![]()

PART I

FUNDAMENTALS

![]()

CHAPTER 1

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

1.1 OVERVIEW

This chapter provides a general introduction to the book, to latent class analysis (LCA) (e.g., Goodman, 1974a, 1974b; Lazarsfeld and Henry, 1968), and to a special version of LCA for longitudinal data, latent transition analysis (LTA) (e.g., Bye and Schechter, 1986; Langeheine, 1988). (Unless we indicate otherwise, when we discuss the latent class model in general we are referring to both LCA and LTA.) We discuss the conceptual foundation of the latent class model and show how the latent class model relates to other latent variable models. Two empirical examples are presented, both based on data on adolescent delinquency: one LCA and the other LTA. These empirical examples are discussed in very conceptual terms, with the objective of helping the reader to gain an initial feeling for these models rather than to convey any technical information. Next is an overview of the remaining chapters in the book. This chapter ends with some information about sources of empirical data used for the book’s examples, information about software that can be used for LCA and LTA, and a discussion of the additional resources that can be found on the book’s web site.

1.2 CONCEPTUAL FOUNDATION AND BRIEF HISTORY OF THE LATENT CLASS MODEL

Some phenomena in the social, behavioral, and health sciences can be represented by a model in which there are distinct subgroups, types, or categories of individuals. Many examples can be found in the scientific literature. One example is Coffman, Patrick, Palen, Rhodes, and Ventura (2007), who identified subgroups of U.S. high school seniors who had different motivations for drinking. Another example is Kessler, Stein, and Berglund (1998). Based on a sample of U.S. residents between the ages of 15 and 54 who participated in the National Comorbidity Survey (Kessler at al., 1994), Kessler et al. identified two types of social phobias. A third example is Bulik, Sullivan, and Kendler (2000), who identified six different categories of disordered eating in a sample of female twins, also U.S. residents. Each of these studies used LCA to identify subgroups in empirical data.

As the name implies, LCA is a latent variable model. Readers may be acquainted with other latent variable models: for example, factor analysis. (How LCA relates to other latent variable models is discussed in Section 1.2.1.) The term latent means that an error-free latent variable is postulated. The latent variable is not measured directly. Instead, it is measured indirectly by means of two or more observed variables. Unlike the latent variable, the observed variables are subject to error. Most statistical analysis approaches based on latent variable models attempt to separate the latent variable and measurement error.

The scientific literature has used a variety of terms for latent variables and observed variables. Latent variables are often referred to as constructs, particularly in psychology and related fields (Pedhazur and Schmelkin, 1991). In this book we sometimes refer to the observed variables as indicators of the latent variable, to emphasize their role in measurement. We also use the term item when we are referring to particular questions on data collection instruments such as questionnaires or interviews.

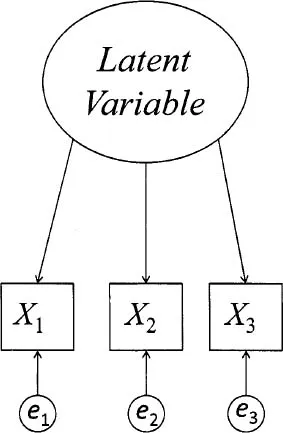

Figure 1.1 illustrates a hypothetical latent variable. In the figure the latent variable is represented by an oval. The observed indicator variables measuring the latent variable are represented by squares labeled X1, X2, and X3. The circles containing the letters e1, e2, and e3 represent the error components associated with X1, X2, and X3 respectively. There are arrows running from the latent variable to each indicator variable, as well as arrows running from each error component to each indicator variable. These arrows represent an important concept underlying all latent variable models, including LCA: The causes of the observed indicator variables are the latent variable and error. It is particularly noteworthy that the causal flow is from the latent variable to the indicator variable, not the other way around. That is, observed indicator variables measure latent variables, but the observed indicator variables do not cause the latent variables.

Figure 1.1 Latent variable with three observed variables as indicators.

In LCA each latent variable is categorical, comprised of a set of latent classes. These latent classes are measured by observed indicators. In Coffman et al. (2007) the latent variable was motivation for drinking. The latent classes consisted of one group of high school seniors motivated primarily by wanting to experiment with alcohol; a second group made up of thrill-seekers; a third group motivated primarily by the desire to relax; and a fourth group motivated by all of these reasons. Coffman et al. measured motivations for drinking using questionnaire item data from Monitoring the Future (Johnston, Bachman, and Schulenberg, 2005). In Kessler et al. (1998) the latent variable was social phobia. The latent classes were those with fears that were primarily about speaking, and those with a broader range of fears. Kessler et al. measured social phobia using interview data from the National Comorbidity Survey (Kessler et al., 1994). In Bulik et al. (2000) the latent variable was disordered eating, consisting of the following six latent classes: Shape/Weight Preoccupied; Low Weight with Binging; Low Weight Without Binging; Anorexic; Bulimic; and Binge Eating. Bulik et al. measured disordered eating based on symptoms obtained from detailed interviews.

1.2.1 LCA and other latent variable models

A number of latent variable models are in wide use in the social, behavioral, and health sciences (e.g., Bollen, 1989, 2002; Bollen and Curran, 2005; Joreskog and Sorbom, 1979; Klein, 2004; Nagin, 2005; Skrondal and Rebe-Hesketh, 2004; Von Eye and Clogg, 1994). One of the best-known is factor analysis (e.g., Gorsuch, 1983; McDonald, 1985; Thurstone, 1954). The latent class model is directly analogous to the factor analysis model. Both models posit an underlying latent variable that is measured by observed variables. The key difference between the latent class and factor analysis models lies in the nature and distribution of the latent variable. As mentioned above, in LCA the latent variable is categorical. This categorical latent variable has a multinomial distribution. By contrast, in classic factor analysis the latent variable is continuous, sometimes referred to as dimensional (Ruscio and Ruscio, 2008), and normally distributed. Ruscio and Ruscio (2008) define categorical latent variables as those in which “qualitative differences exist between groups of people or objects” and continuous (or dimensional) latent variables as those in which “people or objects differ quantitatively along one or more continua” (p. 203). In both LCA and factor analysis, the observed variables are a function of the latent variable and error, although the exact function differs in the two models. To date, considerable work has been done concerning continuous latent variables (e.g., Bollen, 1989; Joreskog and Sorbom, 1979; Klein, 2004). There has been somewhat less research on categorical latent variable models, but interest in this topic appears to be growing.

Table 1.1 shows how LCA relates to some other latent variable models for crosssectional data. As Table 1.1 shows, latent variable models can be organized according to (a) whether the latent variable is categorical or continuous, and (b) whether the indicator variables are treated as categorical or continuous. Sometimes the distinctions between the various models are a bit arbitrary, but we make them, nevertheless, to help clarify where latent class models fit in with other latent variable models and to help illustrate what kinds of models we discuss in this book. Models in which the latent variable is continuous and the indicators are treated as continuous are referred to as factor analysis. When the latent variable is continuous and the indicators are treated as categorical, this is referred to as latent trait analysis or, alternatively, item response theory (e.g., Baker and Kim, 2004; Embretson and Reise, 2000; Langeheine and Rost, 1988; Lord, 1980; Van der Linden and Hambleton, 1997). Approaches in which the latent variable is categorical and the indicators are treated as continuous are generally referred to as latent profile analysis (e.g., Gibson, 1959; Moustaki, 1996; Vermunt and Magidson, 2002), although they are sometimes referred to as latent class models. In this book, when we refer to latent class models we mean models in which the latent variable is categorical and the indicators are treated as categorical.

Table 1.1 is intended as an overview rather than a complete taxonomy of all latent variable models. Therefore, it does not mention all latent variable models. For example, there are latent variable models that treat the indicators as ordered categorical, count data, or other metrics (e.g., Bockenholt, 2001; Vermunt and Magidson, 2000).

Table 1.1 Four Different Latent Variable Models

| | Continuous Latent Variable | Cateorical Latent grariable |

| Indicators treated as continuous | Factor analysis | Latent profile analysis |

| Indicators treated as categorical | Latent trait analysis or item response theory | Latent class analysis |

1.2.2 Some historical milestones in LCA

In this section we briefly present some historical milestones in LCA. This section is intended not to be a comprehensive account of important work in LCA, merely to note some work that is particularly relevant to this book. Thus much important work is necessarily omitted. More detailed histories of LCA may be found in Goodman (2002), Langeheine (1988), and Clogg (1995).

One early major work on latent class analysis was the book by Lazarsfeld and Henry (1968). They were not the first to sugg...