![]()

PART I

The Business

![]()

1

Extraordinary Markets

The euphoria of the equity and debt markets that caused investment banks like Bear Stearns, Merrill Lynch, and others to take massive proprietary and operational risks is gone. These risky assets were taken on leverage and as a result, the five major independent investment banks have been transformed, bankrupted, or acquired. Lehman Brothers went bankrupt. Merrill Lynch and Bear Stearns have been acquired by Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase respectively. The premier remaining prime finance firms, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, are no longer independent. The capital base of the investment banks was risked and lost. The critics and risk managers who warned of the hazards of mixing leverage with speculative investments were terminated, excluded, and vilified prior to the global financial crisis.

The euphoria of the markets, or euphoric episode, has historical precedence. Speculation has been here before and undoubtedly shall return again, whether it is “tulips in Holland, gold in Louisiana, real estate in Florida. . .”1 Once the pendulum of diligence and risk management has swung in favor of a new technology, commodities, or new “riskless” financial instruments that offer easy wealth, then greed will undoubtedly rise in some new, unanticipated form. After all, the financial markets are driven by individuals with a vested interest in their success.

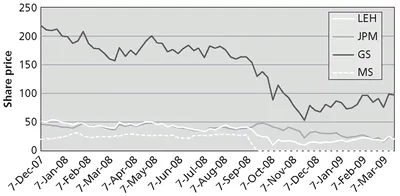

Figure 1.1 Leading Prime Brokers and Lehman

As the economist John Kenneth Galbraith noted, after the Great Depression, “the euphoric episode is protected and sustained by the will of those who are involved, in order to justify the circumstances that are making them rich. And it is equally protected by the will to ignore, exorcise or condemn those who express doubts.”2

However, to blame any one party for the global crisis is overly simplistic, and fails to identify the underlying factors and causes of the current financial crisis. It also fails to yield an understanding of how to reduce the probability of a recurrence or an even worse scenario. The speculation, leverage, and vulnerability of investment banks and financial firms was exposed by the crisis.3 The consequences of highly improbable scenarios were felt by all investment banks, prime brokers, and hedge funds in some form (see Figure 1.1).

Lessons Learned

Today the international economic environment of euphoria has been punctured. Investor and public confidence and trust in the financial system have eroded considerably. That is hopefully a polite way of saying that the bubble has burst, and we are left with the sober task of reviewing the lessons to avoid yet another crisis. A variety of different reports have reviewed the causes, factors, and effects of the financial crisis.

4 In the financial crisis, we learned that:

• Investment banks can and do fail.

• The failure of investment banks, and prime brokers, threatens risks to hedge funds, investors, banks, and ultimately systemic failure.

• Hedge funds provide diversification (and some spectacular results), but do not provide absolute returns in bull and bear markets.

• Hedge fund and broker-dealer managers have been responsible for simplistic frauds on sophisticated clients and advisers.

• Ratings agencies have been unable or unwilling to assess risk accurately.

• Banking and securities regulators were not able to protect the public, investors, or the financial system even with extraordinary regulatory actions.

• Leveraged financing and a massive derivatives market pose a danger to the stability of major banks, financial institutions, insurance companies, pension funds, and even governments.

• Financial innovation and leverage are both important sources of financing but may pose individual, firm, and systemic risks.

• The assessment of risk has been misguided and systemic risks created by interlinkages have not been transparent or understood.

There was a slow chain of antecedents and consequents, causes and effects that impacted the global financial system. The financial reckoning took some time to arrive, but like a tsunami, it was foreseeable to those who looked for the signs, or had an interest in its arrival.5 The global economy has now contracted broadly and deeply. The current crisis in the global economy, financial markets, and international banking system is profound, with no simple solution.

Euphoria and Crisis

The euphoria of private equity, leveraged buyouts, and massive mergers and acquisitions which drove the capital markets into 2007 has disappeared. The bubble in the U.S and U.K housing markets, consumer spending, and easy access to credit fueled the subprime crisis, which brought about catastrophic contractions in liquidity and financing in the debt markets starting in the summer of 2007.

The result in the markets was a massive shift away from mortgage-backed and asset-backed securities and their derivatives. Those individuals and institutions left holding subprime securities had a new name for them: “toxic waste.” The mortgage market downturn in the United States and increasing default rates led to the credit crunch, which in turn led to other consequences, particularly for prime brokers and hedge funds.

In early 2008, Bear Stearns was a leading prime broker. In attempting to catch a falling knife, Bear Stearns’s hedge funds tried to call the bottom of the market. Bear Stearns was hit broadside by the subprime blow-ups of its proprietary hedge funds and other mortgage-backed securities. Their distress caused many financial firms to reduce or eliminate counterparty risks. Prime broker clients removed significant assets from Bear Stearns, fearing that bankruptcy would impact their collateral assets. The impact of the toxic assets on its balance sheet, and a declining prime broker business, made the discount acquisition by JPMorgan Chase, with the support and financing of the U.S. federal government, the only reasonable option other than bankruptcy.

On May 30, 2008, Bear Stearns was acquired by JPMorgan Chase.6 Bear’s toxic assets were subsumed into JPMorgan Chase’s balance sheet with assistance and guarantees from the federal government.7 The Bear Stearns prime broker business continued on under JPMorgan Chase, and hedge funds soon returned their business. The prime finance market continued with business as usual until September 2008.

On September 7, 2008, two of the most significant financial events in modern history occurred. The public did not seem to focus on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac possibly because of their status as semigovernmental organizations. Their distress and conservatorship did not immediately signal the crisis that was to follow. However, for the balance sheet of the U.S. federal government, whether one cuts a check (decreases assets) or assumes the liabilities of an organization (increase liabilities), the financial impact is the same. The sudden conservatorship of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were truly colossal financial and political events. With combined liabilities of approximately 6 trillion dollars, the financial risks of these entities were shifted to the U.S. federal government. The federal government’s action prevented a total collapse of the housing, mortgage and debt markets, but their efforts would not prevent collateral damage to investment banks, financial firms, capital markets, and the OTC derivatives market.

Lehman Brothers

Lehman Brothers was considered by many to be the most vulnerable of the major bulge bracket investment banks. The concern for the future of the bank was public and widely discussed in the media given its public failures to raise capital or find a suitable partner.8 Yet many observers remained optimistic to the end that Lehman Brothers would find a partner. There was no white knight to save the struggling investment bank, however, as there had been for Bear Stearns and would be for Merrill Lynch.

At close of business on September 12, 2008, Lehman Brothers Holding Inc. (LEH) ended trading at $3.65. On that day, Lehman Brothers international operations took extraordinary steps to rehypothecate customer collateral assets and utilized them for financing with a series of stock loan and repo transactions. This is not surprising as the investment bank was struggling for financing. Lehman Brothers did not receive a bailout from the federal government. At the end of the day, the international prime broker, Lehman Brothers (International) Europe, transferred approximately $8 billion from London to the parent holding corporation in New York. The cash swept out of the United Kingdom and other international locations was not returned. Hedge funds assets and other clients had their assets rehypothecated, liquidated, and the cash sent out of the jurisdiction. This was reportedly a normal sweep of cash and securities back to New York in extraordinary times. However, it effectively wiped out the international investment bank and its international clients, some of which were banks, financial firms, and hedge funds.

The Lehman Brothers parent holding corporation had the power to decide which of its hundreds of discrete subsidiaries would receive financing. On Monday morning Lehman Brothers Holding Inc. (LEH) started trading at $0.26, down approximately 93 percent. Some Lehman Brothers entities would receive financing to continue active operations at least for a limited period, while other entities were forced into bankruptcy immediately. The return of the collateral assets remains the source of contentious litigation as the clients and creditors to the international investment bank were effectively left with unsecured claims against a bankrupt firm with minimal assets and extensive liabilities. The battle to return collateral has been further fueled by the rather awkward disclosure that the discount acquisition by Barclays Capital of Lehman Brother’s U.S. brokerage operations resulted in a reported windfall profit of $3.47 billion.9

The long, slow path of Lehman Brothers to bankruptcy pointed out the frailty of unfavored independent broker-dealers and the effects of imposing market discipline over systemic risks. It also exposed the vulnerability of the independent investment banks which were not deemed to pose systemic risk. Not since the junk bond kings, Drexel Burnham Lambert had a major broker-dealer become bankrupt. The Lehman Brothers bankruptcy appeared to be justified in order to restore market discipline leading up to the event and even at the time of the initial bankruptcy filing on September 15, 2008. The potential for systemic failure and contagion was not immediately clear.

Further, the experience of Bear Stearns may have made investors, financial firms, and hedge funds complacent that a government bailout or eleventh hour acquisition was forthcoming. A variety of investors had started negotiations with Lehman Brothers, but for one reason or another, had passed on direct assumption of the business. In light of the massive liabilities to the derivatives and debt markets, potential suitors preferred to scavenge the remaining assets (including many skilled Lehman Brothers’ employees) rather than acquiring a distressed business poisoned with toxic assets and a troubled business model.10

Lehman Brothers’ market capitalization and businesses dropped rapidly prior to its bankruptcy. Ultimately, Lehman Brothers revealed how interconnected the banks, financial institutions, and hedge funds had become. The Lehman Brothers bankruptcy had a catastrophic effect on prime broker clients, stock lending funds, and money market funds which provided liquidity to the markets and were significant holders of ultrasecure short-term U.S. government debt. Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy created broad trading and massive derivative exposures for many of its counterparties. Similarly, credit default swaps on Lehman Brothers created huge gains for some hedge funds and created corresponding liabilities for less fortunate counterparties, such as AIG.

After Lehman Brothers’ collapse, brokers and banks stopped trusting each other. Hedge funds stopped trusting the investment banks and their prime brokers. No hedge fund, prime broker, or investment bank wanted exposure to any other party. Hedge funds reduced their leverage significantly, and the deleveraging cycle of the investment banks and other firms continued. Investment banks reduced lending and the leverage available to clients, and banks ceased lending and borrowing from each other.11 Normal financing transactions ground to a halt after September 16, 2008.

The Run on Money Market Funds

When the damage was revealed the markets panicked. There was a flight to safety. Investors sought only the safest investments; traditionally short-term U.S. government debt was such a safe haven. Money market mutual funds are huge purchasers of U.S. short-term debt, and on September 16, 2008, the Reserve Primary Fund, the oldest money market mutual fund, reported substantial exposures to Lehman Brothers. These exposures to Lehman Brothers reduced the money market mutual fund’s net asset value (NAV) to approximately $0.97. By dipping below a NAV of $1.00, the Reserve Primary Fund had “broken the buck.” Although this is only a small loss, it is an extremely rare occurrence, and it had a massive impact on already nervous and falling markets. If the most liquid and safe investments could lose money, then was any investment safe? Other money market mutual funds soon came under similar pressure from investor redemptions. The run on money market mutual funds and securities lending funds had begun and involved some of the most systemically important firms, including the Bank of New York Mellon.12 U.S. money market funds were redeemed at a record pace. The run on money market mutual funds contracted liquidity and threatened to cause the liquidation of other funds such as the Putnam Investments Prime Money Market Fund.13

The money market funds are important sources of liquidity for the international markets and especially for broker-dealers. The run on money market mutual funds resulted in massive contractions in liquidity as redemptions threatened to swallow up available cash reserves. Updates and assurances from money market mutual funds attempted to allay concerns, including statements of exposures to various notable market counterparties, such as AIG, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, and Washington Mutual.14 Notwithstanding these a...