![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

“Every cubic inch of space is a miracle.”

WALT WHITMAN (Leaves of Grass, “Miracles”)

WHAT THIS BOOK IS ABOUT

This book has a very specific focus: the space planning of individual rooms in homes. Many current publications are available that offer an overview of the principles of residential design combined with information about materials, finishes, and furnishings. Also available are beautiful books that provide lavish photographs and descriptions of residential design projects. Unlike those books, this one is meant to serve as a primer on space planning for major rooms/spaces in a home, and to offer related information regarding codes, mechanical and electrical systems, and a variety of additional factors that impact each type of room/space. In addition, this book includes information about accessible design in each chapter in order to provide a cohesive view of residential accessibility.

This book is meant to serve as a reference for use in the design process, and as an aid in teaching and understanding the planning of residential spaces. For purposes of clarity, most chapters follow a similar format, starting with an overview of the particular room or space and related issues of accessibility, followed with information about room-specific furnishings and appliances. Chapters continue with information about sizes and clearances, organizational flow, related codes and constraints, and issues regarding electrical, mechanical, and plumbing. At the end of each chapter, basic information is provided about lighting the specific room.

This book describes the minimum requirements for specific spaces and rooms so that students and designers can get a sense of the amount of space that is minimally necessary in order for rooms to function usefully. Examples of larger spaces are also given, but at its heart, this book is intended to show students how to use space wisely and make good use of space throughout the dwelling. Put another way: The book is about meeting the minimum standards required to create spaces that work functionally. Such minimum standards are dictated by building codes and manufacturers’ recommendations, and/or reflect good design practice. With clear knowledge about minimums, designers and students of design can learn when it is appropriate to exceed such standards for a variety of reasons that reflect specific project criteria based upon clients needs, budget, site, and other constraints.

This book is meant as an introduction to the topics covered with the intention of getting the reader comfortable with basic concepts so that he or she might move forward in design education or on to additional research in certain areas. To that end, an annotated bibliography section is provided at the end of each chapter. Thinking of the information provided in each chapter as basic building blocks that allow for the discovery of the basic issues involved is a helpful approach to this book. We state this because there is much that goes into the design of a dwelling that is not covered in this book; our intent is to focus on the use and design of individual rooms (again, a building-block approach) so that the reader will have the core information required to understand the design of these individual spaces. See Figure 1-1.

This building-block or basic informational approach may bring up questions about the role of the interior designer versus the role of the architect. Clearly, the design of the totality of the structure is the role of the architect (or engineer); however, in many cases, the interior designer is taking an increasingly larger role in the design of rooms and spaces. Interior designers engaged in renovation work can take a lead role in the design of the interior architecture of a space, with a significant hand in the design of a room or many rooms.This is in contrast to notions of the interior designer as the person in charge of materials and furnishings selections only.

Home renovation and remodeling continues to be a multibillion-dollar industry providing continuing work for interior designers, architects, builders, and others in the construction trades. Home remodeling and improvements reached a record of $275 billion in 2005, with industry experts predicting continued growth for the next several years. The most common home remodeling jobs continue to be kitchen and bathroom projects. Readers will note that the detailed kitchen and bathroom information contained in this book is applicable to remodeling as well as new construction.

Figure 1-1 This book covers the design of houses using a room-by-room approach as an aid in understanding the use and design of each room.

In new custom-home design, interior designers may take on a variety of roles from materials and furnishings selection to the design of the interior architecture of the dwelling. New-home construction has also shown continued strength, with a decade of incredibly strong sales, providing continued work for those in design, construction, and related industries. The authors believe that interior designers and design students must be well versed in the aspects of residential design covered in this book.

AN OVERVIEW: QUALITY AND QUANTITY

Readers may note that throughout the book, the authors mention the evolution of the use of rooms, room sizes, and growth of the overall size of the American home. It’s worth noting that the authors have a bias toward careful consideration of the quality of design rather than the quantity of space in a given home. We hope to make clear that the successful design of space requires careful consideration of the real needs of clients measured against budgetary, code, climate, and site restrictions—all of which require careful development of a project program prior to the beginning of the actual design of the project.

The last hundred years have brought dramatic changes related to the public perception of the design, furnishing, and size of the American house. According to the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), the “typical” American house built in 1900 was between 700 and 1200 square feet, with two or three bedrooms and one or no bathrooms (2006). The average home built in 1950 was 983 square feet, with 66 percent of homes containing 2 bedrooms or fewer. These earlier homes are quite a contrast to the 2349-square-foot average found in new single-family homes sold in 2004. A majority of these new homes (those built since 2004) have three or four bedrooms, two and one-half bathrooms or more, with at least one fireplace. A visual representation of the ever-expanding North American home can be found in Figure 1-2.

Interestingly, family size has decreased in this period to the point where the average American household size in 2004 was 2.57 persons-in contrast to 3.67 in 1940 (according to the U.S. Census). Based on a review of available figures, new homes are larger than ever, and yet they house fewer people per building than houses held, on average, in the past. The authors argue that a larger house is not necessarily a better house, and that designing a house that works well on a functional level is more important than mere size in creating a useful and pleasant environment. Additionally, large single-family homes are currently out of the financial reach of many citizens and are seen by some as wasteful in a time when issues of sustainability are increasingly engaging the national consciousness.

Figure 1-2 The average new home in the United States has grown in size over the last 50 years—despite the fact that family size has grown smaller. However, larger is not necessarily better, and well-planned spaces need not be excessively large. Given land and construction costs, as well as environmental concerns, smaller, well-designed houses may be a future trend. Numbers for square footage shown do not include garage spaces.

Consideration of housing size and use of related resources is not unique to this publication. Architect Sarah Susanka’s book The Not So Big House has proven very popular, has helped many people to consider quality over quantity of space, and has certainly had an impact on the design of many homes (1998). A Pattern Language, by Christopher Alexander and colleagues, an earlier book and one considered seminal by many, has at its core the notion that spaces should be designed for the way people really live and that good design can be accessible for all (1977).

The notion of seeking quality of design, rather than quantity of space, is shared by many, and yet larger and larger houses continue to be built to house very small family groups. This dichotomy suggests that two opposing popular views of space exist. Although the architect Phillip Johnson was once quoted as saying “architecture is the art of wasting space,” clearly that was a bit tongue-incheek, and we concur more with Walt Whitman’s notion that “Every cubic inch of space is a miracle”—or should be.

HUMAN BEHAVIOR AND HOUSING

Environmental designers—including interior designers—benefit from gaining an understanding of human behavior as it relates to privacy, territoriality, and other issues related to the built environment studied by social scientists. Privacy can be defined as having to do with the ability to control our interactions with others. According to Jon Lang: “The ability of the layout of the environment to afford privacy through territorial control is important because it allows the fulfillment of some basic human needs” (1987). Lang goes on to state that the single-family detached home “provides a clear hierarchy of territories from public to private.”

Lang also states that “differences in the need for privacy are partially attributable to social group attitudes.” He continues, “Norms of privacy for any group represent adaptation to what they can afford within the socioeconomic system of which they are a part.” From Lang’s comments we can learn that the need for privacy is consistent but varies based on culture and socioeconomic status.

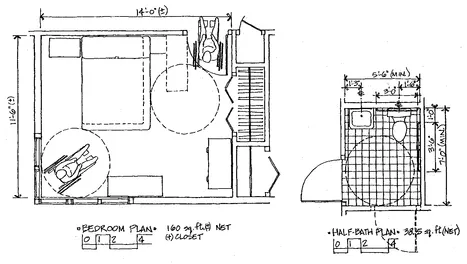

The notion of territory is closely linked to privacy in terms of human behavior. There is a range of theories about the exact name and number of territories within the home. One, developed by Claire Cooper, describes the house as divided into two components: the intimate interior and the public exterior (1967). Interestingly, Cooper (now Cooper Marcus) later wrote House as a Mirror of Self: Exploring the Deeper Meaning of Home (1995), which traces the psychology of the relationship we have with the physical environment of our homes, and in which she refers to work being done by Rachel Sebba and Arza Churchman in studying territories within the home. Sebba and Churchman have identified areas within the home as those used by the whole family, those belonging to a subgroup (such as siblings or parents), and those belonging to an individual, such as a bedroom or a portion of a room or bed (1986). Figures 1-3a and 1-3b illustrate various theoretical approaches to territory and privacy.

The term defensible space, coined by Oscar Newman, refers to “a range of mechanisms—real and symbolic barriers . . . that combine to bring an environment under the control of its residents.” Defensible space as described by Newman includes public, semi-public, semi-private, and private territories (1972).

For the most part, Newman’s public spaces, such as streets and sidewalks, are those not possessed by any individual. Semi-public spaces include those areas that may be publicly owned but are cared for by homeowners such as planted parkways adjacent to sidewalks. Semi-private spaces can include yards or spaces owned in association (some theoreticians include porches and foyers in this category). Private territory is the interior of one’s home or fenced areas within a yard, or, for example, the interior of a student’s dorm room.

Newman’s notions of defensible space and related territories have significant implications for planners, architects, and interior designers because taking them into account in designing homes can help to create spaces in which residents feel safe and have a genuine control over their immediate environment. See Figures 1-3a and 1-3b.

Figure 1-3a An illustration of territories as identified by theoreticians. Cooper identifie...