![]()

CHAPTER 1

Laying the Foundation

This book doesn’t profess to have all the answers, but it will provide solutions for, and alternatives to, many valuation issues faced by early stage, venture-backed companies. Furthermore, this book is not a treatise on proper accounting treatment; other books are available that cover that topic, and it should be said that there is little consensus among accounting firms as to how a particular issue should be treated. However, this book does provide an experiential and practical guide to valuing early stage, venture-backed companies. It incorporates what I’ve learned during more than 15 years of focused start-up work along with the collective wisdom of the many practitioners whom I’ve had the joy and honor to work with over the years.

A UNIQUE LANDSCAPE

To really understand the context in which early stage companies are valued, a thorough background of the different economic and socioeconomic environments in which such companies exist is needed. In addition, a working understanding of the venture capital industry is helpful, given that venture capital is the engine that powers these companies to success (success is the goal, even though it’s not always achieved). The following paragraphs and sections lay the basic groundwork for the unique aspects of valuing early stage companies.

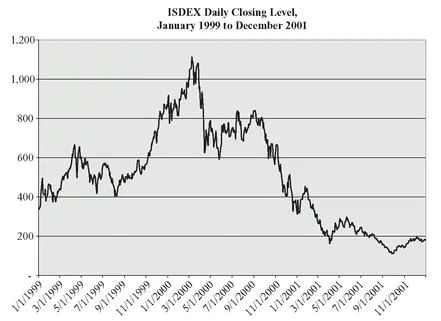

Readers who were performing valuations during the dot-com boom of the late 1990s are familiar with the crazy valuations that were prevalent at the time for early stage companies. Early stage companies, those with little or no revenue or income, were commanding huge valuations, sometimes eclipsing the market values of many well-established “old economy” companies. I look back fondly at that time, recalling how any valuation, no matter how ridiculous, seemed to be accepted—and even revered—by the investing public. Valuation professionals could make no mistake, and “experts” such as Henry Blodgett and Mary Meeker achieved iconic status. But reality finally set in, and the bubble burst with a bang during March and April 2000, as shown in the Internet Stock Index (ISDEX) chart in Exhibit 1.1.

EXHIBIT 1.1 Internet Stock Index, January 1999 to December 2001

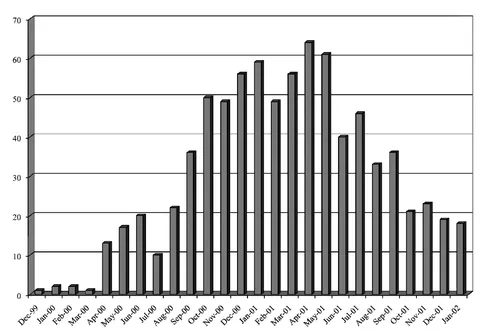

A telling story is that the ISDEX is no longer published as of this writing. Even more telling, however, is that during the two-plus years from December 1999 through February 2002, more than 800 Internet-related companies went out of business, according to Webmergers. The carnage is shown in Exhibit 1.2, which displays an expected inverse of the ISDEX chart and also supports the adage that what goes up must come down.

Ironically, as all of these start-ups began to start down, a new start-up entered the scene in April 2000, Fucked Company, which chronicled the plight of failing Internet companies with humor and irreverence. Styled after Fast Company, a magazine for start-up technology companies that is still in circulation, Fucked Company followed the same path of the very companies it ridiculed, ultimately being sold to TechCrunch in April 2007, seven years after its illustrious start.

EXHIBIT 1.2 Internet Shutdowns and Bankruptcies by Month, December 1999- February 2002

Source: Data from Webmergers, Inc.

At this point, readers may be asking, what does all of this have to do with valuing early stage companies? The fact is that there are no hard-and-fast rules in valuing early stage companies. Although it can be said that valuing closely held companies is more art than science, that statement is even more applicable to early stage companies. A fledgling start-up has too many unknowns, ranging from an inexperienced management team to an iffy customer base to an uncertain market for initial public offerings. When a prominent venture capital expert was asked what figures into his valuations, he answered, “Three guys, a garage, a product, or a beta site.”

We’ve often heard that hindsight is 20/20. Looking back at the dotcom bubble, I wonder how in the world things got so crazy! I believe the answer lies at the core of valuation theory, and specifically in one aspect of that theory—uncertainty. Fundamentally, valuation professionals need only three basic items to value any asset (and I’m not referring to “three guys, a garage, and a product”): (1) an income stream, (2) a discount rate, and (3) a growth rate. A seasoned valuation professional can consider those three things and then value the asset. However, when one or more of those items is unknown or uncertain, the underlying valuation becomes murky. For early stage companies, at least two of the three necessary inputs are subject to substantial uncertainty.

First, the income stream is sometimes little more than an “Excel exercise” based on a spreadsheet model that is typically built on numerous, untested assumptions. Second, the growth of the income stream is a pure SWAG (i.e., scientific wild-ass guess). The importance of the discount rate under these circumstances diminishes—without a relevant and reliable income stream or growth rate, what is there to discount?

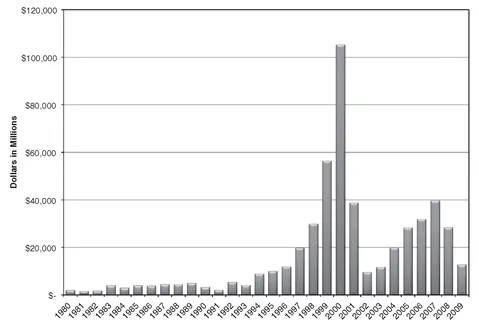

So what was driving such high valuations during the late 1990s? Clearly the Internet played a big role, but that is only on the supply side. On the demand side, capital was flowing like beer at a frat party. This is shown in Exhibit 1.3, which demonstrates the amount of capital committed to venture funds at various times from 1980 through the second quarter of 2009 (annualized). Notice what happened in 1999 and 2000 and even during the residual period in 2001. The stock market frenzy during that time was a capital and business siren beckoning both investor and entrepreneur to drink the Kool-Aid of high valuations. Initial public offerings (IPOs) hit feverish highs, mirroring the amounts of capital companies were able to raise. After a sobering up in 2002, the trend resumed as venture capital commitments began a slow and cautious return through 2007, when the current economic crisis put the brakes on committed capital. The second quarter of 2009 showed the lowest number of funds raising capital since 1996 and the lowest raising of capital since 2003.

EXHIBIT 1.3 Venture Capital Commitments by Year

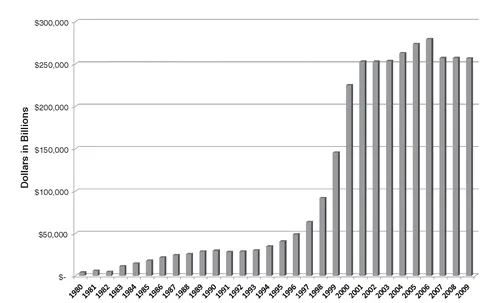

EXHIBIT 1.4 Venture Capital under Management

However, even though capital commitments have slowed, the amount of venture capital sitting on the sidelines waiting for an opportunity to play is staggering, as shown in Exhibit 1.4. More than $250 billion (with a “b”) of capital has been looking for a home since 2001. Interestingly, given the amount of capital raised per year shown in the foregoing chart, it appears that during the past nine years what has been raised has essentially been invested. The lesson to be learned here is that there is plenty of money available to invest but a perceived lack of investment opportunities. What does this say about current valuations?

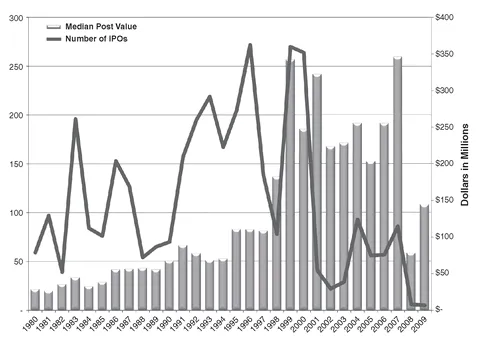

The ultimate goal of any venture capital (VC) fund is to create value for its investors. One thing VC funds focus on to accomplish this goal is liquidity for their investments, which take the form of either mergers/acquisitions or IPOs. As shown in Exhibit 1.5, both the number of IPOs and the amount of capital raised by these IPO companies peaked between the last quarter of 1999 and the first quarter of 2000. Many paper millions were made by thousands of new investors, and some were even lucky enough to sell off before the big crash and convert at least some of their paper profits into real dollars.

The majority, however, were not as fortunate. VC investing plummeted, and IPOs went on a two-year chill. But as with most things in business, the cycle returned; new investment increased, and IPOs began to emerge from the dot-com debacle through 2007. What goes around comes around, though, and a new nadir was reached in 2008, when only five IPOs went out. During the second quarter of 2009, as many new venture-backed IPOs went out as in all of 2008, but currently, it is not clear whether the IPO window will be open again, as it was in 1999 and 2000. I’d say that will be based on the converse of what goes up must come down (i.e., what comes down must go up).

EXHIBIT 1.5 Venture-Backed IPOs

Granted, tremendous business potential was created by the Internet, but no one really knew just how much potential there was. This uncertainty was the primary driver behind the run-up in valuations; investors were afraid that they would miss out if they didn’t invest. Going back to our three valuation ingredients, cash flows were projected to increase at a phenomenal pace (remember “get big fast”?), while discount rates continued to be drawn from the general marketplace for the most part. Since most of these companies didn’t have positive earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA, a common measure of available cash flow), let alone earnings, revenue multiples replaced price-to-earnings (P/E) multiples. The moderation in multiples that one would expect from moving up in the income chain (net income to revenue), however, did not occur. Instead, new terms were invented to “fit” these absurd valuations.

A walk down memory lane brings to mind such valuation metrics as:

• Price to employees

• Price to page views

• Price to click-throughs

• Price to downloads

• Price to personal digital assistants

• Price to property, plant, and equipment (PPE)

• Price to doors passed

• Price to next year’s revenue

You will notice a prevalent lack of financial metrics for obvious reasons. But Internet companies weren’t the only ones looking for valuation validation in the marketplace. Infrastructure players, such as competitive local exchange carriers and cable companies, were being valued based on price to property, plant, and equipment or price to subscribers. Although nonfinancial metrics weren’t new in the late 1990s, they were the only metrics on many occasions.

Performing a valuation engagement for an early stage company requires an approach that is different from a valuation engagement for a typical revenue and income-generating entity. The absence of financial metrics from which to derive value, coupled with intense uncertainty, mandates a different analytical skill set. Such assignments force the valuation professional to delve deeper into the qualitative aspects of the company, its management team, and its market prospects more than is typical in a “traditional” valuation engagement. These roles are discussed ...