![]()

PART I

How Our Attitudes Underpin Our EI

![]()

1

Why EI now?

The ever-increasing pace of change

We live in a world where change has to be taken for granted, and where the rate of change appears to be increasing steadily (though probably the rate at which it is increasing is itself increasing). This is due to the effects of a combination of factors:

• advances in technology, particularly information and communication technology;

• globalisation;

• the Internet;

• breakdown of cultural and, since the end of the cold war, political barriers, leading to more rapid exchange of ideas;

• the spread of literacy and higher education;

• greater openness to the contribution of different cultures;

• the decline of conservative institutions, such as the extended family, and authoritarian regimes.

Learning to live with change, to embrace it and not to be frightened by it is a task for us all, and involves not so much cognitive abilities as appropriate feelings and attitudes.

Leadership, too, requires a new approach. As business strategists such as Dr Lynda Gratton of the London Business School and Professor Richard Scase of the University of Kent are predicting, tomorrow’s leaders will need to cope with more demanding customers and a more discerning employee base. The leaders of the future will need to be facilitators - leaders who enable others to develop their own leadership and potential. They will also be collaborative leaders, highly skilled in developing and sustaining mutually beneficial partnerships and able to influence and lead non-employees and stakeholders. These both require a new set of skills and attitudes for leadership - emotionally intelligent skills and attitudes.

A crisis of meaning

For most of the history of mankind people have been overwhelmingly preoccupied with what Maslow would call safety and survival needs: warding off physical threats, getting enough to eat and drink and bringing up the next generation. With the coming of the Industrial Revolution, people went to work to get money to house and feed themselves. It is just over 100 years since Thorstein Veblen published his book on The Theory of the Leisure Class, and in developed countries the majority of the population is now relatively leisured - or could be if they chose to be. Many people are no longer prepared to exchange hours of boring drudgery and partial loss of liberty for cash.

For many years this exchange has been fostered by the triumph of Western materialism: people wanted more and more, often for purposes of conspicuous consumption, and for that they needed more and more money. Increasing material wealth has not brought in its train increasing happiness: having too little money may make you anxious and unhappy, but above a basic minimum having more will not make you happier. The triumph of materialism in the West to date has, therefore, been an empty triumph, and, coinciding as it has with a decline in adherence to revealed religion, has led to a psychological revolution: the evolution of humanism.

Humanism posits the human being, with his/her needs and aspirations, as the central value of our society and as the solution to the crisis of meaning which has assailed Western culture ever since the abandonment of the selfish materialism of the “me” generation at the end of the twentieth century. Nowadays, many people seek to spend their lives not just earning money for themselves at whatever personal cost, but working in accordance with their values, which include the promotion of a society in which human rights are completely realized: the right to health, education, freedom, spirituality, search for the meaning of life and an existence with dignity. As well as seeking work which accords with their values, educated employees in particular - those belonging to what economists and sociologists would traditionally have called the white-collar and managerial class - seek work that fosters their self development, that allows them to grow towards what they could possibly be. In Maslow’s terms, they seek opportunities for self actualisation at work. We take a look in Chapter 5 at how we can create more meaning in our working lives through developing our emotional intelligence.

The arrival of EI

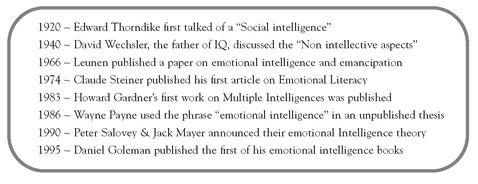

The history of emotional intelligence is most easily set out in tabular form:

Table 1.1 The history of Emotional Intelligence.

And here we are, some ten years on from Daniel Goleman’s acclaimed book, and emotional intelligence hasn’t gone away. In fact there are more and more books, articles and references being made about EI now than there ever have been - this book included!

So why has it stood the test of time? Briefly because of the connection between levels of emotional intelligence and levels of performance, particularly in senior jobs: anyone interested in performance improvement (and who isn’t?) needs to be interested in emotional intelligence. (We address the connection between EI and performance more specifically on page 22.)

Furthermore, EI hasn’t just passively “stood the test of time” in the sense of proving not to be a short-lived flash in the pan; as the years pass it is coming to be seen as more and more important.

This is, in summary, because the changes in society and work organisation which have taken place over recent years, and which are continuing, mean that there are new requirements of today’s and tomorrow’s organisation leaders and members, and they all demand emotional intelligence.

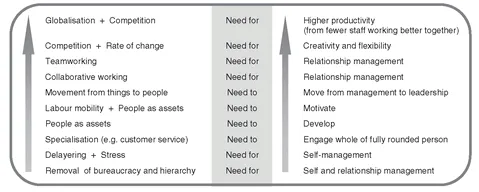

Figure 1.1 sets out the societal changes and the new organisational requirements to which they are giving rise.

Figure 1.1 Societal changes and the associated new organisational requirements.

None of these new or enhanced requirements is technical; they all involve aspects of emotional intelligence.

Why is EI the answer?

Our answers to this question lie in this book, but here is an overview.

Traditionally, people were employed largely for their muscle power - to do physical things. Increasingly during the second half of the last century they were employed for their brain power - to do mental things. But the new requirements of organisations and their leaders listed above, which translate into new requirements of their employees by the leaders of organisations in the 21st Century, require that people bring their whole selves to work rather than just their muscles and/or their brains. Similarly, employees want the fulfilment of involving and developing their whole selves, rather than just their muscles and/or their brains, at work.

Our sense of ourselves is largely tied up with our feelings, and this development entails the recognition of organisation members as being feeling beings as well as thinking beings. Similarly, our values are related to our feelings and attitudes, not just our thoughts and ideas. Again, employees who are value-driven need to be recognised as being feeling beings as well as thinking beings. Since emotional intelligence is about integrating feeling and thinking, it is clear that developing EI in organisations, in teams, in managers and in employees is the appropriate response to these developments.

From management’s point of view, the above changes have led to a significantly increased need in themselves and their employees for effective self management and relationship management, which, as we shall see later, are two key EI processes; for creativity and flexibility, both aspects of EI, and consequently to the need to consider staff as fully rounded human beings, to develop them, to motivate them and to lead them rather than just manage them, all part of the emotionally intelligent approach to organisation management.

To boil it all down to one statement: emotional intelligence is highly correlated with performance, and since we are all in the business of performance improvement, we all need to focus on emotional intelligence.

Reference

Veblen, T. (1994) The Theory of the Leisure Class, Dover Publications. First published in 1899.

![]()

2

IQ and EI

A word about the term EQ. In the early days of the study, and the promotion, of emotional intelligence, this label was adopted by those who wished to persuade what they thought would be a sceptical, and largely male, audience of the “hard” and respectable nature of the concept. By creating an acronym of Emotional Quotient they created a term that enabled EI, or as they labelled it EQ, to be put in the same frame as cognitive intelligence, or IQ.

EI testers then set about creating questionnaires to help you ascertain your EQ score, by which you could measure “how emotionally intelligent you are compared with other people”, just as your IQ score measures how cognitively intelligent you are compared with other people.

But the creation of a single score of EQ involved suggesting that our emotional intelligence can be reduced down to just one thing, by which we can then be compared with other people. Which is not the case: our EI is made up of a multitude of components, each of which we can have to varying degrees and each one of which represents a different aspect of the way we handle or use feelings. To reduce this down to one score, a single number, misses the point and only serves to give us yet another measure by which we can judge ourselves or others.

In this book which outlines the model of emotional intelligence adopted by the Centre for Applied Emotional Intelligence (CAEI), we demonstrate how meaningless it is to attempt to represent our emotional intelligence with a single score.

The two sides of emotional intelligence

To begin with, we can divide the supposedly unitary concept of emotional intelligence into two: the intrapersonal and the interpersonal, as shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Managing our relationships with ourselves and others.

The arrows in this model represent causation. The chief causal connections are downwards: we can only manage ourselves effectively to the extent that we are self aware, and we can only manage our relations with others effectively to the extent that we are aware of them and their feelings. The bottom horizontal arrow is fairly obvious: I can only manage my relationship with you effectively to the extent that I can manage myself. If every time you say something that irritates me I lose my temper and bop you on the nose, then it is unlikely that we will have a good relationship. The top horizontal arrow is perhaps a little more esoteric. It refers to the fact that we use our body as a source of information, non-cognitive information, about other people (“hunches”, “gut feelings”, “instinctive reactions”, “intuition”), and to the extent that we are unaware of what our body is telling us we will also be unaware of the other. (The exceptions appear to be sociopaths and conmen: highly aware of others but not in touch with themselves.)

The three-layered cake

In order to understand how to measure emotional intelligence properly, we need first to understand what is being measured.

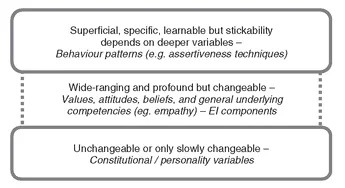

Figure 2.2 The three-layered cake.

Imagine we are like a three-layered cake - a Victoria Sandwich - with a layer of sponge on the top and on the bottom and a juicy, fruity layer in between (Figure 2.2)! The top layer represents the overt part of us: what we do. This is relatively easily changed: we can go on a training course and be taught new patterns of behaviour - such as being more assertive, for example. However, whether these newly learned behaviours are retained and integrated into our repertoire of behaviour, whether they “stick”, depends on the impact of deeper variables underneath. In our example of assertiveness, if we don’t believe we are as important as other people are, then it will be difficult consistently to stick up for our rights, even if we have learned how to do so.

In the bottom layer of the c...