eBook - ePub

Making Sense of the Dollar

Exposing Dangerous Myths about Trade and Foreign Exchange

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Has the greenback really lost its preeminent place in the world? Not according to currency expert Marc Chandler, who explains why so many are—wrongly—pessimistic about both the dollar and the U.S. economy. Making Sense of the Dollar explores the many factors—trade deficits, the dollar's role in the world, globalization, capitalism, and more—that affect the dollar and the U.S. economy and lead to the inescapable conclusion that both are much stronger than many people suppose. Marc Chandler has been covering the global capital markets for twenty years as a foreign exchange strategist for several Wall Street firms. He is one of the most widely respected and quoted currency experts today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Making Sense of the Dollar by Marc Chandler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Foreign Exchange. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

MYTH 1

The Trade Deficit Reflects U.S. Competitiveness

Which car is more American: a Honda Civic sedan made in Ohio or a Chrysler Town & Country minivan made in Ontario?

A car begins with a design. An engineer imagines what it should look like and how all the pieces should fit together. Someone else mines the iron ore that will become the steel; another person mines the platinum that will go into the catalytic converter; and still another person slaughters the cow for the leather interior. The manufacturer brings all the pieces together for assembly according to the design. The car’s buyer, of course, has to fill it up with gas before going anywhere. Every step is important, but some add more value than others. The slaughterhouse worker, for example, needs few skills beyond strength, and the leather that his work generates isn’t integral to the finished product; it could be replaced by cloth or vinyl. The engineer, on the other hand, is key because without her basic design, there is no car. If she develops a great new body shape or an engine that uses less gasoline, then she can add a lot of value to the finished product. She can directly influence how much the car costs and how well it sells.

Although different processes add different amounts of value, the system of accounting for international trade looks at the movement of goods and services over national borders and has no appreciation for ownership. Setting aside the huge problems that the General Motors Corporation (GM) has experienced in its U.S. operations—brought on by bad choices in product design and labor decisions, etc., but that’s another issue—GM’s basic business strategy perfectly exemplifies how a U.S. multinational company’s structure interacts with the trade deficit and the dollar. When GM makes parts in the United States, sends them to Canada to put into Chevy Impalas, and then ships those Impalas back to the United States for sale, the company has engaged in two international transactions: it exported the parts and imported the car. The parts cost less than the finished car, so GM’s imports exceeded its exports, adding to the U.S. trade deficit; yet all the transactions took place within the virtual walls of the same U.S. corporation. Essentially, GM is moving goods from one side of the corporate factory to the other; it’s just that the forty-ninth parallel weaves in and out across the floor. (Amazingly, the movement of goods and services within the same company accounts for half the U.S. trade deficit.)

We’ve all heard the worries: America has turned its global supremacy over to the Chinese. Our jobs are going to China, and the Chinese are practically buying the U.S. government because they buy all our Treasury bonds. The main piece of evidence cited for this is the U.S. trade deficit. In 2008, the United States recorded an average monthly trade deficit of slightly more than $57 billion. It shows how miserable the United States has become. As Americans consume more than they produce, or invest more than they save, China is quickly moving into ascendancy.

Right?

Wrong. But that’s the way too many people think of foreign trade. Too often the focus is strictly on this number called a deficit. It is simply understood that deficits are bad, and what’s happening behind the numbers is frequently left unexamined. Americans produce ideas, and ideas can generate a spectacular amount of money. Microsoft, for example, doesn’t produce much that anyone can touch or feel, but its software has changed the way that we all live, work, and play. How do we account for that? Software, drug patents, product designs, secret formulas, and desirable brand names generate huge profits from all over the world for American companies. When those companies move goods and services between their own offices, it can contribute to the U.S. trade deficit.

Trade accounting is misunderstood. It was designed for a world that no longer exists, one in which dominant nations exported and weak ones imported. Now, goods, services, and ideas flow across borders, as does investment capital. Companies can parcel out business operations not only around the globe but also within the same corporate entity. The trade deficit is large, but it is not a sign of national weakness, nor is it a twin of a budget deficit as is often portrayed. American workers and American companies are still the envy of the world, even if it’s not apparent looking at the trade deficit.

How Trade Accounting Works

At its simplest level, the trade deficit is the value of goods and services exported minus the value of goods and services imported. However, the accounting for it gets complicated. How do we value goods made and sold overseas under patents and trademarks developed in the United States? What if the basic assembly is done overseas but the finishing work is done here? What if the parts are manufactured in three different countries? What if a U.S. retailer asks a clothing manufacturer to start shipping goods on hangers instead of folded in boxes? How much value do those hangers add?

To keep track of the funds that cross borders, nations rely on a system of accounting called the balance of payments (BOP).

In each nation, a central agency (in the United States, the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis) collects data, adds up the value of all imports that come into the country during a set time period, and then compares the total to the value of all items exported. For the purposes of the argument here, we will leave aside issues relating to the bias of the data collection. There is a vested interest in documenting imports, since the government often collects a duty or tax. There are also security reasons for documenting imports. Exports are a different story. The full value of U.S. exports may not be fully captured in the official data.

The transactions are separated into three accounts. The goods and services trade account only includes imports and exports. The current account includes the goods and services trade account along with worker remittances, tourism, and transfer payments (i.e., foreign aid, charity, gifts to relatives overseas, as well as interest and profits from capital investments, royalties, and licensing fees). The capital and financial account includes investments made by individuals, corporations, and governments.

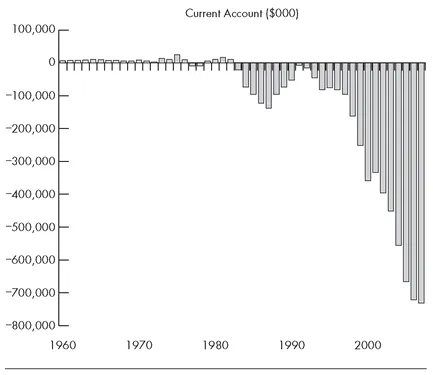

A country that exports more goods and services than it imports will have a trade surplus. A country that imports more than it exports will have a trade deficit—and the United States has had a trade deficit for more than thirty years. Intuitively, we know that surpluses are good and deficits are bad, but international trade is far more complicated than that. A trade surplus doesn’t mean that a nation is getting ahead, and a deficit doesn’t mean that it is falling behind. What matters more are the reasons for a deficit or surplus. Is a country importing because its service-industry workers are prosperous? Or is it importing because its economic base is so primitive that there are no goods to export and imports arrive almost entirely in the form of charity?

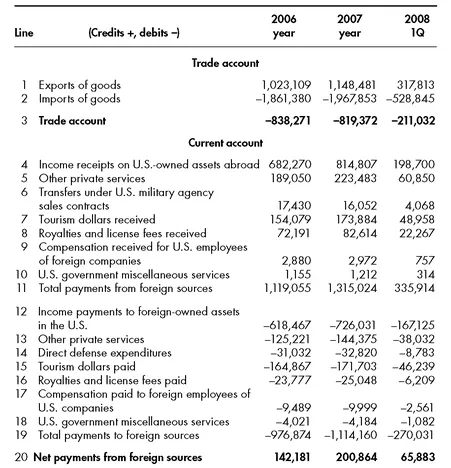

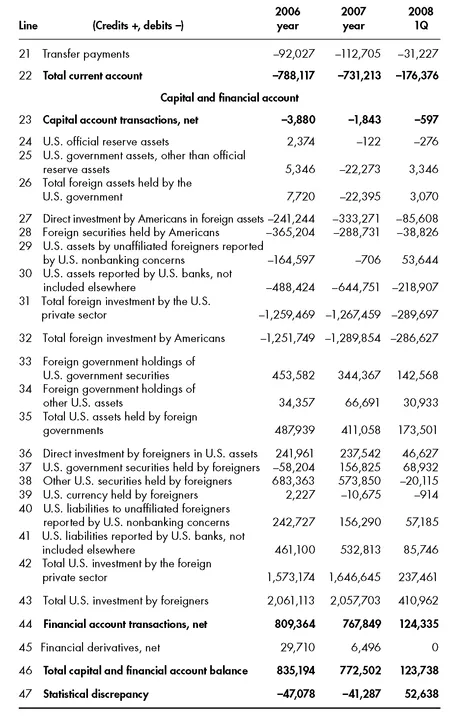

Table 1.1 illustrates the international trade transactions of the United States from 2006 to 2008, showing how Americans do business around the world.1 The trade deficit is calculated in the current account by subtracting imports from exports (line 1 - line 2 = line 3).

TABLE 1.1 U.S. Balance of Payments (2006-2008 Data) in Millions of $

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce.

Although the current account’s traditional components are raw materials and finished goods, services are included, although the total value may be more difficult to track. Goods go through customs; at points of entry, they are tallied and inspected. But services? When a British family flies to Orlando for vacation, it’s as though American companies are exporting vacation services. But just exactly how much money did the family spend on hotel rooms, amusement park tickets, food, transportation, and incidental services? Did anyone tip the hotel maid? Many of these numbers are estimates that may throw off the values in the current account (see Figure 1.1).

The total current account (Table 1.1, line 22) includes money as well as goods. These payments include income from U.S. businesses overseas, e.g., the profits that accrue to McDonald’s from its global restaurant operations (Table 1.1, line 4). The current account includes dividends that American investors receive from their investments in international stocks (Table 1.1, line 4), and it includes compensation earned by American workers employed by foreign companies (Table 1.1, line 17). It shows how the money flows to and from Americans, but it doesn’t always capture the total economic value of what is being transferred. Does importing raw materials and exporting finished goods leave more value in the United States than importing accounting services and exporting software? Than importing profits and exporting brand names? Than importing actresses and exporting movies?

FIGURE 1.1 Americans Have Imported More than They Have Exported Every Year Since 1983

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “U.S. International Transactions: First Quarter 2008,” June 17, 2008.

The capital account (Table 1.1, line 23) includes net transactions in nonfinancial assets, usually real estate or businesses. Capital imports are as controversial as current account imports. They include money that comes into the country when a German or Japanese company acquires a business or builds a factory here, which sometimes generates concerns about the increased role of foreign businesses in this country.

Capital can be exported, and Americans export capital all the time. McDonald’s, Coca-Cola, and Procter & Gamble became household brands worldwide by exporting capital. Companies do it when they buy an international subsidiary or open a sales office overseas.

General Motors, which has been hobbled by its U.S. operations, sold more than one million cars in China in 2007, giving it nearly one-eighth of one of the fastest-growing auto markets in the world and making it the largest foreign automaker in the country.2 None of those cars were made in the United States; most were assembled in China. That GM plant in Shanghai? It represents an export of capital that began in the early part of the twentieth century. And it’s not just GM. Individuals export capital when they buy vacation condominiums in Mexico. In the first quarter of 2008, Americans exported $597 billion in capital.3

The balance of payments is set up as an identity equation: the current account (Table 1.1, line 22) equals the capital account (Table 1.1, line 23) plus the financial account services (Table 1.1, line 44). The financial account has two components: private assets (Table 1.1, lines 31 and 42) and official assets (Table 1.1, lines 26 and 35). Private assets are the financial investments in stocks and bonds made by individuals and businesses. Along with imports and exports of goods, services, and corporate capital, a lot of money flows over national boundaries. When the BOP was invented, it would have been unimaginable that an average American could buy software delivered over the Internet by an Indian company, let alone purchase shares in companies traded on the Hong Kong exchange simply by clicking on a button. But that’s the reality. The Internet, standardized financial contracts, and an awareness of how many great investment opportunities there are around the world have whetted the American appetite for international investing. It’s a simple matter to buy a global mutual fund, a developing market exchange-traded fund, or a stock of a company based somewhere else. These transactions fall into the financial account (Table 1.1, line 44).

By definition, the balance of payments has to balance. It includes so many transactions, however, many of which are estimates, that it never equals exactly zero. That’s why it includes a plug factor, a statistical discrepancy figure (Table 1.1, line 47) that forces the calculation to balance. It’s nothing more than an offset to the imbalance that has been created by the estimates themselves. However, it does not balance over several quarters even though in theory it should. (Some people think this might be a measure of smuggling, drug trades, and terrorist activities that aren’t reported on customs forms or income tax filings.) It is often statistically significant. In the first quarter of 2008, for example, the statistical discrepancy was at $51.6 billion on a $176.4 billion estimated current account deficit.4

And that is the balance of payments.

What Do All Those Numbers Mean?

The BOP figure, which the United States publishes quarterly, was established during an era in which currencies did not float freely and capital mobility was limited. Under the Bretton Woods agreement of 1944, the exchange rate for the dollar was fixed to the price of gold and the rest of the currencies were pegged to the dollar and a fixed exchange rate. Government officials had to buy or sell securities and transferred gold to maintain the respective fixed exchange rates.

Nations that peg their currencies to other currencies, such as Thailand did before 1997 and Saudi Arabia does today in 2009, still have to do that. When Thailand suffered inflation in the mid-1990s because of a real estate price bubble, the government was forced to buy more reserves to prop up its currency. By 1997, the Thai government ran out of money and was forced to accept an international bailout organized by the International Monetary Fund. The entire process could have been avoided if Thailand had allowed its currency to float in the open market, which it has done more or less since the Asian financial crisis of 1997-1998.

Countries, including the United States, keep official reserves. Most commonly, the reserves are held in the form of gold, foreign currency, and Special Drawing Rights with the International Monetary Fund. Reserves are accumulated when a government requires converting export earnings from the nation’s domestic firms through various other operations meant to insulate an economy from short-term capital flows and through intervention in the foreign exchange market.

To fund its current account deficit, the United States must be a net importer of capital. If the private sector is incapable or unwilling, resulting in downward pressure on the dollar at times and upward pressure on other currencies, foreign central banks often step into the breach. They buy U.S. dollars and sell their own currency. How willing countries are to tolerate volatile currencies (which is how many experience what the G7 euphemistically calls “flexible” exchange rates) depends on numerous factors, including: the strength of domestic financial institutions, sensitivity of exports and inflation to currency appreciation and depreciation, and the significance of the export sector to the overall economy.

That the balance of payments is calculated on a flow basis, not a stock basis, is also a source of confusion. This means that the numbers represent changes in value, not absolute amounts of value. The BOP doesn’t consider inflation. It can’t take into account ho...

Table of contents

- Praise

- Also available from

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- MYTH 1 - The Trade Deficit Reflects U.S. Competitiveness

- MYTH 2 - The Current Account Deficit Drives the Dollar

- MYTH 3 - You Can’t Have Too Much Money

- MYTH 4 - Labor Market Flexibility Is the Key to U.S. Economic Prowess

- MYTH 5 - There Is One Type of Capitalism

- MYTH 6 - The Dollar’s Privileged Place in the World Is Lost

- MYTH 7 - Globalization Destroyed American Industry

- MYTH 8 - U.S. Capitalist Development Prevents Socialism

- MYHT 9 - The Weak U.S. Dollar Boosts Exports and Drives Stock Markets

- MYTH 10 - The Foreign Exchange Market Is Strange and Speculative

- Chapter 11 - Summary and Some Thoughts on the Way Forward

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

- About Bloomberg