- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Investing in Renewable Energy puts the depletion of finite resources such as oil, natural gas, and coal in perspective, and discusses how renewable energy solutions–from solar and wind to geothermal and biofuels–will usher in a new generation of wealth for investors and a new way of life for everyone. With this book, you'll discover various renewable energy technologies that are at the forefront of transitioning our energy economy, and learn how to profit from next-generation renewable energy projects and companies that are poised to take over where fossil fuels will leave off.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Investing in Renewable Energy by Jeff Siegel,Chris Nelder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Investments & Securities. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

TRANSITIONING TO THE NEW ENERGY ECONOMY

“I’d put my money on the sun and solar energy. What a source of power! I hope we don’t have to wait until oil and coal run out before we tackle that.”

—THOMAS EDISON

CHAPTER 1

THE GLOBAL ENERGY MELTDOWN

The world is now facing its most serious challenge ever. The name of that challenge is peak energy.

If decisive and immediate action is not taken, peak energy could prove to be a crisis more devastating than world wars, more intractable than plagues, and more disruptive than crop failure. We’re talking about a crisis of epic proportions that will change everything. And rest assured it will not discriminate. Conservative or liberal, black or white, rich or poor, this will be a crisis of equal-opportunity devastation. That may sound hyperbolic to you now, but by the end of this chapter, you will understand why we say it.

Everything we do depends on some form of energy. Our entire way of life, and all of our economic projections, are built on the assumption that there will always be more energy when we want it. But global energy depletion has already begun, although few have realized it.

You’re one of the lucky ones, because after reading this book, you will understand both the challenge of peak energy and some of the solutions early in the game—allowing you the opportunity to be well-positioned to not only profit from the renewable energy revolution that is already under way, but to thrive.

By the time you’ve completed this chapter, you will have a full understanding of what peak energy is, how it affects the future of the entire global economy, and why it is imperative that this challenge of peak energy is met head-on with renewable energy solutions. This will ultimately lead you to profits via the companies that are providing the solutions both in the near-term and well into the future.

PEAK ENERGY

Before we begin discussing the particulars of peak oil, gas, coal, and uranium, we must first discuss what we mean when we use the term peak energy.

The production of any finite resource generally follows a bell curve shape. You start by producing a little, and then increase it over time; then you reach a peak production rate, after which it declines to make the back side of the curve. Between now and 2025, we could see the peak of every single one of our finite fuel resources. But why is the peak important? Because after the peak, we witness the rapid decline of these fuels, leaving us vulnerable to what could amount to the biggest disruption the global economy has ever witnessed. This would be a disruption that could spark an international crisis of epic proportions.

Peak Oil

The first resource that will peak is oil, which is also our most important and valuable fuel resource. We have an entire chapter devoted to oil—Chapter 8—so we will merely summarize here. Here are some simple facts about peak oil:

• The world’s largest oil reservoirs are mature.

• Approximately three-quarters of the world’s current oil production is from fields that were discovered prior to 1970, which are past their peaks and beginning their declines.1

• Much of the remaining quarter comes from fields that are 10 to 15 years old.

• New fields are diminishing in number and size every year, and this trend has held for over a decade.2

Overall, the oil fields we rely on to meet demand are old, and their production is shrinking, thereby bringing the oil industry closer to the peak and our entire global economy closer to the brink of catastrophe. Because when these fields dry up, so does everything else. And unfortunately, while today’s oil fields are struggling at this very moment to keep pace with demand, new field discoveries are diminishing.

Before you can tap a reservoir, you must discover it. Here, too, the picture is clear: The world passed the peak of oil discovery in the early 1960s, and we now find only about one barrel of oil for every three we produce.3 The fields we’re discovering now are smaller, and in more remote and geographically challenging locations, making them far more expensive to produce. And the new oil is of lesser quality: less light sweet crude, and more heavy sour grades. These trends have held firmly for about four decades, despite the latest and greatest technology, and despite increasingly intensive drilling and exploration efforts.

This should be no surprise to anyone. It’s the nature of resource exploitation that we use the best, most abundant and lowest-cost resources first, then move on to smaller resources of lower quality, which are harder to produce.

Global conventional oil production peaked in 2005. For “all liquids,” including unconventional oil, the peak of global production will likely be around 2010.

With a little less than half the world’s total yet to produce, which will increasingly come from ever-smaller reservoirs with less desirable characteristics, peak oil is not about “running out of oil,” but rather running out of cheap oil.

The outlook for oil exports, on which the United States is dependent for over two-thirds of its petroleum usage, is even worse. Global exports have been on a plateau since 2004. This poses a firm limit to economic growth.

In sum, demand for oil is still increasing, while supply is decreasing; the absolute peak of oil production is probably within the next two years; and net importers like the United States are not going to be able to maintain current levels of imports, let alone increase them. This is a very serious situation, because without enough imports to meet demand, we simply cannot function. We will find it increasingly difficult to transport food, medicine, and clothing; to fuel our planes, trains, automobiles, and cargo ships; to provide heat in the winter and cooling in the summer; and to manufacture plastics and other goods that rely on petroleum as a key ingredient.

While the world’s top energy data agencies have all commented on the threat of peak oil, along with many of the leaders of the world’s top energy producers, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) may have said it best:

[T]he consequences of a peak and permanent decline in oil production could be even more prolonged and severe than those of past oil supply shocks. Because the decline would be neither temporary nor reversible, the effects would continue until alternative transportation technologies to displace oil became available in sufficient quantities at comparable costs.4

Even so, peak oil is just the first hard shock of the energy crisis that will soon be unfolding. Right after peak oil, we will have peak gas.

Peak Gas

In many ways, the story of natural gas is similar to that of oil. It has a bell-shaped production curve (although compared to oil, it hits a longer production plateau, and drops off much faster on the back side), and the peak occurs at about the halfway point.

Like oil, new gas wells are tapping smaller and less productive resources every year, indicating that the best prospects have already been exploited and that we’re now relying on “infill drilling” and unconventional sources, such as tight sands gas, coalbed methane, and resources that are deeper and more remote.

Like oil, the largest deposits of gas are few in number and highly concentrated. Just three countries hold 58 percent of global gas reserves: Russia, Iran, and Qatar. All other gas provinces have 4 percent or less.5

And like oil, there is the quality issue. It appears that we have already burned through the best and cheapest natural gas—the high-energy-content methane that comes out of the ground easily at a high flow rate. We’re now getting down to smaller deposits of “stranded gas” and the last dregs of mature gas fields, and producing gas that has a lower energy content.

Assuming that world economic growth continues, that estimates of conventional reserves are more or less correct, and that there will not be an unexpected spike in unconventional gas, the world will hit a short gas plateau by 2020, and by around 2025 will go into decline.6

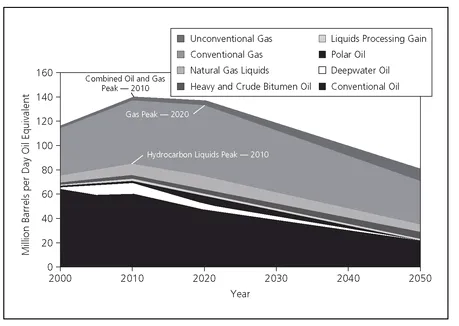

To illustrate our argument, consider the forecast for natural gas and oil combined, from Dr. Colin Campbell of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil (ASPO), which is shown in Figure 1.1.

However, the local outlook for natural gas is far more important than the global outlook. Natural gas production is mostly a landlocked business, because it’s difficult to store and expensive to liquefy for transport. In the United States, we import only 19 percent of the natural gas we use, of which 86 percent is transported by pipeline from Canada and Mexico, both of which are past their peaks. Imports from Canada account for about 17 percent of our total gas consumption,7 but Canada may have as little as seven years’ worth of natural gas reserves left.8

Because it’s difficult to store, there is little storage or reserve capacity in our nation’s web of gas pipelines and storage facilities. In the United States, we have only about a 50-day supply of working storage of natural gas.9 There isn’t much cushion in the system; everything operates on a just-in-time inventory basis, including market pricing.

FIGURE 1.1 Campbell’s (2003) Forecast of World Oil and Gas Production

Sources: Data: C.J. Campbell and Anders Sivertsson, 2003; chart: David J. Hughes slide deck, “Can Energy Supply Meet Forecast World Demand?,” November 3, 2004.

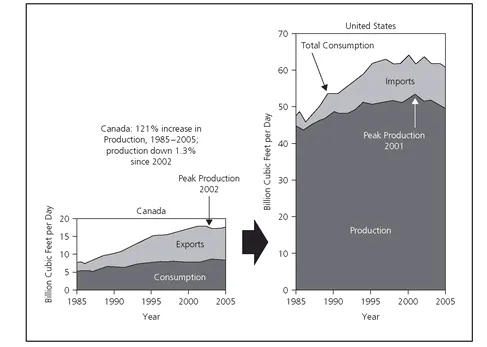

Therefore, our main concern with gas is the domestic production peak. North America reached its peak of gas production in 2002, and has been declining ever since—the inevitable result of mature gas basins reaching the end of their productive lives.10 (See Figure 1.2.)

The onset of the U.S. production peak was in 2001, and production is now declining at the rate of about 1.7 percent per year—far below the projection of the Energy Information Administration, as shown in Figure 1.3.

The declining plateau of production has held despite the application of the world’s most advanced technology, and a tripling of producing gas wells since 1971, from approximately 100,000 to more than 300,000. (See Figure 1.4.)

The same is true for Canada, where they’ve been drilling more than ever, but production is still declining. Consequently, in recent years, gas rigs have been leaving Canada, and going to locations elsewhere in the world where rental fees are higher.

FIGURE 1.2 North American Gas Production, 1985-2005

Source: J. David Hughes, “Natural Gas in North America: Should We Be Worried?,” October 26, 2006, http://www.aspo-usa.com/fall2006/presentations/pdf/Hughes_D_NatGas_Boston_2006.pdf.

In North America, the best and cheapest natural gas at high flow rates is gone. For the United States, this is again a very serious situation. Current supply-and-demand forecasts indicate that a shortfall in natural gas supply is looming, possibly by as much as 11 trillion cubic feet (tcf) per year by 2025, or about half of U.S. current usage of 22 tcf/year.

When we passed the North American gas peak, as seen in Figure 1.5, the price of gas imports skyrocketed. Yet demand has continued to increase, in part due to increased demand for grid power, but also in part due to switching over to gas from petroleum, which has increased in price even more rapidly than gas. Now we’re needing more imports every year, but getting about the same amounts, and payin...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- PREFACE

- PART I - TRANSITIONING TO THE NEW ENERGY ECONOMY

- PART II - THE END OF OIL

- PART III - THE SCIENCE AND PROFITABILITY OF CLIMATE CHANGE

- CONCLUSION

- NOTES

- ABOUT THE AUTHORS

- INDEX