![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Two Models of Development

“Miss Gaines, send in someone who reminds me of myself as a lad. ”

Our man in the cartoon voices the natural tendency we all have to prefer people who are most like us. This innate human reaction, coupled with an institutionalized set of assumptions about talent, has contributed to the unacceptable waste in human potential that we described in the Introduction. In this chapter we challenge these long-held beliefs about talent and development and replace them with a new set of assumptions that reflect our own experience as well as a growing body of scientific research.

THE HIDDEN POWER OF ASSUMPTIONS

Why bother with assumptions? Why not go directly to action? Management expert Peter Drucker explains why the assumptions that underpin organizational policies and practices related to the development of employees really do matter. “Assumptions decide what in a given discipline is being paid attention to and what is neglected or ignored.” If the assumptions match reality, they are useful guides to effective behavior. But when they do not reflect what is true, they can lead us to wrong decisions. Therefore, if we want to make the best business decisions about people’s capabilities, we have to look behind outward behavior to examine the assumptions that drive it, and then discard those assumptions that are wrong. Once we have established the correct assumptions, we can build the desired behavioral changes.

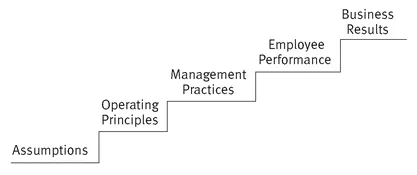

The stairway diagram in Figure 1.1 illustrates the step-by-step linkages we find between initial assumptions and business results.

Figure 1.1: The Links between Assumptions and Business Results

THE “CASTES IN CONCRETE” MODEL OF DEVELOPMENT

Have you heard the old adage “Some have it and some don’t”? This adage is shorthand for various ideas that fall under the assumption of “innate ability”: people are born with certain intelligence levels, talents and abilities that define how much they will achieve in life. Within those confines, people can work hard and achieve more or less with their innate abilities, but the basics are there from birth. We refer to the “innate ability” way of thinking about human capabilities as “Castes in Concrete,” to incorporate both the idea of the social class into which a person is born as well as the idea that what is cast in concrete is fixed and can never change.

We’ve all had experiences with the consequences of this “sort and select” approach, in processes designed to separate out those who are smarter, faster, better, and so on, into various castes. These labels are so pervasive in our society that they even begin at home before we get to school. One sibling is the smartest, another is the cleverest, the most charming, or the best athlete.

Then, when we get to school, we are quickly divided into groups based on ability. Whatever the groups are named, whether robins or sparrows, dogs or cats, we all knew even back then they really represented what we call the “very smarts” (VSs), the “sorta smarts” (Ss), and the “kinda dumbs” (KDs). We can all identify with these individual labels. For some, the groupings are liberating and inspiring; for others, they represent at best a challenge and at worst a “Castes in Concrete” ceiling. Those labels tend to follow us through life, and each of us knows which intelligence label we wear, and therefore which caste we belong to.

Although we undoubtedly know people who were labeled KDs and became successful anyway, we tend to explain those cases as exceptions that prove the rule. Such individuals may be viewed as “overachievers” or discussed in terms like, “It’s amazing what she/he has been able to accomplish.” We are all most likely to skip right over the possibility that the label might have been wrong in the first place.

Almost all human beings have an enormous capacity to learn. Ordinary people demonstrate that capacity by acquiring language at an early age and by “learning” many other highly complex tasks over the course of their lives. This does not mean all people have exactly the same amount of “intelligence,” but it does mean most people have enough intelligence to contribute at very high levels.

Social psychologists have demonstrated the profound impact of “Castes in Concrete” thinking and practices on individual students. Psychologist Carol Dweck, for example, found in her school studies that students who believe “some have it and some don’t” tend to approach life with what might be called a “proving orientation.” This orientation, which starts from the assumption that a person is not perceived as capable and does not perceive him- or herself as capable, has two typical outward expressions. The first is refusal to try at all, perhaps the most common reaction. The second is more complex. Those who do get up the courage to try, spend much of their time proving to their teachers, parents and themselves that they are capable. There is no joy in learning because they have understood from an early age that public labeling and lower status await those designated as “not very smart.” For them, no amount of success is able to change the initial assumption of not being capable. This orientation, then, puts students on a treadmill they can never jump off.

The effect of this “proving orientation” for all is debilitation of effort, and the effort decreases at a greater rate each time a student encounters failure or difficulty. Dweck describes this response to failure or difficulty as the “helpless” response. The children burdened with the “proving orientation” tend to give up more quickly and become apathetic, resisting challenging assignments because they hold a higher probability of failure. Ironically, by avoiding the assignments or projects they fear might cause them to feel less competent, they actually seal their fate. They never have the very experiences that would allow them to become better performers—those activities that would stretch them and make them more competent. If you don’t engage in stretch activities, you will indeed never grow.

Because the “Castes in Concrete” model is so prevalent in society and in educational systems, it’s hardly surprising that the same model finds its way into business and professional organizations. The “Castes in Concrete” assumption that “some have it and some don’t” means the potential of many, if not most, employees is ignored. Here are what we find to be typical indications of organizations built on an exclusionary “Castes in Concrete” model of development.

Recruitment and Selection

Many organizations recruit only from certain schools and offer employment only to people above a target class rank. Others administer intelligence tests to applicants, with threshold scores determining selection. The goal of such practices is often explicitly stated—to employ only people of “proven ability.” The assumptions behind these practices lead us at Novations to ask more questions. What exactly does “proven ability” mean in the work context, especially for those recent graduates interviewing for entry-level positions, with little or no work experience?

What do grades really prove? We have found grades to be a good measure of applied learning, but they may or may not be a good measure of capacity to learn. For example, grades can be a measure of teacher effectiveness or an indicator of where additional effort is needed by both teacher and student. And a student’s ability to achieve high grades can correlate to life circumstances, not just the capacity to learn. Some students, including those who are judged to be the VSs, achieve high grades because they have adequate financial support and can focus on school assignments. Others may need to earn money in order to attend at all, and they must allocate their time to both paid work and completing graduation requirements.

Do the best grades in school prove ability to perform well at work? While many excellent students from top schools go on to perform well at work, we have also heard about many students who did not do as well in school but became star performers at work. Jack Welch was often heard to look for “somebody hungry,” who was driven to succeed. We know of law firms or Wall Street investment banks with an informal requirement that recruits all represent a certain class rank at certain schools, even though a number of the firms’ top money-earning partners do not fit that description.

The ability to balance conflicting priorities may also be more relevant to success in life, including at work, than grade point average alone. Think about the capacity to rebound from failure with an undaunted belief that “I can master this.” Think about the capacity to exercise good judgment in taking moderate risks, discerning and using constructive feedback to improve performance.

Should “proven ability” be limited to having already performed well at the same kind of work? What about someone who has demonstrated the ability to come into a new situation and excel, for example, in combat, by moving to a different high school in a new location or bouncing back from the death of a close friend or relative? Or by being thrust into a leadership position without any warning or preparation and rising to the occasion? While the “proven” worker may be a safe bet, the best companies will want to identify workers who have demonstrated the desire to learn and grow and the willingness to expend maximum effort in any context, because they are most likely to be the source of the greatest productivity and the best new ideas.

Many companies use a technique called “behavioral interviewing” to gain insight into a candidate’s capacity to learn and expend maximum effective effort. Companies first determine what behavioral competencies are critical to success in their organizations and then design questions for applicants that allow them to describe occasions in their lives where they demonstrated those competencies. Behavioral interviewing will be discussed further in Chapter 5.

Performance Management

“Castes in Concrete” thinkers are often comfortable with the “bell curve” to describe the distribution of human intelligence and other job-related abilities in a given population. The bell curve essentially posits that in any random group of people, their individual abilities would fall into three primary categories: 10 per cent in the lowest ranking, 10 per cent in the highest ranking, the 80 per cent in the middle plotted as a giant bell-shaped curve. Since “Castes in Concrete” thinkers tend to view performance as strongly correlated with innate ability, many companies easily adapt the theory to their annual performance evaluations: they demand that the aggregation of evaluations represent a bell curve. A predetermined, fixed percentage of the population must receive the highest and lowest ratings. Such “forced distribution” or “forced ranking” systems have become an acceptable, even favored, performance evaluation tool. Such practices necessarily assume, we believe wrongly, that only a small, predetermined fraction of employees can become top performers, and that a similar predetermined fraction of employees must be found unacceptable.

Potentials Ratings

If ability is “Castes in Concrete,” when someone demonstrates capabilities (or reveals limitations), it becomes possible to predict their future performance and their likelihood of being successful at an organization. Many organizations actually codify this belief, assigning employees numerical “potentials ratings,” for example, 1 for high potential, 2 for medium or modest potential, and 3 for low. These ratings, when used, are usually assigned early in anyone’s tenure, in theory to give managers and HR guidance in placement and assignments. Consider how one new manager responded after realizing the debilitating effects of the potentials ratings:

When I took over my new job the previous manager gave me a piece of paper with the names of all the ‘reliable’ people on one side and the ‘slackers’ on the other. Before I even met the team, he was dividing them up for me, and I didn’t even question it. I handed out assignments accordingly and never even gave the ‘slackers’ a chance. Now when I go back, I’m going to do everything I can to destroy that list.

These labels once applied are difficult if not impossible to overcome or change, even if an employee’s performance demonstrates otherwise. Excellent performances in the case of 3s—or, conversely, poor performances in the case of 1s—are explained as aberrations. Not surprisingly, potentials ratings in most instances are “Castes in Concrete.”

Accelerated Development Programs and Rotational Assignments

Professional employees with high potentials ratings are often placed on a “fast track,” a series of relatively short and often rotating assignments in key segments of the organization. These assignments are designed to expose high potentials to the most important business departments as well as to the key company leaders in order to position them as future leaders. Typically, these strategic assignments rotate them through a series of managerial roles and high-level individual contributor roles in planning, finance, operations, manufacturing, marketing and sales in order to build a cross-functional breadth of knowledge, contacts and skills. Those not put on the “fast track” are generally understood to be out of the running for senior positions.

Employees’ career trajectories can largely be plotted based on these early judgments of ability and potential, and they are carefully controlled thereafter. Only those chosen for the fast track are given the exposure and experiences that are the necessary foundation for senior leadership positions.

Education and Training

Training also follows these same “Castes in Concrete” lines. Sort-and-select organizations invest heavily in training and development for those who are regarded as the high potentials—those equipped to benefit from the stretch opportunities. For the many others, some technical training may be provided, but seldom the developmental experiences that prepare individuals for greater responsibilities and more prestigious and visible assignments. The most valuable training opportunities are reserved for the select few.

IT WORKS FOR SOME

For those few people who have been selected as high potentials, the workplace implications of the “Castes in Concrete” model of development are by and large positive. From their initial contact with an organization—selection, hiring and on-boarding—whether applying for particular positions or recruited as interns, the labels indicate the treatment they are going to receive. They will receive most of their organization’s development opportunities and support.

High potentials will receive the best job assignments—those that have high visibility and are linked to the company’s key business objectives—the most encouragement and coaching support from their managers, the highest performance ratings, skills training on-site, invitations to seminars off-site, formal and informal leadership training, and formal and informal mentoring about how to be effective.

And many, if not most, high potentials rise to the occasion by excelling their stretch assignments. Why wouldn’t they? They are encouraged, coached, mentored and groomed at every turn. We do...