![]()

SECTION III

Optimizing Talent

“We believe our fundamental strength lies in our people.”

—Sam Johnson, S.C. Johnson

Few would argue with Sam Johnson’s observation that people are, or at least can be, the cornerstone strength of any organization. They can also be a strategic vulnerability. Talent that is squandered creates a competitive disadvantage as fast as shoddy products or service quality. Manage talent to yield optimal value and you are on your way to becoming a fiercely competitive enterprise.

From an organizational viewpoint, talent optimization means higher performance, better quality, more satisfied customers or clients, fewer accidents, and greater profitability. If your talent optimization is better than that of your competitors, it means that you are investing less in labor costs to achieve high performance, a key factor in a tightening world of competition and cost management.

From an individual’s perspective, maximizing potential means becoming the best you can be—better skills and experiences, achieving new levels of accomplishment, building strong relationships, and increasing personal value. And that means increasing your value to your current or potential future employers. Individual talent optimization is not just about money or prestige; it is about accelerating progress toward your life goals.

As David Ulrich1 has pointed out, “No matter how interesting or valuable an activity may seem to those doing it, if those who receive the output of that activity don’t find it of value to them, continuing the activity cannot be justified. Value is the great equalizer, and as the planet becomes more crowded and organizations compete for increasingly scarce resources, value will be the factor that differentiates those who gain or lose in the quest toward their goals—personal or organizational.”

People Equity and Talent Optimization

People Equity is a helpful framework to use in thinking about optimizing both organizational and individual value. In this section, we will look at the role of People Equity in helping to guide decisions that will optimize workforce performance and worker fulfillment.

People Equity plays a central role in assessing and guiding talent optimization in several key ways.

1. Immediately following the hire of a new person, People Equity provides a way to track talent development in the fragile, formative employment period that is decisive in determining future performance.

2. People Equity and its nine Drivers and Enablers provide a framework for understanding the major drivers of workforce optimization and when coupled with an appropriate measurement of these factors, they provide an ongoing way to track how well talent is being used.

3. By understanding the drivers and enablers of Alignment, Capabilities, and Engagement, leaders can effectively target limited resources to the right root causes that will most improve People Equity and by extension key business results.

Let us focus for a moment on the alternative ACE futures that we have discussed earlier. Remember, in our examination of hundreds of organizations and thousands of work units, we find ACE scores that vary from winning cultures with scores over 90 to ones that score below 20.

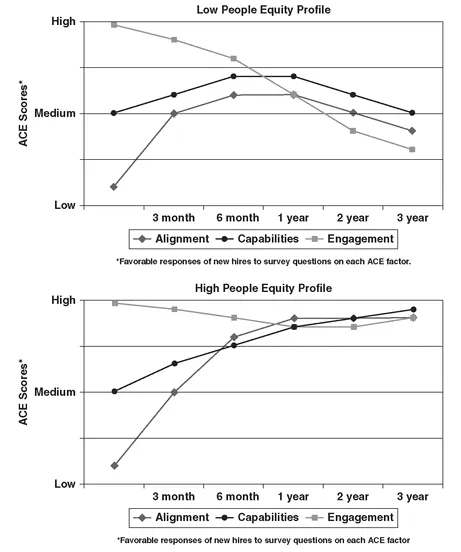

Figure III.1 shows two talent optimization futures that we encounter every day in our organizational assessments. The profile on the bottom continues the growth of ACE from the onboarding period while the one on the top shows a pattern of an organization that squanders its human capital.

The low People Equity profile on the top is typically fraught with conflict, low productivity, and employees who either physically leave or mentally leave their employer. Our experience suggests that it is unfortunately more often the top performers who leave while the performance indigent remain with the organization.

In low People Equity firms, Alignment never reaches high levels; in fact, it generally reaches middle levels and then recedes slowly. This often happens because the organization stops realigning. It fails to communicate changes in the strategy and new priorities, to modify or change measures and targets required of new market conditions, or to rethink rewards that reinforce old behaviors. In some organizations, longer-tenured employees are more out of touch than new hires.

The future Capabilities curve can veer in different directions, as you can see from Figure III.1. For high People Equity firms, Capabilities continue to grow. They are adjusted to remain relevant to new or changing customer expectations. Employees are encouraged to develop their potential. Individuals are often trained across knowledge or skills areas. In these learning organizations, the Capabilities dimension grows and grows, often with scores into the 90s.2

For low People Equity organizations, the initial rapid growth in Capabilities scores often resembles a roller coaster ride. Veteran workers often think that they have already been trained; training is for the new people. Employees may tout skills that are no longer relevant. The skills of computer programmers, for example, can become obsolete in as short as one or two years when deep expertise in one technology has been supplanted with the next technology generation. Research suggests that many don’t make the change and ultimately look for other work. Another study found that some managerial skills become 50 percent obsolete within five years.3

FIGURE III.1 High and Low People Equity Profiles

Still another profile that we frequently find in these low Capabilities units is talent that lacks tools or resources to meet customer expectations. The talent is being choked off. It may seem absurd that an organization would do this, but the resourcing decisions, behaviors, and subsequent consequences are often indirect, occurring over many years of making small choices that suboptimize the Capabilities needed to meet changing customer requirements. While at times this is a conscious decision for budgetary or strategic reasons—for example, a cash cow unit that the organization is milking until disposal—more often the change is incremental, often going unnoticed because of insufficient measurement tools to track the impact.

And finally, in high Engagement organizations, employees are exuberant about the organization, its mission, and their roles. They are willing to advocate to others to come join or invest in their organization. They exhibit high loyalty to and identification with the organization and their unit. The low Engagement profile is often fraught with employees who do the minimum, would not encourage others to follow their plight, and are only as loyal as their pensions and compensation require.

Let’s now take a look at how each of the three ACE factors helps to optimize workforce performance and personal fulfillment.

![]()

6

Aligning Strategy, Culture, and Talent1

“If the CEO is going in one direction, and employees are going in another, that’s a serious problem.”

—Connie Rank-Smith, Jewelers Mutual Insurance Company and HR Certification Institute

In the 1970s, Alignment was a major concern for me and thousands of other drivers escaping for a weekend to Tijuana, Mexico. The road to Tijuana was pocked by hundreds of potholes that could swallow whole tires, leaving only two strategies: drive excruciatingly slowly while maneuvering circuitously around this moonscape, or step on the gas and hope to hydroplane over the impediments. Neither really worked, as evidenced by the smiley faces on mechanics in the vast number of auto alignment and body shops that dotted the entrance to Tijuana.

Alignment is a flock of birds or a squadron of planes flying in a perfect V formation, or a team of rowers moving surely and swiftly along a lake’s surface. Within an organizational context, “alignment is focus,” as one of our CEO interviewees put it. It implies that from top to bottom everything is connected in the most effective and efficient way possible so that there is maximal output using the least amount of input. In this chapter, we focus more on the role of Alignment in optimizing employee performance and allowing employees to become more successful.

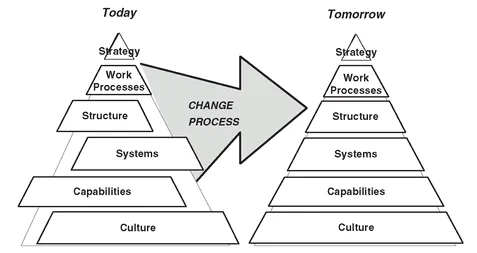

In our strategy work, we advise clients to follow a golden rule: Once you have chosen your strategic goals and customers2—those to whom your products and services will add value—the organization must have its work processes, structures, systems, capabilities, and culture aligned with that objective (see Figure 6.1). From a talent standpoint that means having behaviors that are riveted on those high value-added tasks and processes needed to serve those customers and achieve the organizational goals.

While it is a generally accepted truism that alignment is crucial to business success, there are many forces at work that cause organizations to limp along, seriously misaligned. Some misalignments are brought on by a merger. When Hewlett-Packard (HP) merged with Compaq, for example, there were clear misalignments between the cultures—HP had a long history of research and innovation primacy and Compaq was better noted for excellence in marketing. These differences in values and priorities led to the many reported conflicts of the two cultures: battles over product selection, product features, and benefits. Misaligned roles, priorities, and behaviors within the organization, coupled with serious misalignments of investment goals and strategic priorities within the HP Board,3 led to stalemates that delayed the organization in achieving its objectives.

Misalignment is often an insidious phenomenon. It typically comes about after years of poor organizational posture—creeping role scope, processes that have not adapted to new customer requirements, fuzzy strategies and priorities, or gradual service slippage. Misalignments can grow unchecked for months or years, until some traumatic event occurs—a major recession, a merger or restructuring, loss of major customers, or an internal stakeholder group that outsources services.

FIGURE 6.1 Creating Alignment

Misaligned values are especially subversive and have a way of going undetected at the top of the organization, though those at ground level often know or at least suspect what’s really happening. Enter Enron, Tyco and, more recently, just about any of the Wall Street financial firms.

McDonald’s, by contrast, provides an example of a tightly aligned organization. In the late 1990s, McDonald’s tried to shake off unprofitable growth using a number of strategies that ultimately did not succeed. When James R. Cantalupo returned from retirement after McDonald’s same-store sales hit rock bottom in 2002, he immediately focused on Alignment. He helped McDonald’s launch its “Plan to Win,” a playbook that aligns people, products, place, price, and promotion. Within a short time, employees at all levels had clear guidance for prioritizing their actions and resources. By studying the customer more effectively, and aligning company practices with the marketplace, everyone in the company was able “to focus on quality s...