eBook - ePub

Handbook of Usability Testing

How to Plan, Design, and Conduct Effective Tests

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Usability Testing

How to Plan, Design, and Conduct Effective Tests

About this book

Whether it's software, a cell phone, or a refrigerator, your customer wants - no, expects - your product to be easy to use. This fully revised handbook provides clear, step-by-step guidelines to help you test your product for usability. Completely updated with current industry best practices, it can give you that all-important marketplace advantage: products that perform the way users expect. You'll learn to recognize factors that limit usability, decide where testing should occur, set up a test plan to assess goals for your product's usability, and more.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of Usability Testing by Jeffrey Rubin,Dana Chisnell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & UI/UX Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Usability Testing: An Overview

Chapter 1: What Makes Something Usable?

Chapter 2: What Is Usability Testing?

Chapter 3: When Should You Test?

Chapter 4: Skills for Test Moderators

Chapter 1

What Makes Something Usable?

What makes a product or service usable?

Usability is a quality that many products possess, but many, many more lack. There are historical, cultural, organizational, monetary, and other reasons for this, which are beyond the scope of this book. Fortunately, however, there are customary and reliable methods for assessing where design contributes to usability and where it does not, and for judging what changes to make to designs so a product can be usable enough to survive or even thrive in the marketplace.

It can seem hard to know what makes something usable because unless you have a breakthrough usability paradigm that actually drives sales (Apple's iPod comes to mind), usability is only an issue when it is lacking or absent. Imagine a customer trying to buy something from your company's e-commerce web site. The inner dialogue they may be having with the site might sound like this: I can't find what I'm looking for. Okay, I have found what I'm looking for, but I can't tell how much it costs. Is it in stock? Can it be shipped to where I need it to go? Is shipping free if I spend this much? Nearly everyone who has ever tried to purchase something on a web site has encountered issues like these.

It is easy to pick on web sites (after all there are so very many of them), but there are myriad other situations where people encounter products and services that are difficult to use every day. Do you know how to use all of the features on your alarm clock, phone, or DVR? When you contact a vendor, how easy is it to know what to choose in their voice-based menu of options?

What Do We Mean by “Usable”?

In large part, what makes something usable is the absence of frustration in using it. As we lay out the process and method for conducting usability testing in this book, we will rely on this definition of “usability;” when a product or service is truly usable, the user can do what he or she wants to do the way he or she expects to be able to do it, without hindrance, hesitation, or questions.

But before we get into defining and exploring usability testing, let's talk a bit more about the concept of usability and its attributes. To be usable, a product or service should be useful, efficient, effective, satisfying, learnable, and accessible.

Usefulness concerns the degree to which a product enables a user to achieve his or her goals, and is an assessment of the user's willingness to use the product at all. Without that motivation, other measures make no sense, because the product will just sit on the shelf. If a system is easy to use, easy to learn, and even satisfying to use, but does not achieve the specific goals of a specific user, it will not be used even if it is given away for free. Interestingly enough, usefulness is probably the element that is most often overlooked during experiments and studies in the lab.

In the early stages of product development, it is up to the marketing team to ascertain what product or system features are desirable and necessary before other elements of usability are even considered. Lacking that, the development team is hard-pressed to take the user's point of view and will simply guess or, even worse, use themselves as the user model. This is very often where a system-oriented design takes hold.

Efficiency is the quickness with which the user's goal can be accomplished accurately and completely and is usually a measure of time. For example, you might set a usability testing benchmark that says “95 percent of all users will be able to load the software within 10 minutes.”

Effectiveness refers to the extent to which the product behaves in the way that users expect it to and the ease with which users can use it to do what they intend. This is usually measured quantitatively with error rate. Your usability testing measure for effectiveness, like that for efficiency, should be tied to some percentage of total users. Extending the example from efficiency, the benchmark might be expressed as “95 percent of all users will be able to load the software correctly on the first attempt.”

Learnability is a part of effectiveness and has to do with the user's ability to operate the system to some defined level of competence after some predetermined amount and period of training (which may be no time at all). It can also refer to the ability of infrequent users to relearn the system after periods of inactivity.

Satisfaction refers to the user's perceptions, feelings, and opinions of the product, usually captured through both written and oral questioning. Users are more likely to perform well on a product that meets their needs and provides satisfaction than one that does not. Typically, users are asked to rate and rank products that they try, and this can often reveal causes and reasons for problems that occur.

Usability goals and objectives are typically defined in measurable terms of one or more of these attributes. However, let us caution that making a product usable is never simply the ability to generate numbers about usage and satisfaction. While the numbers can tell us whether a product “works” or not, there is a distinctive qualitative element to how usable something is as well, which is hard to capture with numbers and is difficult to pin down. It has to do with how one interprets the data in order to know how to fix a problem because the behavioral data tells you why there is a problem. Any doctor can measure a patient's vital signs, such as blood pressure and pulse rate. But interpreting those numbers and recommending the appropriate course of action for a specific patient is the true value of the physician. Judging the several possible alternative causes of a design problem, and knowing which are especially likely in a particular case, often means looking beyond individual data points in order to design effective treatment. There exist these little subtleties that evade the untrained eye.

Accessibility and usability are siblings. In the broadest sense, accessibility is about having access to the products needed to accomplish a goal. But in this book when we talk about accessibility, we are looking at what makes products usable by people who have disabilities. Making a product usable for people with disabilities—or who are in special contexts, or both—almost always benefits people who do not have disabilities. Considering accessibility for people with disabilities can clarify and simplify design for people who face temporary limitations (for example, injury) or situational ones (such as divided attention or bad environmental conditions, such as bright light or not enough light). There are many tools and sets of guidelines available to assist you in making accessible designs. (We include pointers to accessibility resources on the web site that accompanies this book (see www.wiley.com/go/usabilitytesting.com for more information.) You should acquaint yourself with accessibility best practices so that you can implement them in your organization's user-centered design process along with usability testing and other methods.

Making things more usable and accessible is part of the larger discipline of user-centered design (UCD), which encompasses a number of methods and techniques that we will talk about later in this chapter. In turn, user-centered design rolls up into an even larger, more holistic concept called experience design. Customers may be able to complete the purchase process on your web site, but how does that mesh with what happens when the product is delivered, maintained, serviced, and possibly returned? What does your organization do to support the research and decision-making process leading up to the purchase? All of these figure in to experience design.

Which brings us back to usability.

True usability is invisible. If something is going well, you don't notice it. If the temperature in a room is comfortable, no one complains. But usability in products happens along a continuum. How usable is your product? Could it be more usable even though users can accomplish their goals? Is it worth improving?

Most usability professionals spend most of their time working on eliminating design problems, trying to minimize frustration for users. This is a laudable goal! But know that it is a difficult one to attain for every user of your product. And it affects only a small part of the user's experience of accomplishing a goal. And, though there are quantitative approaches to testing the usability of products, it is impossible to measure the usability of something. You can only measure how unusable it is: how many problems people have using something, what the problems are and why.

By incorporating evaluation methods such as usability testing throughout an iterative design process, it is possible to make products and services that are useful and usable, and possibly even delightful.

What Makes Something Less Usable?

Why are so many high-tech products so hard to use?

In this section, we explore this question, discuss why the situation exists, and examine the overall antidote to this problem. Many of the examples in this book involve not only consumer hardware, software, and web sites but also documentation such as user's guides and embedded assistance such as on-screen instructions and error messages. The methods in this book also work for appliances such as music players, cell phones, and game consoles. Even products, such as the control panel for an ultrasound machine or the user manual for a digital camera, fall within the scope of this book.

Five Reasons Why Products Are Hard to Use

For those of you who currently work in the product development arena, as engineers, user-interface designers, technical communicators, training specialists, or managers in these disciplines, it seems likely that several of the reasons for the development of hard-to-use products and systems will sound painfully familiar.

- Development focuses on the machine or system.

- Target audiences change and adapt.

- Designing usable products is difficult.

- Team specialists don't always work in integrated ways.

- Design and implementation don't always match.

Reason 1: Development Focuses on the Machine or System

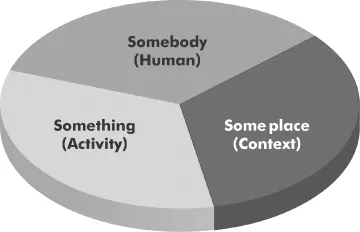

During design and development of the product, the emphasis and focus may have been on the machine or system, not on the person who is the ultimate end user. The general model of human performance shown in Figure 1.1 helps to clarify this point.

Figure 1.1 Bailey's Human Performance Model

There are three major components to consider in any type of human performance situation as shown in Bailey's Human performance model.

- The human

- The context

- The activity

Because the development of a system or product is an attempt to improve human performance in some area, designers should consider these three components during the design process. All three affect the final outcome of how well humans ultimately perform. Unfortunately, of these three components, designers, engineers, and programmers have traditionally placed the greatest emphasis on the activity component, and much less emphasis on the human and the context components. The relationship of the three components to each other has also been neglected. There are several explanations for this unbalanced approach:

- There has been an underlying assumption that because humans are so inherently flexible and adaptable, it is easier to let them adapt themselves to the machine, rather than vice versa.

- Developers traditionally have been more comfortable working with the seemingly “black and white,” scientific, concrete issues associated with systems, than with the more gray, muddled, ambiguous issues associated with human beings.

- Developers have historically been hired and rewarded not for their interpersonal, “people” skills but for their ability to solve technical problems.

- The most important factor leading to the neglect of human needs has been that in the past, designers were developing products for end users who were much like themselves. There was simply no reason to study such a familiar colleague. That leads us to the next point.

Reason 2: Target Audiences Expand and Adapt

As technology has penetrated the mainstream consumer market, the target audience has expanded and continues to change dramatically. Development organizations have been slow to react to this evolution.

The original users of computer-based products were enthusiasts (also known as early adopters) possessing expert knowledge of computers and mechanical devices, a love of technology, the desire to tinker, and pride in their ability to troubleshoot and repair any problem. Developers of these products shared similar characteristics. In essence, users and developers of these systems were one and the same. Because of this similarity, the developers practiced “next-bench” design, a method of designing for the user who is literally sitting one bench away in the development lab. Not surprisingly, this approach met with relative success, and users rarely if ever complained about difficulties.

Why would they complain? Much of their joy in using the product was the amount of tinkering and fiddling required to make it work, and enthusiast users took immense pride in their abilities to make these complicated products function. Consequently, a “machine-oriented” or “system-oriented” approach met with little resistance and became the development norm.

Today, however, all that has changed dramatically. Users are apt to have little technical knowledge of computers and mechanical devices, little patience for tinkering with the product just purchased, and completely different expectations from those of the designer. More important, today's user is not even remotely comparable to the designer in skill set, aptitude, expectation, or almost any attribute that is relevant to the design process. Where in the past, companies mig...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the Authors

- Credits

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Part I: Usability Testing: An Overview

- Part II: The Process for Conducting a Test

- Part III: Advanced Techniques

- Afterword

- Index