![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Mystery of Phi (1.618) and phi (0.618)

WHY IS THE GOLDEN RATIO (1.61803 . . .) of such interest to traders? Known by various names since the ancient Egyptians and Pythagoreans 570-490 BC, the first definition1 comes from Euclid (325-265 BC); The Divine Proportion, or Divina Proportione, by Luca Pacioli (1445-1517) was the earliest known treatise devoted to the subject and was illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci, who coined the name section aurea or the “golden section.” By any of its historical names, it is of little interest to investors, but investors rarely face the day-to-day battlefield of rapid global market action. Traders on the frontlines, however, live and die on their ability to measure risk and control their capital drawdown. To enter the tough markets of today requires the foresight to call what price a market will move toward. Of equal importance is our need to know where a market should not be trading so we can execute a timely exit plan.

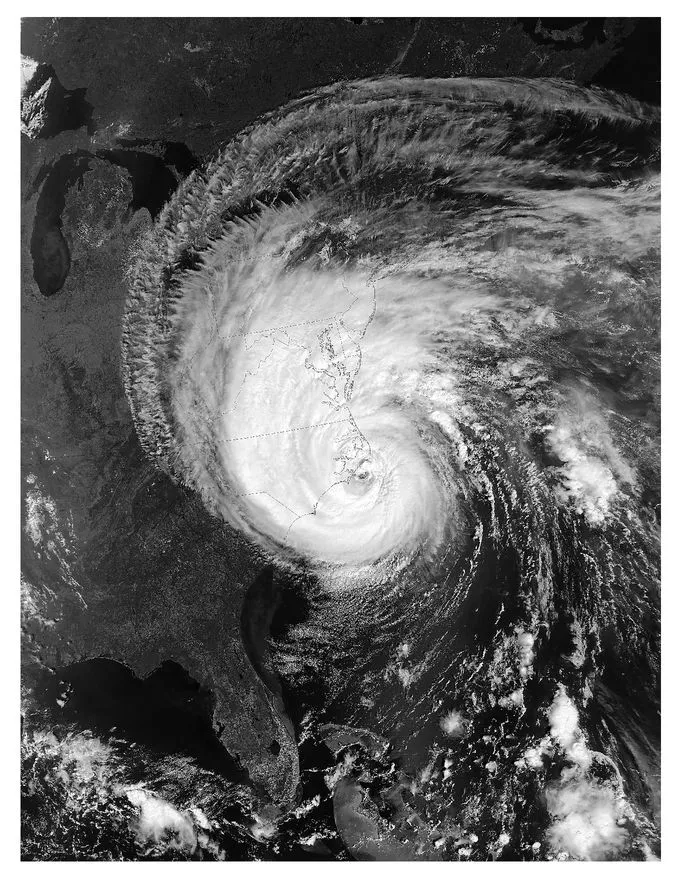

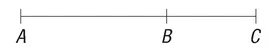

So how does an eloquent ratio that has captured people’s interest from the time of antiquity help and influence the decisions a trader must face today? The Golden Ratio (Figure 1.2) is a universal law that explains how everything with a growth and decay cycle evolves. Be it the spiral of the solar system, the spiral of a hurricane (Figure 1.1), the growth pattern of a nautilus seashell, or the spiral that forms at the start of life as a fern begins to unfurl from the ground on a spring day. Plato (circa 427-347 BC) in the Republic asks the reader to “take a line and divide it unevenly.” Under a Pythagorean oath of silence not to reveal the secrets of the mysteries, Plato posed questions in hopes of provoking an insightful response. So why does he use a line, rather than numbers? Why does he ask you to divide it unevenly?

FIGURE 1.1 Hurricane Isabel

Source: NASA

FIGURE 1.2 The Golden Ratio

To answer Plato and how this may connect to the needs of all traders today, we first must understand ratio and proportion. All living things from large to small, including markets, must abide by the same divine blueprint. As a result, the more traders understand how a ratio called Phi (1.618) influences our lives, the clearer we can look into the face of a grander plan and witness a force acting upon our markets that demands our respect, comprehension, and humility. As a trader’s knowledge deepens, he can see in advance a mathematical grid that determines future market movement. But few people truly understand the forces at play and never develop beyond the basic theory that is insufficient to adjust to the natural expansion and contraction cycles found within all markets in both price and time.

Ratio, Means, and Proportion

Ratio (logos) is the relation of one number to another, for instance 4 : 8, stated as “4 is to 8.” However, proportion (analogia) is a repeating ratio that typically involves four terms, 4: 8 :: 5: 10, stated as “4 is to 8 is as 5 is to 10.” The Pythagoreans called this a four-termed discontinuous proportion. The invariant ratio here is 1 : 2, repeated in both 4 : 8 and 5 : 10. An inverted ratio will reverse the terms, so it can be said, 8 : 4 is the inverse of 4 : 8, and the invariant ratio now is 2 : 1.

Few traders truly grasp the concepts of ratios and become bound by this limitation from doing more advanced work. As example, standing between the two-termed ratio and the four-termed proportion is the three-termed mean, in which the middle term is in the same ratio to the first as the last is to it. The geometric mean between two numbers is equal to the square root of their product. Therefore, it can be said, the geometric mean of 1 and 9 is √(1 × 9), which equals 3. This geometric mean relationship is written as 1 : 3 : 9 or inverted, 9 : 3 : 1. It can also be written more fully as a continuous geometric proportion where these two ratios repeat the same invariant ratio of 1 : 3. Thus, 1 : 3 :: 3 : 9. The 3 is the geometric mean held in common by both ratios. This is the interlacing mathematical glue that binds them together.

The Pythagoreans called this a three-termed continuous geometric proportion. The Golden Ratio has a three-termed continuous geometric proportion. As viewed in Figure 1.2, the Golden Ratio is the ratio that results between two numbers A and C when a line is divided, so that the whole line, AC, has the same ratio to the larger segment, AB, as the larger segment, AB, has to the smaller segment, BC. AC : AB :: AB : BC. The geometric mean held in common by both ratios is B or 0.618. As B is the geometric mean of A and C, it can be written as A : B : C. We traders will use this ratio to define the mathematical grid a market is forming to build future price swings and pivots.

Pythagoras

Pythagoras (570-490 BC) was born in Ionia on the island of Samos in Greece. He eventually settled in Crotone, a Dorian Greek colony in southern Italy in 529 BC. Pythagoras’s thought was dominated by mathematics, and the Pythagorean philosophy can be summarized as: Only through mathematics can anything be proven, and by mathematical limit the unlimited can take form. The thinking of the Pythagoreans was exceedingly advanced for their time in many ways. As a simple example, they knew there must be a substance in the air to allow sound to travel from one person’s mouth to another’s ears. They knew nothing about atoms or kinetic energy, but already had the conceptual idea. Pythagoras’s school gradually formed into a society or brotherhood called the Order of the Pythagoreans. Growing in wealth and power, Pythagoras2 was murdered when their meetinghouse was torched. The remaining Pythagoreans were scattered across the Mediterranean. Pythagoras wrote nothing down and none of his followers’ original papers on mathematics survived. However, after the attacks on the Pythagoreans at Crotone, they regrouped in Tarentum in southern Italy. Collections of Pythagorean writings on ethics3 show a creative response to their troubles.

In a biography of Pythagoras written seven centuries after Pythagoras’s time, Porphyry (AD 233-309) stated the Pythagoreans were divided into an inner circle called the mathematikoi (“mathematicians who study all”) and an outer circle called the akousmatikoi (“listeners”). Pythagoras’s wife Theano and their two daughters led the mathematikoi after Pythagoras’s death.4 The early work of the Pythagoreans on the Golden Ratio might have been lost if it had not been for a woman: Theano, who was a mathematician in her own right. She is credited with having written treatises on mathematics, physics, medicine, and child psychology, although nothing of her writing survives. Her most important work is said to have been a treatise on the principle of the golden mean. In a time when women were usually considered property and relegated to the role of housekeeper or spouse, her work was in keeping with Pythagoras’s views that allowed women to function on equal intellectual terms in his society.

FIGURE 1.3 Woman Teaching Geometry 1309. It is rare to find a woman teaching Geometry, one of the sacred sciences, as depicted in this painting from 1309. It shows her teaching a group of young monks.

Most of the concepts developed by the Pythagoreans gave credit to Pythagoras himself. So it is hard to unravel his specific accomplishments from his followers. But Aristotle, in his

Metaphysica, sums up the Pythagorean’s attitude toward numbers:

The so-called Pythagoreans, who were the first to take up mathematics, not only advanced this subject, but saturated with it, they fancied that the principles of mathematics were the principles of all things.5

The Pythagoreans knew just the positive whole numbers, zero, and negative numbers, and the irrational numbers didn’t exist in their system. Despite this limitation about irrational numbers, Pythagoras6 is believed to have discovered the Golden Ratio through sound—the sound of two hammers of different weights hit an anvil producing a harmonic pitch of divine perfection. This fact, that the origin of the Golden Ratio was discovered through a harmonic ratio, will have implications in the final chapters of this book. It will change how traders should think and apply the Golden Ratio to analyze the markets.

While accounts of Pythagoras’s travels differ, historians agree he traveled to many countries to study with the masters of his time. Many historians believed he was an initiate of the ancient Egyptian priests, as was Plato and Euclid. But why is this of interest in the business of trading today’s markets? The ancient priests of Egypt believed that only a student well versed in the ancient quadrivium—the study of seven disciplines that included arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy—would be able to solve the problems they faced in their life. This philosophy for attaining wisdom is no different than what is needed to understand the full potential of the Golden Ratio applied to our global market puzzles today. It is only through a study of ratios can one understand the concepts of proportion, symmetry, harmonics, and rhythm. Many traders erroneously assume that markets move in fixed intervals within linear dimensions. Markets do not move in such a manner. Future market price swings will expand or contract in measurable ratios derived from multiple prior price swings. Markets are living breathing entities, and the industry is stuck with outdated assumptions and applications that we must reevaluate. In order to move forward beyond the elementary, we must revisit the teachings of the past so we can reprogram our thinking.

It is generally accepted that Plato offers the world the earliest written documentation of the Pythagoreans.7 In 387 BC, Plato founded an academy in Athens, often described as the first university. Plato loved geometry also. His school included a comprehensive curriculum of biology, political science, philosophy, mathematics, and astronomy. Over the doors to his academy were the words αγεωµερητoς µηδεıςεıσıτω, meaning “Let no one destitute of geometry enter my doors.”

It was long thought both Pythagoras and Plato were by-products of Egyptian schooling. No proof to this regard was available until recently. The highly respected Egyptian Egyptologist Dr. Okasha El-Daly has released in his book, Egyptology: The Missing Millennium,8 proof that the Greek philosopher Pythagoras had been a student of the carefully guarded wisdom of the ancient Egyptian high priests. Until now, this was only suspected to be true. During a dinner in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, with Dr. El-Daly, he commented to me that the ancient Egyptians had such high regard for Pythagoras that El-Daly found Egyptian papyrus in the British Museum vaults documenting the cons...