- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sleep Medicine Essentials

About this book

Based on the highly acclaimed Sleep: A Comprehensive Handbook, this is a concise, convenient, practical, and affordable handbook on sleep medicine. It consists of forty topic-focused chapters written by a panel of international experts covering a range of topics including insomnia, sleep apnea, narcolepsy, parasomnias, circadian sleep disorders, sleep in the elderly, sleep in children, sleep among women, and sleep in the medical, psychiatric, and neurological disorders. It serves as an effective Sleep Medicine board examination review, and every chapter includes sample boards -style questions for test preparation and practice.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

NORMAL HUMAN SLEEP

INTRODUCTION

Normal human sleep is comprised of two distinct states, known as nonrapid eye movement (NREM) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. NREM sleep is subdivided into four stages, namely stages 1, 2, 3, and 4, which have been recently reclassified to stages Nl, N2, and N3. REM sleep may also be further subdivided into two stages, phasic and tonic.

ADULT SLEEP ARCHITECTURE

NREM Sleep

Nonrapid eye movement sleep accounts for 75–80% of total sleep time:

- Stage 1 (Nl) sleep comprises 3–8% of total sleep time. Nl sleep occurs most frequently in the transition from wakefulness to the other sleep stages or following arousals from sleep. In Nl sleep, alpha activity (8–13 Hz), which is characteristic of wakefulness, diminishes and a low-voltage, mixed-frequency pattern emerges. The highest amplitude electroencepha-lography (EEG) activity is generally in the theta range (4—8 Hz). Electromyography (EMG) activity decreases and electro-oculography (EOG) demonstrates slow rolling eye movements. Vertex sharp waves (50–200 ms) are noted toward the end of Nl sleep

- Stage 2 (N2) sleep begins after approximately 10–12 min of Nl sleep and comprises 45–55% of total sleep time. The characteristic EEG findings of N2 sleep include sleep spindles and K complexes. A sleep spindle is described as a 12 to 14-Hz waveform lasting at least 0.5 s and having a "spindle"-shaped appearance. A K complex is a waveform with two components, a negative wave followed by a positive wave, both lasting more than 0.5 s. Delta waves (0.5–4 Hz) in the EEG may first appear in N2 sleep but are present in small amounts. The EMG activity is diminished compared to wakefulness.

- Stage 3 and 4 (N3) sleep occupy 15–20% of total sleep time and constitute slow-wave sleep. N3 sleep is characterized by greater than 20% of high-amplitude, slow-wave activity. EOG does not register eye movements in N2 or N3 sleep. Muscle tone is decreased compared to wakefulness or Nl sleep.

REM Sleep

Rapid eye movement sleep accounts for 20–25% of total sleep time. The first REM sleep episode occurs 60–90 min after the onset of NREM sleep. EEG tracings during REM sleep are characterized by a low-voltage, mixed-frequency activity with slow alpha (defined as 1–2 Hz slower than wake alpha) and theta waves:

- Based on EEG, EMG, and EOG characteristics, REM sleep can be divided into two stages, tonic and phasic. Characteristics of the tonic stage include a desynchronized EEG, atonia of skeletal muscle groups, and suppression of monosynaptic and poly-synaptic reflexes. Phasic REM sleep is characterized by rapid eye movements in all directions as well as by transient swings in blood pressure, heart rate changes, irregular respiration, tongue movements, and myoclonic twitching of chin and limb muscles. Sawtooth waves, which have a frequency in the theta range and have the appearance of the teeth on the cutting edge of a saw blade, often occur in conjunction with rapid eye movements.

NREM-REM Cycle

The NREM-REM sleep cycle occurs about every 90 min, and approximately four to six cycles occur per major sleep episode. The ratio of NREM sleep to REM sleep in each cycle varies during the course of the night:

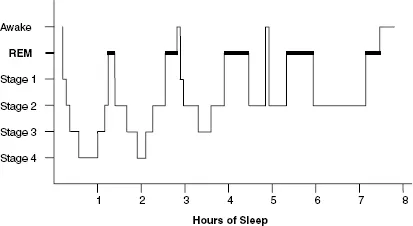

Figure 1.1 Young adult hypnogram.

- The early cycles are dominated by slow-wave sleep and REM sleep dominates the later cycles. The first episode of REM sleep may last only a few minutes and subsequent REM episodes progressively lengthen in duration during the course of the major sleep period.

- N3 sleep is prominent in the first third of the night and REM sleep is prominent in the last third of the night. The temporal arrangement of sleep type is described graphically by a hypnogram (Fig. 1.1).

SLEEP IN NEWBORNS AND INFANTS

Adult sleep stages and features are not evident until 6 months of age. Newborn sleep states are characterized as quiet, active, or indeterminate:

- Quiet sleep is analogous to NREM sleep. EEG demonstrates a discontinuous pattern with intermittent bursts of electrical activity alternating with quiescent periods. Heart rate and respirations are regular, body movements are few, and EMG activity is sustained.

- Active sleep is analogous to REM sleep. EEG demonstrates a low-voltage, irregular pattern. Rapid eye movements, body movements, grimaces, and twitches are frequent. Muscle tone, heart rate, and respirations are variable.

- Indeterminate sleep is disorganized and cannot be classified as either active or quiet sleep.

- Vertex sharp waves develop between 0 and 6 months of age. Sleep spindles develop between 4 and 8 weeks of age. Kcomplexes develop between 4 and 6 months of age.

- The newborn sleep cycle is about 60 min. The cycle starts with active sleep. At term, over 50% of a newborn's sleep is active. Sleep-onset REM periods are normal until 10—12 weeks of age. During the first 6 months of life, there is a decrease in the amount of active sleep and a simultaneous rise in the amount of quiet sleep. The sleep cycle gradually increases to the adult average of 90 min by adolescence.

CHANGES IN SLEEP WITH AGING

Sleep patterns change during life. Newborns may spend more than 16 h of the day asleep but intermittently sleep and awaken throughout the 24-h period. At the age of 3 months, infants may sleep throughout the course of the night and may take two or more daytime naps. As the child first enters school, sleep is consolidated into a major nocturnal period with a single daytime nap. As the child ages into adulthood, the major nocturnal sleep is not accompanied by a daytime nap. Age-associated deterioration of the sleep pattern results in fragmented sleep in the elderly in whom more time is spent in bed but less time asleep.

Slow-wave sleep and REM sleep patterns also change during life. Slow-wave sleep declines after adolescence and continues to decline as a function of aging. REM sleep decreases from more than 50% at birth to 20–25% during adolescence and middle age.

SLEEP NEUROPHYSIOLOGY

NREM Sleep

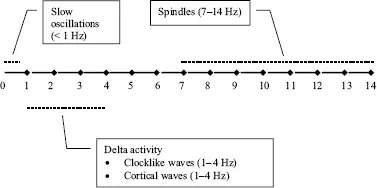

The transition from wakefulness to NREM sleep is associated with altered neurotransmission at the level of the thalamus whereby incoming messages are inhibited and the cerebral cortex is deprived of signals from the outside world. NREM sleep is characterized by three major oscillations (Fig. 1.2).

- Spindles (7–14 Hz) are generated within thalamic reticular neurons that impose rhythmic inhibitory sequences onto thalamocortical neurons. However, the widespread synchronization of this rhythm is governed by corticothalamic projections.

- There are two types of delta activity. The first type are clocklike waves (1–4 Hz) generated in thalamocortical neurons and the second type are cortical waves (1–4 Hz) that persist despite extensive thalamectomy. However, the hallmark of NREM sleep is the slow oscillation (<1 Hz), which is generated intracortically and has the ability to group the thalamically generated spindles as well as thalamically and cortically generated delta oscillations, leading to a coalescence of the different rhythms.

Figure 1.2 NREM sleep oscillations.

REM Sleep

Transection studies demonstrate that the pontomesence-phalic region is critical for REM sleep generation. When the mesopontine region is connected to rostral structures, REM sleep phenomena such as a desynchronized EEG and ponto-geniculo-occipital (PGO) spikes are seen in the forebrain. When the mesopontine region is continuous with the medulla and spinal cord, REM sleep phenomena such as skeletal muscle atonia can be seen.

- The pontomesencephalic area contains the so-called cholinergic "REM-on" nuclei, specifically the later-odorsal tegmental (LDT) and pedunculopontine teg-mental (PPT) nuclei. The LDT and PPT nuclei project through the thalamus to the cortex, which produces desynchronization of REM sleep. The LDT and PPT nuclei project caudally via the ventral medulla to alpha motor neurons in the spinal cord where skeletal muscle tone is inhibited during REM sleep by the release of glycine.

- PGO spikes are precursors to the rapid eye movements seen in REM sleep, are formed in the cholinergic mesopontine nuclei, and propagate rostrally through the lateral geniculate and other thalamic nuclei to the occipital cortex.

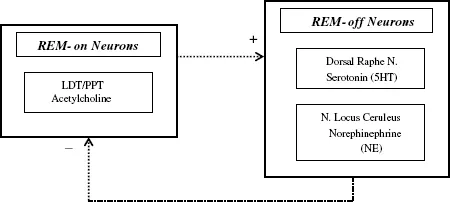

- In addition, as NREM sleep transitions to REM sleep, tonic inhibition of REM-generating cholinergic pontomesencephalic nuclei by brainstem serotoni-nergic and adrenergic nuclei decreases, thereby allowing the development of PGO spikes and muscle atonia. Thus, the cholinergic REM-on nuclei of the PPT and LDT slowly activate the monoaminergic "REM-off" nuclei of the dorsal raphe and locus ceruleus that in turn inhibit REM-on nuclei (Fig. 1.3).

- Hypocretin has an important role in the modulation of wakefulness and REM sleep. Hypocretin neurons are located in the perifornical region of the lateral hypothalamus and widely project to brainstem and forebrain areas, densely innervating monoaminergic and cholinergic cells. Hypocretin neurons promote wakefulness and inhibit REM sleep. Elevated levels of hypocretin during active waking and in REM sleep compared to quiet waking and slow-wave sleep suggest a role for hypocretin in the central programming of motor activity. Hypocretin projections to the nucleus pontis oralis may play a role in the generation of active (REM) sleep and muscle atonia.

Figure 1.3 NREM-REM reciprocal interaction model.

Table 1.1 Autonomie Nervous System Fluctuations During Normal Human Sleep

| Parasympathetic Nervous System | Sympathetic Nervous System | |

| NREM sleep | Increase | Decrease |

| REM sleep | ||

| Tonic | Increases further | Decreases further |

| Phasic | Intermittent increases |

AUTONOMIC NERVOUS SYSTEM

The autonomie nervous system (ANS) regulates the vital functions of internal homeostasis. The ANS is comprised of the sympathetic nervous system and parasympathetic nervous system.

- The essential autonomie feature of NREM sleep is increased parasympathetic activity and decreased sympathetic activity.

- The essential autonomie feature of REM sleep is an additional increase in parasympathetic activity and an additional decrease in sympathetic activity, with intermittent increases in sympathetic activity occurring during phasic REM (Table 1.1) For example, pupilloconstriction is seen during NREM sleep and is maintained during REM sleep with phasic dilatations noted during phasic REM sleep.

MODEL OF SLEEP REGULATION

Several models have been proposed to explain the regulation of sleep and wakefulness. One such model proposes that two processes govern the regulation of the sleep—wake cycle: a sleep-dependent homeostatic process (process S) and a sleep-independent circadian process (process C).

Process S is a homeostatic process that is dependent upon the duration of prior sleep and waking. This process shows an exponential rise during waking and a decline during sleep. In other words, the longer a person stays awake, the sleepier he or she becomes; conversely, the longer a person sleeps, the lower the pressure to remain asleep.

Process C is a circadian process that is independent of duration of prior sleep and waking. This process is under the control of the suprachiasmatic nucleus, which determines the rhythmic propensity to sleep and awaken. Each person has an endogenous drive to fall asleep and awaken at a certain time regardless of the duration of prior sleep or wake.

- The two-process model posits that the timing of sleep and waking is determined by the interaction between process S and process C. Sleep onset is thought to occur when both the homeostatic and circadian drive to sleep intersect.

- Other models have also been proposed, such as the opponent-process model and the three-process model of alertness regulation; however, further work is necessary to determine the biological substrates of the elements of these models and the pathways by which they interact.

KEY POINTS

1. The adult NREM-REM sleep cycle occurs every 90 min with early cycles dominated by slow-wave sleep and the later cycles dominated by REM sleep.

2. Until the age of 6 months, newborn sleep states are characterized as quiet, active, or indeterminate. Quiet sleep is analogous to NREM sleep; whereas, active sleep is analogous to REM sleep.

3. The essential autonomie feature of NREM sleep is increased parasympathetic activity and decreased sympathetic activity. The essential autonomie feature of REM sleep is an additional increase in parasympathetic activity and an additional decrease in sympathetic activity, with intermittent increases in sympathetic activity occurring during phasic REM sleep.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Borbely AA. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum Neurobiol 1982; 1:195–204.

Holmes CJ, et al. Importance of cholinergic, GABAergic, serotonergic and other neurons in the medial medullary reticular formation for sleep-wake states studied by cytotoxic lesions in the cat. Neuroscience 1994; 62:1179–1200.

Rechtschaffen A, Kales A (Eds). A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. BIS/BRI, UCLA, Los Angeles, 1968.

2

NEUROBIOLOGY OF SLEEP

INTRODUCTION

Rational questions on the nature of sleep behavior have a long published history and, with littl...

Table of contents

- COVER PAGE

- TITLE PAGE

- COPYRIGHT PAGE

- PREFACE

- CONTRIBUTORS

- 1: NORMAL HUMAN SLEEP

- 2: NEUROBIOLOGY OF SLEEP

- 3: PHYSIOLOGIC PROCESSES DURING SLEEP

- 4: NEUROPHARMACOLOGY OF SLEEP AND WAKEFULNESS

- 5: INSOMNIA: PREVALENCE AND DAYTIME CONSEQUENCES

- 6: CAUSES OF INSOMNIA

- 7: EVALUATION OF INSOMNIA

- 8: PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY OF INSOMNIA

- 9: NONPHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY OF INSOMNIA

- 10: NARCOLEPSY

- 11: IDIOPATHIC HYPERSOMNIA

- 12: POSTTRAUMATIC AND RECURRENT HYPERSOMNIA

- 13: EVALUATION OF EXCESSIVE SLEEPINESS

- 14: THERAPY FOR EXCESSIVE SLEEPINESS

- 15: ADULT SLEEP-DISORDERED BREATHING

- 16: CENTRAL SLEEP APNEA

- 17: OBESITY HYPOVENTILATION SYNDROME

- 18: CARDIOVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS OF OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA

- 19: NEUROCOGNITIVE AND FUNCTIONAL IMPAIRMENT IN OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA

- 20: POSITIVE AIRWAY PRESSURE THERAPY FOR OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA

- 21: ORAL DEVICES FOR OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA

- 22: CIRCADIAN RHYTHM SLEEP DISORDERS

- 23: JET LAG

- 24: SHIFT WORK SLEEP DISORDER

- 25: THERAPY OF CIRCADIAN SLEEP DISORDERS

- 26: DISORDERS OF AROUSAL AND SLEEP-RELATED MOVEMENT DISORDERS

- 27: REM SLEEP BEHAVIOR DISORDER AND REM SLEEP-RELATED PARASOMNIAS

- 28: RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME AND PERIODIC LIMB MOVEMENT DISORDER

- 29: SLEEP IN INFANTS AND CHILDREN

- 30: OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA IN CHILDREN

- 31: THE SLEEPLESS CHILD

- 32: THE SLEEPY CHILD

- 33: NORMAL SLEEP IN AGING

- 34: ASPECTS OF WOMEN’S SLEEP

- 35: ASTHMA

- 36: CHRONIC OBSTRUCTIVE PULMONARY DISEASE AND SLEEP

- 37: RESTRICTIVE THORACIC AND NEUROMUSCULAR DISORDERS

- 38: CONGESTIVE HEART FAILURE

- 39: SLEEP AND THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

- 40: RENAL DISEASE

- 41: ENDOCRINE AND METABOLIC DISORDERS AND SLEEP

- 42: IMMUNITY AND SLEEP

- 43: DEMENTIA

- 44: NEURODEGENERATIVE DISORDERS

- 45: PARKINSON’S DISEASE

- 46: SEIZURES

- 47: SCHIZOPHRENIA

- 48: MOOD DISORDERS

- 49: ANXIETY DISORDERS

- 50: ALCOHOL, ALCOHOLISM, AND SLEEP

- 51: DRUGS OF ABUSE AND SLEEP

- 52: POLYSOMNOGRAPHY

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sleep Medicine Essentials by Teofilo L. Lee-Chiong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Neurology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.