![]()

1

Creating Rapid Widespread Engagement

Let’s cut to the chase. Without engagement, you won’t have buy-in. You are left with two alternatives: force and failure. There are occasions when force works. This book is not about failure.

Force works when it is okay if people don’t care. Or if they think you are wrong, giving bad, misguided, or rotten direction, and they’re willing to do what you say because it doesn’t affect them, is not detrimental in the long run, or the consequences of not doing what you say are more than they can bear.

In all of these situations, people will act on your ideas only so long as someone else keeps them in front of their nose. This is called the lighthouse effect. Wherever the change leader casts her attention, it is as if a light is projected, and the people inside that light spring into action, visibly demonstrating how they are enthusiastically carrying out their mandate. But just outside the light, activity quickly slips back into chaos.

This is typical of new ideas. It happens because their importance, significance, and value are not shared. Instead they are imposed. Shared value takes place when people get together to construct the meaning of a new idea or application. Imposed value happens when one person or one group sends an idea out—as if all that is required is that others understand their intentions.

This does not work for two reasons. First, people are overloaded with demands and barrages of information as well as multiple, conflicting mandates from above whose purpose they don’t understand. Second, even if you can get their attention (and you will with the techniques I show you), this way of communicating by commands and directives—“Let me tell you a better way,” “I have the answer; the information, knowledge, and research . . .” “I have been giving it good thought and consulted with the experts and we have figured it out”—is built on the wrong communication model.

I am going to show you a better one, one that works in the tumult of modern organizational life. This way of thinking about communication forms the core from which everything else in this book emanates.

In 1996 I was working on my first large-scale change initiative at the World Bank. I was part of the small team that won international recognition for the World Bank’s Knowledge Management (KM) effort. Working on this program was like driving on a racetrack that was changing its course while you steer: the course and the environment were always changing, but we made incredible progress.

In two years we went from an unfunded idea in a back room to $60 million in annual allocations, from no resources or incentives to every staff member receiving two weeks to dedicate to KM as well as having a component of their annual evaluation dedicated to it, from no recognition to international awards.

To make this happen we had to answer questions like these:

• How do you penetrate the conflicting demands and mental clutter that are part of everyday business life in the twenty-first century?

• How do you penetrate the assorted messages the media constantly bombard everyone with?

• After you have gotten through this confusion, how do you get people’s attention?

• Once you have their attention, what do you do with it to get people engaged, involved, and contributing?

• How do you coordinate this activity when you have no formal authority?

To answer these questions, let’s first look at the prevailing misunderstanding of how communication works, and then I will show you a much better way to think about it.

Most people intuitively use a communication model that originated in 1948 and was published by Shannon and Weaver in 1962.1 Although this model was great fuel for the information revolution, it is completely inadequate when it comes to person-to-person meaning making—which is what drives the rapid spread of new ideas.

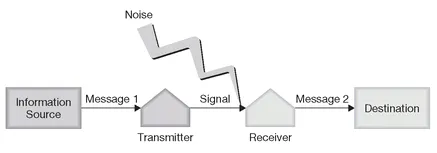

In its own domain, the Shannon-Weaver model is extraordinarily useful and can be credited with initiating much of modern information theory. It has been called by some the “mother of all models.”2 It states that you have an information source that develops a message that is sent using a transmitter. The signal travels and encounters noise on its way to a receiver where the subsequent message is delivered to a destination. (For a visual depiction, see Figure 1.1.)

The unquestioned assumptions that percolate in the minds of a typical communication team betray their use of this model. They go something like this:

We will talk to our president [Information Source] and craft a message that is easy for people to understand [Message 1]. We will place this message in various media including newsletters, posters, e-mails, Web sites, and town halls [Transmitters]. If we can get people to stop and read what we wrote, take the time to attend our events and listen to what we say, they will be exposed to our concepts and ideas [Signal]. Although they are uninformed, distracted and overloaded [Noise], they will hopefully read our writing when it appears in their inbox, come to our events, and listen to our presentations [Receivers]. They will then interpret what they have read and heard (Message 2) and understand what we are about. We will have reached them [Destination].

FIGURE 1.1 Shannon and Weaver’s Communication Model

Although the Shannon-Weaver model is great for sending digital signals, it is horrible for people trying to make sense of their world. We thinking humans are just not as simple as this model.

Making meaning is a much more complex task. For example, we don’t just decode information and understand it. If we did, you could pick up any book in a university library, read it cover to cover, and fully absorb what the author intends. But you cannot. You also need teachers and other students.

The reason we need teachers and other students is that we construct meaning socially, through interactions. We need the input of others to help us develop our ideas, place them in context, and make them relevant to our world, our experience. It is a collective project. This is called social construction.

We construct our understanding of the world through our relationships. As human beings we thrive on liaisons and partnerships. Social construction gets to the heart of how people make meaning together. It opens possibilities for reaching people who understand the world very differently, creating collaboration among diverse participants.

It is also a humane way of looking at communication, enabling compassion and kindness. Importantly it makes it possible to extend these qualities to technical and business-oriented interactions, bringing people together and generating esprit de corps even when people are from widely differing cultures. This is a critical milestone in communication.

Here is how social construction works. One person makes a statement of some kind, putting an idea out for the other to respond. Then there’s a reaction, an answer of some kind, which probably includes new information. For example, some part of the original idea makes sense and there’s an acknowledgment. Or some aspect appears wrong and there is a negative response or a correction. Or maybe it’s not clear yet, so there is a request for more information.

And so the participants go along together, making moves and countermoves, building a shared understanding or not being understood. Either way, an experience is generated that becomes a touch point for future interactions. And so together, back and forth, in messy iteration, understanding is fashioned.

Here’s an example:

Raj: Hi, Juanita, I have this new direction from our boss, Sylvan. He says I have to ask everyone for input before we plan our next conference. He isn’t sure we did such a good job last year of checking with everyone to see if their needs were being met as far as the agenda goes. He wants to me to ask you what you thought of last year’s conference.

Juanita: Last year’s conference was a disaster. But it wasn’t because Sylvan didn’t ask for input. As I remember, we had a lot of input. It was because he took us to the beach in the monsoon season. Nobody wants to go to the beach then! He should have taken us to an indoor resort that time of year or scheduled a time when the beach would be fun.

Raj: Okay, so you had the chance to contribute to the agenda, and the content wasn’t a problem; it was the location and time of year. Is that right?

Juanita: Yes, that’s right. But now that I am thinking about it, what is the process for putting together our agenda? Are you just going to ask everyone and then put together a hodgepodge of whatever people tell you?

Raj: No, we’re going to meet with Sylvan and do our best to outline what we think we should cover. At the same time, I’m going to talk with everyone and ask them what I’m asking you. Then we’re going to compare what we hear with what we put together on our own. At the end, Sylvan will look at everything and make some decisions.

Juanita: So we’re just going to do what he wants to do regardless?

Raj: I hope we can influence him with the results of these conversations. I think he’s pretty open to what we have to say. I don’t think he’s a tyrant.

Juanita: If anyone can influence Sylvan, it’s you, Raj. He loves the way you think. But I’d be surprised if he doesn’t dictate the agenda in the long run.

And so the conversation goes, to and fro, each one putting forth a proposition or question and the other reacting, refining, then putting forth a view until the conversation comes to an end. It’s not that a consensus is reached, but that Raj and Juanita have both developed and refined their sense of what’s meaningful through the interaction.

How does this apply to communicating new ideas and getting widespread engagement? Becoming adept in this kind of back-and-forth construction is where the value is. It is not in the technical smarts or the ability to articulate your own position. Those certainly play important roles, and any good idea is doomed without them. But the real challenge is in high-quality interaction, because that is where people decide if your message is relevant or worth their time and attention, and subsequently develop their sense of how best to act on it.

Here’s the kicker: professional expertise abounds. Technical know-how is in great supply. This is referred to as hard skill. But engagement, participation, and the genuine desire to contribute rely on goodwill, a cooperative attitude, sincere interest, and a desire to be helpful. In most change programs, these are in short supply. This is the soft stuff. In today’s work world, the soft stuff is the hard stuff.

This book is about getting the soft stuff right. This is the people part of change. You know the systems will work, but the people may not. And people can corrupt a perfectly good system. With the wrong attitude, they can let obstacles go untended, ignore necessary protocols, and turn their gaze away from difficult challenges. But when they share feelings of pride, a common loyalty, and fellowship, they will create synergies, become inspired to address difficult challenges, and unite in their efforts. This is what makes change happen fast.

Social Construction in a Nutshell

Social construction is a way of looking at how people build a common understanding and negotiate their way into the future. Here are five core principles:

1. The ways we come to understand the world and ourselves are created in relationships. All of our understandings spring from our interactions with others. During our lives, we develop a history of relationships—a set of traditions that come from the groups we belong to (family, professionals, jobs, and others). From this springs the ways we think about our experience and the world, including what we believe to be real, fair, and good.

2. We do not all interpret the world in the same way. Two people who observe the same event may come to different conclusions. This is normal. What is obvious to one person is not necessarily obvious to another.

3. Our shared interpretations of the world survive only if they are useful to us as individuals. If you want me to change my behavior, get involved in your idea, and take on the challenges it presents, then show me what difference it makes in my world and why I should care. Make it easy for me to see why I would get involved. Make it clear exactly how I can take action. Show me a spreadsheet that has no impact in my day-to-day life or ask me to read a report that does not change what I know or do, and there will be no additional shared understanding as a result.

4. Our understandings influence the ways we behave and possibilities for our future. For example, if we belong to a group that regularly recounts ho...