![]()

1

Key Characteristics of In Extremis Leaders— and How They Are Relevant in All Organizations

The key characteristics that in extremis leaders display are common among many types of good leaders. For example, competence, trust, and loyalty are leadership imperatives that span a variety of contexts. Nevertheless, when it comes to matters of life and death, leadership assumes a recognizable form: the in extremis pattern. This chapter explores this pattern and describes the key traits that comprise it, drawing on interviews with parachutists, SWAT teams, soldiers (both American and Iraqi), firefighters, and even a tiger hunter. We’ll take a look at what they have to say about what constitutes great leadership in high-risk situations, which often has important implications for leadership in any situation.

Getting Started: Ranking In Extremis Leadership Competencies

One of the simplest yet inherently scientific ways to learn about the nature of leadership in dangerous contexts is to directly compare in extremis leaders who are actively engaged in dangerous activity with more ordinary leaders who are not operating at risk. One group that I interviewed included the most experienced members of the U.S. Military Academy (USMA) sport parachute team, who at the time were parachuting six days a week and served in leadership roles on the team. I then compared what I learned from these interviews with identical interviews that I conducted with senior athletes on other USMA sports teams. The athletes I talked to fell into one of three categories: team sport athletes, individual sport athletes, or competition parachute team members. I was most interested in comparing high- and low-risk sports teams. The rank-ordering of the leadership competencies was intended to represent the athletes’ personal strengths in the context of their particular sport.

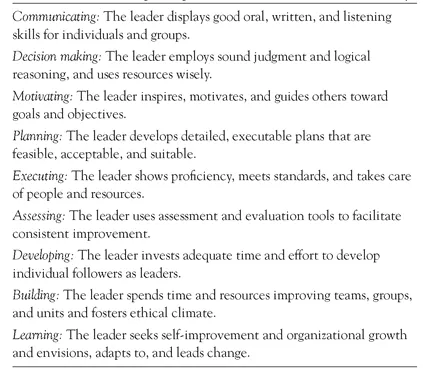

This simple comparison revealed powerful findings about the characteristics of good in extremis leaders. During the interviews, I asked the West Point athletes, who were mostly team captains and other leaders, to rank-order nine leadership competencies that are endorsed by the Army in its leadership doctrine, as shown in Exhibit 1.1. The rest of this chapter describes the results of this survey, which are substantiated by interviews with people working in other high-risk situations.

Exhibit 1.1. Leadership Competencies Ranked in the USMA Survey

In Extremis Leaders Are Inherently Motivated

As you might expect, for leader athletes in both team and individual sports, the competency “motivating” was at the top of the list. After all, winning is about farther, harder, faster. One might assume that in sports with risk to life, motivation would be powerful, even more important. Astonishingly, however, among the members of the national champion competition parachutists, “motivating” ranked second from the bottom—a very significant difference. “Learning” averaged number one on the parachutists’ list.

Using interview data to explore this counterintuitive finding, I inferred two characteristics of the in extremis pattern:

• In extremis contexts are inherently motivating. The danger of the context energizes those who are in it, making cheerleading much less necessary.

• The potential hostility of the context means that those who work there place a premium on scanning their environment and learning rapidly.

It is important to distinguish between the in extremis concept of inherent motivation and the more commonly cited concept of intrinsic motivation. People who are intrinsically motivated are internally driven. Consider these definitions of

intrinsic motivation taken from popular books about the commitment of educators:

“Intrinsic motivation refers to motivation to engage in an activity for its own sake. People who are intrinsically motivated work on tasks because they find them enjoyable.”1

“Intrinsic motivation is the innate propensity to engage one’s interests and exercise one’s capacities, and, in doing so, to seek out and master optimal challenges.”2

“Intrinsic motivation is choosing to do an activity for no compelling reason, beyond the satisfaction derived from the activity itself—it’s what motivates us to do something when we don’t have to do anything.”3

The inherent motivation of in extremis contexts is different from intrinsic motivation: rather than occurring for no compelling reason, it occurs as a result of the most compelling reason, and that’s the consequence of death. Inherent motivation is externally derived from the in extremis context, not the internally derived intrinsic motivation. It is a new way of viewing the leader-follower dynamic in dangerous settings and is the conceptual portrayal of how the environment demands the total focus of the in extremis leader while at the same time motivating the follower.

Powerful motivation is inherent in dangerous contexts. This means that in extremis leaders don’t need to do a lot of cheerleading; they’re not the motivational speaker or high-pressure sales type. People need to be motivated to endure misery or physical challenge, but not through in extremis circumstances where threat of death or injury is high. Drill sergeants sometimes have to yell and scream to get trainees to function. This is usually not the case among combat leaders, because followers are inherently motivated by the grave circumstances of combat.

In Extremis Leaders Embrace Continuous Learning

In extremis situations demand an outward or learning orientation, and this orientation is also heightened by threat. This is a new variation, but is similar in some ways to a well-established concept in the management literature. In a widely cited article in the Journal of Management Studies, noted author Karl Weick refers to an outward focus on crisis as enacted sense making. Weick recognized the dynamic between the excitement people feel in crisis and the need for the leader to add further excitement to the crisis: “Sensemaking in crisis conditions is made more difficult because action that is instrumental to understanding the crisis also intensifies the crisis.” Therefore, it is more important for people in in extremis contexts to focus outward and learn than it is for them to add excitement to the situation through motivation. Weick goes on, “People enact the environments that constrain them. . . . Commitment, capacity, and expectations affect sensemaking during crisis and the severity of the crisis itself.”4

Thus, in extremis leaders need to focus outward on the environment to make sense of it and can actually make matters worse by intensifying people’s fear by trying to motivate them. To Weick, this phenomenon was evidenced in crisis. In extremis leaders are routinely and willingly in circumstances that novices would label as crises, and my findings suggest that Weick’s earlier work may help inform leadership in dangerous settings as well as in organizational crises. Such a parallel will be particularly important in Chapter Two, which directly compares leadership in dangerous situations with conventional business settings.

In Extremis Leaders Share Risk with Their Followers

Another characteristic that sets in extremis leaders apart from other leaders is their willingness to share the same, or more, risk as their followers. This is, of course, partly true because they join their followers in challenging and dangerous circumstances. We found, however, such profound and consistent sharing of risk that it clearly stands out as a defining characteristic of in extremis leaders.

Leaders themselves expressed powerful feelings about shared risk; for example, consider the following comments made from a SWAT team leader and a tiger hunter:

If you put the plan together and you’re not comfortable being up there with a foot through the door, what the hell is up?

Special Agent James Gagliano, SWAT team leader, New York City Office of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

I assume twenty times the risk [of my team, although] . . . there is some equal risk in the field. Any of us could fall off the elephant, and any of us could be thrown from the jeep, and we did get injured, all of us, and hurt on a daily basis. There wasn’t anybody that didn’t come back bloodied or badly bruised or hurt. We have a seventy-pound tripod on top of an elephant, it sometimes got hinged against a tree and the tripod will fall. . . . Every day we got hurt. So I went through like ten bottles of Advil, which I gave to my team to help them get through that.

Carole Amore, professional videographer, expedition leader, and author of Twenty Ways to Track a Tiger

These interviews also made it clear that this shared risk was not merely a form of leader hubris, showboating, or simple impression management. Rather, it’s part of the in extremis leader’s style or technique. It profoundly affected the followers; followers recognized it, knew what it represented in the heart and character of their leader, and deeply respected their leader as a result. This phenomenon was acute on the battlefields of Iraq, as these American soldiers described the importance of their leaders’ sharing the risk the soldiers faced:

You have to learn confidence in your leaders and trust in their judgment. They are not going to throw you out into something that they wouldn’t put themselves in as well.

U.S. soldier, Third Infantry Division, Baghdad, Iraq

I think that the only difference in their roles was that they got a little more information a little sooner than the rest of us. Other than that, they weren’t really that much different than anybody else. . . . Other than seeing what was on the collar [their rank insignia], it’s hard to decipher who was who. . . . The officers here, they showed leadership and they get out there and do the same things that me or him were doing.

U.S. soldier, Third Infantry Division, Baghdad, Iraq

Conversely, soldiers who found their leaders unwilling to share the risk had little will, and lost motivation, as in the case of this captured Iraqi soldier:

The leader . . . was a lieutenant colonel. An older man, forty-five, forty-six, forty-eight years of age. He was a simple person, but the instruction come from the command in Baghdad. Like, “do this,” but he doesn’t do that, and he ran away. . . . He told us if you see the American or the British forces, do not resist.

Captured Iraqi soldier, Um Qasr, Iraq

The common practice of providing business leaders with buyout plans, generous rollover contracts, or golden parachutes does little to inspire follower confidence. Certainly it puts business risk, compared to risk of life, in perspective. When performance means life or death, the best leaders don’t wear parachutes unless their followers do too.

In Extremis Leaders Have a Common Lifestyle with Their Followers: There’s No Elitism

A fourth unique characteristic of the in extremis pattern emerged when we asked interviewees about their remuneration and lifestyle. In an era where there are entire conferences devoted to executive compensation, it was refreshing to focus on authentic leaders who lacked materialism and instead focused on values.

When I asked public sector employees such as police officers and soldiers about the nature of their pay structure, the leader’s pay and the follower’s pay were unequal but uniformly modest. I found consistently that most in extremis leaders earn at most an average wage but that they felt it was sufficient for their needs. This made sense to me and my colleagues who also interviewed these people. In contexts that routinely threaten the lives of the leader and the led, value attached to life is morally superior to value attached to material wealth. Pay should take a backseat to other concerns. Economists might deconstruct this phenomenon differently with respect to public service jobs, arguing that the availability and skill sets of such work drive wages down. Perhaps. But the often overlooked mechanism is the irrelevance of symbolic value in the face of danger.

Money has no meaning. Even future rewards or punishments have little meaning when the promise of a future is uncertain.

Current leadership theory recognizes that symbolic value is only applicable in limited circumstances. James MacGregor Burns initially developed the notion of transformational leadership, based largely on a charismatic leader establishing vision, a way ahead.5 This contrasted with other theories that together were characterized as transactional, based on leader-follower transactions such as giving pay and rewards and establishing perceptions of equity and fairness. The idea that organizations could be changed by a transformational leader took root, was elaborated by Bernard Bass and others, and is a dominant theory in the art and science of leadership today.6

Earlier writers, however, presumed that a transformational approach was due to either a leader characteristic such as charisma or a leader approach such as visioning. For those who understand the dynamics of dangerous settings, it’s clear that the immediate threat places value on human life and strips away the value inherent in transactional leadership. In fear of their life...