![]()

PART I

The Theory

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

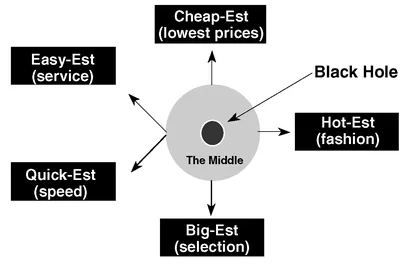

EST: A COMPASS TO AVOID RETAIL’S BLACK HOLE

Beware the Black Hole!

The Black Hole is the place where retail companies that are no longer relevant to customers go to die. As you may recall from high school physics, a black hole is a region in space where the gravitational pull is so strong that not even light can escape. That is also an apt description for retailers that have not established themselves as the best store for customers looking to fulfill a specific need: Once they are in the Retail Black Hole, it’s next to impossible to get out.

In recent years, the number of retailers entering the Black Hole increased as store productivity slowed and competition increased. Not only the small, regional chains were failing. Big-name retailers with hundreds of stores—some nationwide—were going out of business.

Chapter 11 bankruptcy has become practically a household phrase among U.S. consumers, with Kmart filing the largest such case in business history. Unfortunately, so-called Chapter 22 is becoming nearly as common—retailers who restructured their businesses once, only to meet the same bankruptcy fate a few years later down the line.

Frankly, it made our Black Hole presentations better, and we spend more than our fair share of time working with the press to explain what these failures mean to retailing and to consumers. It also became clear to us that these stores were failing because they were not properly responding to the way customers were changing: They had not become best at anything (or had ceased to fill that role) for customers.

Now, because of the Internet, extraordinary access to capital, and nearly instantaneous worldwide communications, retail change is happening faster than ever. Winning chains such as Wal-Mart are continuing to grab market share at an unprecedented rate, while foreign retailers with strong track records, such as Ikea, Zara, and H&M, are becoming a larger part of America’s retail landscape. Entire retail categories—such as variety stores, regional discount stores, regional electronics chains, and catalog showrooms—have all but disappeared. Once-successful retailers are becoming obsolete at a fast pace.

No retailer is immune. Kmart, the nation’s third-largest discount store chain, was forced to file Chapter 11 bankruptcy in January 2002. Less than a decade ago, Kmart was the nation’s second-largest retailer. Other large retail chains that may seem a long way from the brink are also in peril. That’s because stores like Kmart are adrift in a place that we call the Sea of Mediocrity. These stores aren’t best at anything, and they don’t have a distinct or sharply defined customer proposition.

It’s not easy staying on top, either. Over the years, the examples we use to illustrate winning retailers have gone through constant change. Role model retailers like Circuit City and Toys “R” Us have fallen on hard times, failing to react to their own individual inflection points. Even a gold standard retailer like Home Depot is looking into the rearview mirror, as nimbler competitors like Lowe’s do a better job of responding to consumer needs. The immediacy of the retail business and the customer’s response to a retailer’s offer create a constant scorecard with which to measure success. Comparable store sales figures (sales of identical stores currently versus a year ago) provide a running commentary on the industry. We know, almost in real time (Amazon.com showcases a gift meter on its web site), how a company is performing.

The ebb and flow of successful companies is hardly unique to the world of retail. The same phenomena take place every day in any business that serves the consumer. How, though, can one explain this logically, so companies can stay ahead of the curve instead of simply reacting to it? In too many cases, by the time a company is nearing Chapter 11 (or the Black Hole), it is way too late to effect meaningful change with the consumer or on Wall Street. The key, of course, is to determine trouble before it occurs and act accordingly.

EST DEFINED

The breakthrough for McMillan|Doolittle was our drive to articulate retail success in a straightforward way and make sense of the seemingly random changes we were witnessing on a daily basis in the retail world. Our goal was to simplify rather than complicate. We worked hard to be plainspoken and to come up with a better way of explaining things. Ultimately, that led to the development in the early 1990s of what we call the Est theory for retail success.

The Est theory derives from the word best, and it essentially says that a retailer must be best at one proposition that’s important to a specific group of customers. Retailers must strive for a specific positioning to a specific set of customers rather than attempting to be great at everything to everybody. To accomplish this might mean targeting a specific customer at the exclusion of others, giving up on merchandise categories that today might still be yielding profitable sales, or forgoing short-term growth and profits with an eye toward long-term success. These ideas were heretical for most retailers at the time and are concepts that most struggle with even today.

Est originated through an analytical exercise in which we systematically studied winning retailers (as defined by sales growth and profitability) to determine what made them tick. As we tried to discern the key attributes that made them successful, a rather startling pattern emerged. In those companies that had a singular defining characteristic from a consumer perspective, we saw well-above-average financial results, even among companies pursuing seemingly disparate aims. Companies for which we could not isolate any one defining reason for being almost inevitably wound up somewhere in the middle of the pack. It became clear to us that being the best with consumers had a clear impact on the bottom line.

Do you really have to be best to succeed? We are often asked that by our retail and service company clients who proudly show how good they are in many areas. As Jim Collins proclaimed in his book Good to Great, “Good is the enemy of great.” We agree, and we take it one step further. “Pretty good” are words retailers should dread, because if you are not an Est retailer and you’re still in business, that’s probably how customers describe you: “Pretty good.” That means customers have other stores they’d rather shop. Sooner or later (most likely sooner) they will find those stores or those stores will find them, and they won’t come back to you. Today’s time-starved shoppers don’t frequent mediocre stores.

Clearly, customers have less time to shop. They are also more knowledgeable about the products they want to buy and the stores that sell them. They have more choices of where to shop than ever before.

The customers who still frequent mediocre stores probably do so because of a historic attachment—it’s where they or their parents always shopped. Or they were attracted to the mediocre store because of a sales promotion. Or they simply didn’t have the time or energy to drive to a preferred store. Finally, being handy to where they live or work certainly helps. We can hardly dispute the old retail adage—location, location, location. Yet consumer research indicates that it is the proverbial kiss of death if location is the primary reason customers shop at your stores—someone else can always get closer.

Whatever the case, these types of customer relationships do not have a bright future, which is why pretty good isn’t good enough anymore.

Many of the stores now enshrined in our Black Hole memorial were pretty good stores. (See Figure 1.1.) Montgomery Ward, for instance, ranked third or fourth by consumers as places they’d likely shop for various items. While Wards wasn’t anything-Est, at least it was a close also-ran in some categories. That doesn’t sound too bad. Not many people hated Wards—but even worse, they were simply indifferent. How’s Wards on price? “Pretty good.” How’s Wards on service? “Pretty good.” How’s Wards on fashion? “Pretty good.”

FIGURE 1.1 Black Hole Memorial

How’s Wards on assortment? “Pretty good.” Those kinds of results from customer surveys may have seemed pretty reassuring to Wards’ executives. Actually, being pretty good at lots of things was the foundation of the modern era of mass retailing for general-merchandise stores. It was a pretty good formula into the 1980s. It’s not anymore.

Pretty good stores cannot satisfy increasingly demanding customers. Pretty good stores also cannot compete with today’s sharpest retail chains. Stores like Wal-Mart, Target, Costco, and Kohl’s have raised customer expectations. Falling short of expectations means not satisfying customers, and that’s the most direct path to the Black Hole.

EST IS NOT A MARKETING TOOL

Est is not simply a “marketing thing,” a way to position a company in advertising and external communications. The buzzword today is branding, and while we believe in the concept, too many companies confuse the articulation of a marketing and/or design message with the essence of the company. Est Retailers devote themselves with laserlike focus to their core customer proposition, what we call their Est position. They commit employees from the top to the bottom of their organization to that position. They communicate that positioning to their customers and execute it relentlessly at the store level. Est retailers also base strategic and day-to-day operational decisions on their positioning. An Est positioning is not simply the marketing message du jour—it is a way of life for successful retailers.

Wal-Mart is the quintessential example. Everything Wal-Mart does is focused on enhancing its position as the low-price leader. With its “Always Low Prices” tagline and “Everyday Low Price” positioning, Wal-Mart wins with customers on price. Yet this is not merely an advertising proposition—the drive for lower prices for the consumer defines every action that the company takes. It is at the heart of Wal-Mart’s mission, its very reason for being. Sam Walton founded what is now the world’s largest company (period, not just in retail) on the simple belief that customers would like to pay less for the products they purchase and that ordinary folks should have the opportunity to buy products that make their lives better. Every single action the company takes is measured against these fundamental principles.

We call that particular Est Cheap-Est (and it has served companies like Wal-Mart very well). The other Est positions that win customers are Big-Est, having the largest assortment of product in a specific merchandise category; Hot-Est, having the right products just as customers begin to buy them in volume; Easy-Est, having the proper combination of products and services that makes shopping easy; and Quick-Est, organizing the store to make the shopping trip as quick and efficient as possible. (See Figure 1.2.)

FIGURE 1.2 Est Model

THE INTRODUCTION OF EST

Norm McMillan, one of the company’s founding partners, first presented the Est theory in the early 1990s at an international food industry trade show in France. It played well in Paris (and subsequently Peoria), and we’ve been using and fine-tuning the model ever since. The theory has resonated with our clients (and to audiences throughout the world) for more than a decade because its message is easy to grasp and is actionable.

By further studying these companies, we also recognized they had done much more than carve out a niche. They weren’t simply the best among their rivals by default. These retailers had devoted their organizations from top to bottom to becoming the best in one particular area. It was the driving force of their businesses. Once we identified what the winning retailers strove to be best at for customers, the Est theory was born.

We liked the model we had hatched. It made sense to us. But we were waiting for someone to fire a silver bullet, to raise a question or example that Est couldn’t easily answer or explain. We’re still waiting.

DOES EST CHANGE? ABSOLUTELY

We created Quick-Est in the mid-1990s to recognize the growing importance of saving customers time and to recognize that retailers can win by focusing on providing customers with time savings as a key benefit. While this may have always been true, consumer trends (working women, less free time) finally made time a critical currency that we could effectively model. Who’s to say that another driving element won’t emerge as the consumer continues to evolve? However, we are cautious in screening between a fad and a key consumer trend.

In the mid-1990s, we also heard from people who thought we shoul...