- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tropical Conservation Biology

About this book

This introductory textbook examines diminishing terrestrial and aquatic habitats in the tropics, covering a broad range of topics including the fate of the coral reefs; the impact of agriculture, urbanization, and logging on habitat depletion; and the effects of fire on plants and animal survival.

- Includes case studies and interviews with prominent conservation scientists to help situate key concepts in a real world context

- Covers a broad range of topics including: the fate of the coral reefs; the impact of agriculture, urbanization, and logging on habitat depletion; and the effects of fire on plants and animal survival

- Highlights conservation successes in the region, and emphasizes the need to integrate social issues, such as human hunger, into a tangible conservation plan

- Documents the current state of the field as it looks for ways to predict future outcomes and lessen human impact

"Sodhi et al. have done a masterful job of compiling a great deal of literature from around the tropical realm, and they have laid out the book in a fruitful and straightforward manner…I plan to use it as a reference and as supplemental reading for several courses and I would encourage others to do the same." Ecology, 90(4), 2009, pp. 1144–1145

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tropical Conservation Biology by Navjot S. Sodhi,Barry W. Brook,Corey J. A. Bradshaw in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Diminishing Habitats in Regions of High Biodiversity

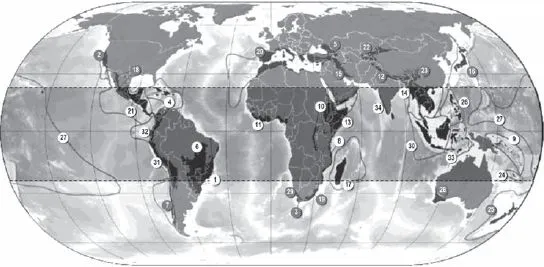

In this chapter, we review the loss of native habitats across the tropics: the region that lies between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, i.e. 23.5° north and south of the equator (Figure 1.1). The word ‘tropics’ is derived from the Greek word tropos meaning ‘turn’. The average annual temperature of the tropics is higher and the seasonal change in temperature is less pronounced than in other parts of the world because the tropical zone receives the rays of the sun more directly than areas at higher latitudes. The seasons in the tropics are marked not by large temperature fluctuations, but by the combination of winds taking water from the oceans and creating seasonal rains, called monsoons, over the eastern coasts. Several different climatic types can be distinguished within the tropical belt. Distance from the ocean, prevailing wind conditions and elevation are all contributing elements. Tropical highland climates, which have some characteristics of temperate climates, also occur where high mountain ranges are located. The tropics are the world’s largest reservoirs of humid forests (Amazon, Congo Basin and New Guinea); the immense vegetative growth of these lush ‘rain forests’ is attributable to the monsoon rains. Owing to decreasing rainfall towards the northern and southern limits of the tropics, climatic conditions favour low-latitude savanna, steppe and desert biomes. High temperatures and abundant rainfall make rubber (Hevea brasiliensis), tea (Camellia sp.), coffee (Coffea robusta and C. arabica), cocoa (Theobroma cacao), spices, bananas (Musa spp.), pineapples (Ananas sp.), oils and timber the leading agricultural exports of tropical countries.

Ironically, the tropical region where two-thirds of the world’s biodiversity is found is also the backdrop of massive contemporary loss of native habitats, mimicking the historical land conversion witnessed over the past few centuries in Europe and the temperate regions of North America and Australia. As a result of this mega-rich biodiversity and unprecedented loss of habitats, the tropical region has obviously attracted a high level of interest from conservationists. We first present an overview of habitat loss, namely in rain forests, mangroves and tropical savannas and limestone karsts, and then follow with a report on the known and postulated drivers of native habitat loss in the tropics. Finally, we identify the areas in immediate need of conservation action by discussing the concept of biodiversity hotspots.

Figure 1.1 A map of the world showing the tropics and the distribution of ‘biodiversity hotspots’ outside (grey circles) and within (white circles) the tropics (shaded region): 1, Atlantic forest; 2, California floristic province; 3, Cape Floristic region; 4, Caribbean islands; 5, Caucasus; 6, Cerrado; 7, Chilean winter rainfall – Valdivian forests; 8, coastal forests of eastern Africa; 9, East Melanesian islands; 10, eastern Afromontane; 11, Guinean forests of west Africa; 12, Himalaya; 13, Horn of Africa; 14, Indo-Burma; 15, Irano-Anatolian; 16, Japan; 17, Madagascar and Indian Ocean islands; 18, Madrean pine–oak woodlands; 19, Maputaland–Pondoland–Albany; 20, Mediterranean basin; 21, Mesoamerica; 22, mountains of Central Asia; 23, mountains of southwest China; 24, New Caledonia; 25, New Zealand; 26, Philippines; 27, Polynesia–Micronesia; 28, southwest Australia; 29, Succulent Karoo; 30, Sundaland; 31, tropical Andes; 32, Tumbes–Chocó-Magdalena; 33, Wallacea; 34, western Ghats and Sri Lanka. (After conservation.org. Copyright, Conservation International.)

1.1 Loss of native habitats

If human impact on the natural environment continues unabated at its present rate or increases in severity, then by the turn of the century the resulting changes in land use will have exerted a profound and irreversible effect on tropical biodiversity (Sala et al. 2000). Habitat loss will probably have far greater effects on terrestrial ecosystems in the tropics than other drivers such as climate change, elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) levels and invasive species (Sala et al. 2000). However, among these factors there are likely to be large and complex interactions that exacerbate the foreseen problems. Rain forest loss, degradation and fragmentation are the most widely publicized examples of habitat loss in the tropics; indeed, human activities, such as logging, are degrading and destroying tropical rain forests at a rate that has no historical precedence (Jang et al. 1996; Whitmore 1997; W.F. Laurance 1999). Given that the vast majority of the earth’s terrestrial biodiversity is harboured in these threatened and little-studied biomes (E.O. Wilson 1988; Myers et al. 2000; Sodhi and Liow 2000), they are critical for conservation.

1.1.1 Rain forest depletion

Tropical forests cover 7% of the earth’s land surface, yet they support over 50% of described species, plus a large number of undescribed taxa (W.F. Laurance 1999; Dirzo and Raven 2003). They are also critical for global carbon and energy cycles [Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) 2002]; therefore, tropical forests are not only crucial for biodiversity conservation, they also play pivotal roles in moderating global climate change. Despite this importance, more than 40% of original tropical forests have been cleared in Asia alone (Wright 2005).

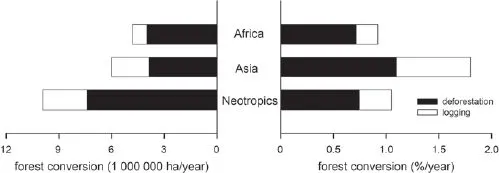

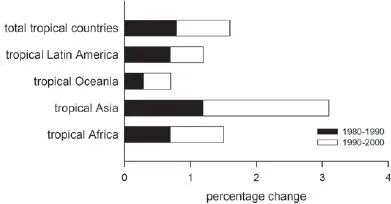

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has reported that countries with the largest annual net forest losses between 2000 and 2005 are all situated in the tropics (FAO 2005). These countries include Brazil, Indonesia, Sudan and Myanmar, and they collectively lost 8.2 million hectares (ha) of forest every year between 2000 and 2005 (FAO 2005). W.F. Laurance (1999) used data provided by the FAO (1993) on forest cover change from 1980 to 1990 and estimated that 15.4 million ha of tropical forest is destroyed every year, with an additional 5.6 million ha being degraded through activities such as selective logging. Overall, an average of 1.2% of existing tropical forests is degraded or destroyed every year (Whitmore 1997; W.F. Laurance 1999). In terms of absolute loss of area, forest conversion is the highest in the neotropics (South and Central America: 10 million ha/year), followed by Asia (6 million ha/ year) and Africa (5 million ha/year). However, if we consider forest conversion relative to the existing forest cover in the region, Asia clearly tops the list (W.F. Laurance 1999) (Figure 1.2), with 1.5 million ha of forest removed each year from the four main Indonesian islands of Sumatra, Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo), Sulawesi and West Papua (Indonesian New Guinea) alone (DeFries et al. 2002). Even the so-called ‘protected forests’ in the tropics are not safe from plunder – of 198 protected areas surveyed, 25% have been losing forests within their administrative boundaries since the 1980s (DeFries et al. 2005).

Figure 1.2 Relative and absolute rates of forest conversion in the major tropical regions throughout the decade of the 1980s. (After W.F. Laurance 1999. Copyright, Elsevier.)

Worryingly high as they are, whether the FAO values are accurate is controversial because they may fail to include catastrophic events (such as the vast 1997–98 forest fires that occurred in Indonesia) and may erroneously include forestry plantations as native forest cover (Matthews 2001; Achard et al. 2002). Deploying remotely sensed satellite imagery, Achard et al. (2002) reported that tropical forest loss may be much lower (5.8 million ha/year) than FAO estimates. Yet even Achard et al.’s estimates have being questioned. It has been argued that their lower estimates of forest loss may be unrepresentative, owing to the fact that they sampled only 6.5% of the humid tropics (Fearnside and Laurance 2003). Nevertheless, despite the different methods used, Achard et al. (2002) also found, as reported earlier by W.F. Laurance (1999), that rates of deforestation and forest degradation are highest in Asia (Figure 1.3).

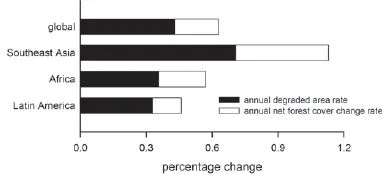

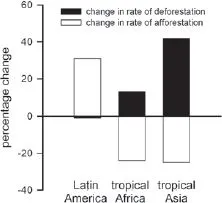

The expansion of agriculture in the humid tropics is the main culprit in this devastating forest loss, with more than 3 million ha of forest converted annually by this activity (Achard et al. 2002). Although native forest loss in tropical Latin America seems to be decelerating, in a particularly disconcerting trend it continues to accelerate in tropical Asia (Matthews 2001) (Figure 1.4). This trend is further corroborated by a satellite imagery study of Latin America, tropical Africa and Asia by M.C. Hansen and DeFries (2004), who reported that deforestation appears to be accelerating in the last two regions (Figure 1.5). Depending on factors such as soil fertility and proximity to remnant forests (i.e. seed source), forest regeneration can proceed in abandoned areas following disturbance (Chazdon 2003). These secondary forests could be crucial for global carbon cycles and conservation of some forest biota (Wright 2005). However, about a quarter of regenerating forests are also being lost in tropical Asia and Africa (M.C. Hansen and DeFries 2005), with an increase of this forest type found only in Latin America (Figure 1.5).

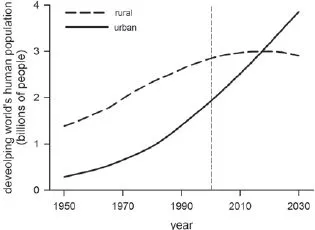

There has also been controversy as to whether the global deforestation rate is subsiding over time. FAO data show that globally there has been a 31% decrease in the deforestation rate over the past two decades. But a study by M.C. Hansen and DeFries (2004) showed that deforestation has, in reality, accelerated by the same amount during the same period. Wright and Muller-Landau (2006) argue that the deforestation rate will slow down in the future due to a decrease in human population growth and increasing migration to urban centres. They argue that such changes in human demographics will be conducive to forest regeneration. However, Brook et al. (2006a) dispute this scenario because of decoupling between rural and urban human populations (Figure 1.6); even if deceleration does occur, it may be a little too late to stop the mass extinction of biodiversity in the tropics caused by the momentum of past habitat loss (see Chapter 9).

Figure 1.3 Mean annual estimates of deforestation in the humid tropics from 1990 to 1997. (Data derived from Achard et al. 2002.)

Figure 1.4 Worsening deforestation rates in all tropical regions except Latin America. (Data derived from Matthews 2001.)

Figure 1.5 Positive increase in rate of deforestation (filled bars) and decrease in rate of afforestation (blank bars) in tropical Africa and Asia, with only Latin America showing opposite trends. (Data derived from M.C. Hansen and DeFries 2004.)

Globally, 0.8% of native tropical forests (primary and secondary forests, excluding plantations) are likely to be lost each year (Matthews 2001), and in countries plagued by civil war, such as Burundi and Rwanda, the rates of loss can be much higher (Table 1.1). Perhaps most dramatically, it has been estimated that, by 2010, human actions will have caused almost complete destruction of native lowland (< 1000 m elevation) forests from the hyper-biodiverse regions of Sumatra and Kalimantan (Jepson et al. 2001). Such a massive loss of habitat will almost certainly have profound incidental effects on the region’s spectacular megafauna, such as the Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) and Asian elephant (Elephas maximus). Tropical countries with the highest deforestation rates (> 0.4% deforestation annually) usually have a large percentage of the remaining dense forests (> 80% canopy cover) near deforestation activities, thus indicating that these areas also remain highly vulnerable to deforestation (M.C. Hansen and DeFries 2004) (Figure 1.7).

Figure 1.6 Trends in rural and urban human population growth in the world’s developing countries. Vertical dashed line separates past and projected figures. (After Brook et al. 2006a. Copyright, Blackwell Publishing Limited.)

The lowland tropical rain forests are particularly imperilled owing to their ready accessibility to an expanding human population and their increasing conversion to logging concessions, agricultural land and urban areas (Kummer and Turner 1994). In addition to this widespread forest type, other forest types also existing in the tropics are being destroyed (Whitmore 1997; Figure 1.8). For example, montane/submontane (usually > 1000 m elevation) rain (cloud) forests provide timber, fuel wood, soil and catchment protection. This forest type makes up 12% of the existing tropical forests worldwide, and it is currently being cleared at a rate twice that of the global average [Long 1994; Whitmore 1997; IUCN (The World Conservation Union) 2000]. In fact, montane forests are lost at a relatively higher annual rate than lowland tropical forests (Figure 1.9; Whitmore 1997). Montane forests, because of their unique environmental conditions (e.g. cooler temperatures), support a high degree of endemism. For example, the proportion of endemic moths is at least twice as high in montane forests than in their lowland counterparts in Malaysian Borneo (Chey 2000). Montane forests have a low recovery potential following disturbance (Ohsawa 1995; Soh et al. 2006). However, despite their fragility and high endemism, human activities continue to threaten these vulnerable forests (Ohsawa 1995; IUCN 2000).

Eighty-five per cent of global forest loss occurs in tropical rain forests (Whitmore 1997). However, the tropics also contain seasonal, dry or monsoonal deciduous forests. These generally lie below 1000 m elevation in regions such as Central America, Madagascar and Asia (Thailand) (Ruangpanit 1995; W.F. Laurance 1999), and constitute 33% of the existing tropical forests in the world (Whitmore 1997). Owing to their proximity to human habitation, seasonal forests also suffer a similar fate as lowland rain forests. In fact, seasonal forests are often grouped, for convenience, with rain forests, and are thus included in some of the regional deforestation calculations (e.g. Achard et al. 2002). Indeed, it is estimated that seasonal forests are being lost at the highest rate of any forest type (Figure 1.9) (Whitmore 1997). In some regions, such as Central America and Madagascar, more than 96% of these forests have already been destroyed (K...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Diminishing Habitats in Regions of High Biodiversity

- 2 Invaluable Losses

- 3 Broken Homes: Tropical Biotas in Fragmented Landscapes

- 4 Burning Down the House

- 5 Alien Invaders

- 6 Human Uses and Abuses of Tropical Biodiversity

- 7 Threats in Three Dimensions: Tropical Aquatic Conservation

- 8 Climate Change: Feeling the Tropical Heat

- 9 Lost Without a Trace: the Tropical Extinction Crisis

- 10 Lights at the End of the Tunnel: Conservation Options and Challenges

- References

- Index