiments have the most lasting impact: fear and greed. Investors in general are scared of losing money, and all are anxious to make more profits. These feelings become accentuated in the professional investor community, whose members are caught up in the treadmill of maintaining good short-term performance.

Of the two emotions, fear is by far the stronger, as evidenced by the fact that stock prices fall faster than they go up. Afraid of losing money, people demonstrate a classic herd psychology upon hearing bad news, and often rush to sell a stock before the next investor. Many stocks drop 20 to 30 percent in price on a single day, even when the fresh information is less than striking. In the crash of 1987, the Dow Jones Index fell 23 percent in one day on no real news. Buying frenzies, in contrast, take place over longer stretches of time, such as weeks or months. Exceptions include the shares of takeover candidates and initial public offerings.

True takeover stocks are identified by a definitive offer from a respectable bidder. Because the offers typically involve a substantial price premium for control, investors rush in to acquire the takeover candidate’s shares at a price slightly below the offer. The size of the discount reflects uncertainties regarding the timing and ultimate completion of the bid, but a seasoned practitioner can make a reasoned decision. Occurring as frequently as real bids are rumored bids. Here, speculators acting on takeover rumors inflate a stock’s price in anticipation of a premium-priced control offer. Frequently, the rumors are from questionable sources, such as a promoter trying to sell his own position in the stock, so the price run-up is driven primarily by emotion, game theory, and momentum investing.

All of these factors play a role in the next hard-to-analyze business—the initial public offering (IPO). Many IPOs rise sharply in price during their first few days of trading, such as Chipotle Mexican Grill. It went public in January 2006 at $22 per share, and jumped 100 percent to $44 per share on the first day of trading. Within three months the stock was selling for $63. Unlike existing issues, an IPO has no trading history, so the underwriters setting the offering price make an educated guess on what its value is. At times this guess is conservative and the price rises accordingly. More frequently, the lead underwriters lowball the IPO price in order to ensure that the offering is fully sold, protecting themselves from their moral obligation to buy back shares from unsatisfied investors if the price were to fall steeply.

When underwriters get their publicity machines working and an IPO becomes hot, a herd psychology can infect investors, who then scramble over one another to buy in anticipation of a large price jump. At this point, a dedicated evaluation of the IPO has little merit. For a hot deal, many ...