![]()

PART I

GONE FISHING

![]()

CHAPTER 1

HOW DO I START MAKING MONEY?

There are over 1,500 stocks listed on the Australian Stock Exchange, and with diligent research, you might get to really know perhaps 10 of them, or even 30. This ignores the other 1,470 stocks, many of which offer excellent trading opportunities. You need a short-cut that allows you to use your knowledge, and the actions of others, to guide you to better opportunities. We put together several short-cuts and a combination of solutions in this book.

Many people use trading as a part-time occupation to deliver a full-time income and this is a useful approach. The shift from earning money to making money earn money for you is important. Unless you accept that the objective is to make your money work for you, your approach to the market is most likely to be a gambler’s approach, looking for quick money. A successful trader develops a different view of the world of money, and the relationship between capital and income.

A typical example of these different views is between those who want to immediately develop a replacement income for their wages, and those who want to use trading to supplement their income. The latter group focus on the most effective use of capital. They are not after a big hit — the gambler’s approach. They look for the best return on their capital rather than focus on the size of the dollar return.

Protecting your capital, growing your capital and finding the best return are the core tasks for the trader and investor. Where and how to start are common questions. Some people examine their current job with its heavy time demands and decide the life of a share trader sounds easy in comparison. The common questions about becoming a full-time share trader include:

1 Do I need to become a full-time share trader to benefit from the market?

2 What is the difference between traders and investors?

3 How should I prioritise my learning curve?

4 What seminars, books and resources should I invest in?

5 Where do I get independent analysis?

6 What should I read?

7 Do I need exclusive, and often expensive, information?

8 Where do I start?

In this chapter we examine the first six questions. The last two questions call for dedicated chapters. This is our starting point for the market. Unless we believe it is possible to learn how to succeed in the market we cannot take the first step. Look ahead for a moment. After we embark on this journey we soon face a daunting obstacle — how to find suitable trading or investment opportunities. This is easier than it first appears. The more difficult task is reducing this list from 10 or 15 to just a single stock. Finding the best candidates means we subject each stock to a further six tests. Each part in this book is built around one of these tests, except the detour in Part VII, in which we look at Darvas-style trading. They are combined in the final performance test. The tests are:

- A selection test — covered in this part.

- A visual test.

- A trend line test.

- A character test using a Guppy Multiple Moving Average.

- An entry test using a count back line.

- A position size test.

- A performance test.

Full-Time or Part-Time?

Do I need to become a full-time share trader to benefit from the market? The short answer is ‘No’. Full-time share traders are relatively rare and they tend to work for institutions. Full-time private traders are rarer. It is a skilled profession but unlike many professions, it also offers a part-time component. Trading skills are applied to a single trade, or to multiple trades.

When I first started, trading provided a very useful supplement to my wages income. Bank interest on my meagre savings was very high and delivered an extra $1,000 a year. Active management of market investments delivered $10,000 or more a year. Trading was clearly the best use I could make of my savings capital.

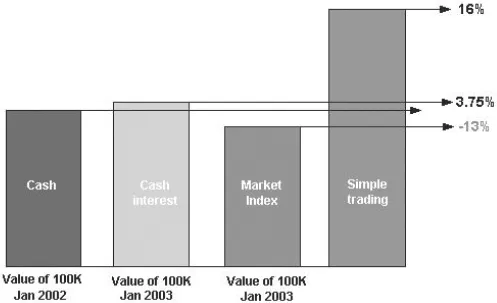

The chart in Figure 1.1 shows some sample returns made from part-time trading achieved by a group of my students in Darwin who attended an eight-week course. They made their selections in lesson 1 at a time when they knew little about trading the financial markets. We applied a simple trend trading strategy discussed in the next chapter. Their weekly management of the trades delivered a 16% return on capital over eight weeks.

Trader or Investor?

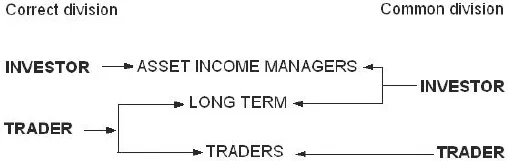

What is the difference between traders and investors? This is a popular question that is often answered incorrectly. The correct division is shown on the left in Figure 1.2.

The investor is an asset income manager. He buys an asset such as a house, a government or corporate bond or a share because the asset delivers an income stream. He is particularly concerned about his return on capital as defined by the interest paid, the coupon rate or the dividend rate. When he makes these calculations he starts from the price he paid for the asset and looks at the income generated based on the original price.

If the current price of the asset falls, but the income generated remains much the same, he sees no cause to sell. If the price of the asset rises dramatically he may be tempted to sell to collect a capital gain. This extra capital is then employed to buy another asset such as a rental property, more bonds or other dividend-paying shares available for a low cost.

When the investor makes a decision about how well, or poorly, his asset is performing he measures the rate of income against his original cost — not the current market price of the asset.

The trader has a different objective. He wants to buy a product from a supplier at one price and sell the product to the consumer at another price. His income comes from the difference between the two prices — the price he paid, and the price he receives. Trading is the activity which drives business. It does not matter if you are selling tinned food, televisions, computers, office furniture or shares. The underlying principle is unchanged. We buy an item for one price and intend to sell it to a customer at a higher price.

The successful businessman trader buys items he knows other people want. He buys items in demand because he can resell those items at a higher price. If golf is the current fad there is not much appeal in filling the store with tennis racquets. He buys golf clubs at wholesale and sells them at retail plus 10% wherever possible. We buy shares in a rising trend because we can resell them at a higher price in a few days or weeks or months. Every now and then we get an unexpected bonus on the sale. Others call it a dividend.

Here is where common usage conflicts with the correct understanding of these activities and it is shown on the right hand side of Figure 1.2. When we commonly talk about investing we include both asset income management and trading activities. We bundle the two together and this makes it very easy to fool ourselves when things go wrong.

It works like this:

- The ‘investor’ buys a dividend-paying stock at a good price and holds it for the ‘long term’. He is an asset income manager.

- The ‘investor’ buys a stock in a strong industry sector with a bright future. He pays a high price for it because he intends to sell it at some time in the future to collect the capital gain. He thinks he is investing, but in fact he is trading. He buys an item — the share — because he believes others will want to buy it from him at a later date, perhaps in the ‘long term’, for a higher price.

- The ‘investor’ buys a once-strong stock which has been in a slump for several years. He buys it because he believes the downtrend is about to end as demand for the company’s products improves, or management gets better, or for any one of a hundred reasons. He buys this bargain because he believes others will want to buy it off him at a later date, perhaps in the ‘long term’ for a higher price, so he is prepared to wait. He has no income from the asset while he waits. His profit depends entirely on capital gain. He is trading, not investing.

- The ‘investor’ buys a strongly performing stock that does not pay a dividend. It continues to rise in price for a few months, and then it rolls over into a downtrend. The downtrend continues for several years and the ‘investor’ still holds onto the stock. In fact, he might even buy some more because it is now cheaper than when he first bought it. His intention is to sell the stock at some time in the future for a higher price than he paid for it. His profit depends on the difference between his buy price and his sell price. He might believe he is an ‘investor’ because he is dealing with a well-known, high-profile, well-respected listed company, but his purpose is not different from the ‘investor’ who buys a small bio-tech company hoping to sell it for a higher price at some time in the future. Both are trading, not investing, because their reward comes from capital gain.

The activities of an asset income manager are very different from those of an ‘investor’. However, common usage of the term ‘investor’ combines and confuses asset income management with the business of buying and selling a product — listed market equities or shares. When we talk of investors in this book we are not referring to asset income managers. We are talking about ‘investors’ who aim to make a capital gain from their activity and who believe the ‘long term’ will assist them.

Take the time to re-examine your own ‘investments’. If you purchased them with the intention of selling them at a higher price in the future then this book is for you.

Trading Time and Risk

Popular opinion suggests the difference between trading and investing is also related to the time taken in each trade. Traders are short term, holding a stock for days or weeks. Investors are long term, holding a stock for months or years. Like many commonly accepted ideas in the market, these definitions are quite wrong and misleading. The difference between traders and investors is about their understanding of risk — not time. A trader may ride an uptrend for many months, but this does not make him an investor.

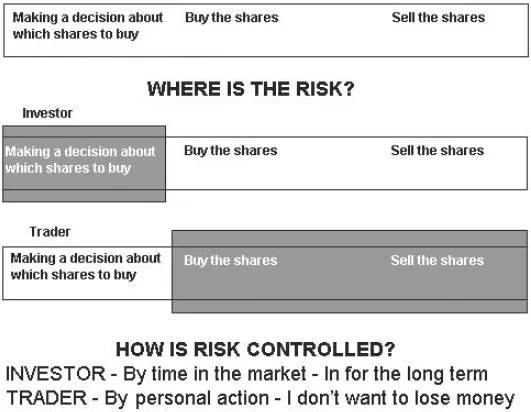

The real difference between traders and investors is in the way they approach the risk of market exposure, and is summarised in Figure 1.3. Investors usually believe the risk is mainly found prior to buying the stock. Their focus is on analysis and stock selection risk. Investors often spend a lot of time selecting the best stock. They favour fundamental research methods, looking at market share, company activities, management quality and financial reports. This research is important.

After an exhaustive analysis process the investors buy their selected stock and then largely forget about it because they believe the most difficult part of investing is in finding the right stock. The investors usually believe they have made the right choice. They are prepared to ride out any ups and downs because they believe these are minor fluctuations in the price. When the uptrend turns into a very clear downtrend they stay with the stock because they believe their analysis is sound. Larry Williams, a US trader and author, suggests investors are the biggest gamblers in the market because they make a bet and stay with it.

The trader takes a different approach. He does not abandon analysis of the stock and the company. He takes the time to research the trading opportunity. He may use the same analysis methods as the investor, or he may look for different types of analysis conclusions. The difference is not in how he selects stocks, but how he manages them once purchased.

The trader recognises the time of maximum risk is when he buys the stock. He knows the market has the power to destroy his profits, or his investment capital. He accepts this market test and he accepts the answer provided by the market. If the market does not agree with his analysis, then prices will fall.

Unfortunately if you go to some markets you might be robbed by a pickpocket. You protect yourself ...