![]()

1

Closing the Gap

Back in the 1920s and 1930s, Richard W. Schabacker wrote several books that were based on Dow theory. He hypothesized successfully that certain patterns in the major averages were also relevant to individual stocks. His brother-in-law Robert D. Edwards continued his work. Many in our generation are familiar with the technical work of Edwards and his partner John Magee (Magee, 1994, ix–xv). Together, they are considered the fathers of modern technical analysis. As we know, technical analysis is a snapshot of market participants’ collective behavior. Because we are dealing with human emotions, these patterns of collective behavior are continually repeated. They can be recognized and then used to anticipate future moves in the markets. These patterns can be further broken down into naturally recurring sets of waves and calculations.

The basic structure of financial markets lies in a catalog of repeatable patterns uncovered by Ralph Nelson Elliott, refined over the years by other well-known Elliotticians, including Robert Prechter Jr. The Wave Principle represents a good pattern recognition system. No two patterns are ever alike, but they all have repeatable tendencies. Inside these waves are universal calculations, which are measured in terms of price and time. These measurements are driven by Fibonacci relationships. Much of the research on the time element is derived from the work of W. D. Gann, who should be considered the founding father of modern time studies. From Gann, modern Fibonacci analysts have done an excellent job of simplifying the methodology so traders can use it as an everyday discipline.

Édouard Anatole Lucas

Famous for his research in number theory, François Édouard Anatole Lucas is the 19th century French mathematician for whom the Lucas Series is named. It was while working with the Fibonacci series (one he is often credited with naming) that he discovered the closely related series of numbers. While defined nearly identically to the Fibonacci series (each number is the sum of the previous two, except for the first two members of the series; f(n) = f(n-2) + f(n-1)), Lucas numbers start with 2 and 1 rather than 1 and 1. While seemingly a small difference, the variation is clear:

Lucas Series: 2, 1, 3, 4, 7, 11, 18, 29, 47, 76, 123, 199, 322, 521, ...

Fibonacci Series: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, 233, 377, ...

As is true for any Fibonacci-like series, the ratio of successive Lucas numbers converge to the golden ratio phi,

(1.618 ...). Moreover, the two series are related in many other ways with ongoing research still in progress today. According to Clark Kimberling, Professor of Mathematics, University of Evansville, to find the following Lucas-Fibonacci identities to be true, write the two sequences as L(0), L(1), L(2), . .. and F(0), F(1), F(2), . . . .then for all nonnegative integers n:

L(n), = F(n+2) − F(n−2)

L(4n) + 2 = (L(2n))∧2

L(4n) − 2 = 5(F(2n))∧2

F(n + m) + F(n − p) = F(n)L(m)

if m is even

L(n − 1)L(n + 1) + F(n − 1)F(n + 1) = 6(F(n))∧2.

Forty-seven such identities are given by Verner E. Hoggatt, Jr. in his book Fibonacci and Lucas Numbers (Hoggatt 1969, 59-60).

The Elliott methodology relies heavily on the Fibonacci relationships to the point where the trader really can’t use one without the other. Because the Wave Principle relies on Fibonacci calculations, it would make sense that those who use Fibonacci retracements would recognize patterns in terms of Elliott waves. This book incorporates the time principle into the Fibonacci–Elliott ways of thinking and provides traditional technical analysis. I find, however, that the Elliott–Fibonacci community has left out an important part of the equation. Some Fibonacci calculations are so complex that they are not practical to use. Traders use Fibonacci calculations because they are practical pattern-recognition tools. Yet, what if some calculations are too complex to be recognized easily? If it doesn’t work, what do we do instead? How do we fill in the gap? This book, to a degree, closes that gap.

Most books of this genre cover Elliott and Fibonacci, as well as sacred geometry. This book enhances most of these studies. The methodology presented here relies heavily on the Lucas series of mathematics. French mathematician Edouard Lucas (1842–1891) discovered this series, which is a derivative of the Fibonacci sequence. It is mentioned briefly in other books, and it is here where this series is presented in great detail. Although I am not the first to present Lucas to the financial community, I believe its profound influence on many financial charts in all degrees of trend has been greatly misunderstood and understated. This book attempts to rectify that. Lucas’s work does not supersede Fibonacci’s; it complements it. What most people in the trading community don’t realize is the degree to which it complements it. According to the research presented here, you will see how often it does. The purpose of using the time dimension is to gain a very important tool in the pattern recognition game.

An airplane pilot would never think of taking off in a plane that was not equipped with instruments that would enable him or her to fly or land it in spite of poor visibility. As challenging as financial markets are, using technical analysis as a pattern recognition system without the time dimension is like attempting to land a plane in zero visibility.

Before switching to “instruments,” we must be able to navigate in good weather. Basic navigation of financial markets begins with an understanding of the Wave Principle. The Wave Principle gives the trader a good start at pattern recognition. Those of you trained in the Edwards and Magee school of technical analysis can compare and contrast the two methodologies. This book uses the Wave Principle only as a guide because it is fairly complex and not totally reliable in real time.

When we look at the waves, we can get an idea of where we are in a trend. We can also have an idea if we are in the main trend or in a move that technically “corrects” that trend. Sometimes a correction is so large in relation to the main trend that we really don’t know whether the larger trend has changed. This is one of the black holes in the Wave Principle that this book intends to clarify.

There are two basic patterns of waves. The first are known as “impulse waves,” which is the larger degree prevailing trend. The other is known as “corrective waves,” which move counter to the main trend. Each has its own distinct set of characteristics. In this chapter, I only cover the basics as a review of materials you may have read elsewhere. Later, I will show you how to recognize an impulse or corrective wave by exclusively understanding the number sequences.

IMPULSE WAVES

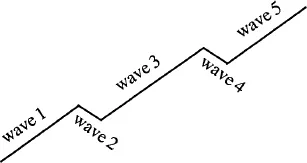

Impulse waves have their own unique characteristics. The larger prevailing trend is considered to be an impulse wave, which you can recognize as it moves in a 5-wave sequence. Impulse waves can also move in 9- or 13-wave patterns. There are only three iron laws of impulse waves according to Prechter (Prechter 1999, 30):

1. Wave 3 is never the shortest wave.

2. Wave 2 never retraces more than 99 percent of wave 1.

3. Wave 4 does not overlap the territory of wave 1.

IMPULSE WAVES

1. Wave 3 is never the shortest wave.

2. Wave 2 never retraces more than 99 percent of wave 1.

3. Wave 4 does not overlap the territory of wave 1.

Let’s clear up some of the confusion surrounding these rules. Some think the third wave is always the largest wave, but this simply is not the case. Generally, the tendency is for wave 3 to be the largest wave, but the rule is that it can’t be the shortest wave. If you are counting waves and the middle wave is the smallest, something else is going on. That particular wave might be an extension of the first wave, but it isn’t a third wave (Figure 1.1).

The other controversy surrounds fourth waves. According to some in the Elliott community, they do not allow for any overlap of the first and fourth waves, but I’ve seen many instances where wave 4 touches, grazes, or slightly overlaps wave 1. I think you need to apply common sense to the situation. If you have a fourth wave that makes an obvious violation into first-wave territory, it isn’t a fourth wave. If you’ve had a first wave, a retracement second wave, and a third wave that makes a decent advance; and then you have a pullback that grazes first-wave territory before turning up, I think you can make a case for the pullback being the fourth wave.

Another characteristic of impulse waves is the Rule of Alternation. This is not an iron law, but rather a guideline. The Rule of Alternation suggests that if the second-wave retracement takes the form of a sharp correction, the fourth wave is likely to be a flat correction. Another way in which this rule manifests itself is that when the first wave is the largest wave, the fifth wave will be the smallest. In a larger move, if one set of five has the third wave as the extension, the next round will have either the first or the fifth wave as the extended wave (Prechter, 1999, 61).

Extensions are another important characteristic of impulse waves. This means that of waves 1, 3, or 5, one will be considerably larger than the other two. Extensions are hard to count while they are in progress, and the exact count is not readily apparent until late in the move. The time cycles clear up much of the confusion and allow traders or analysts a better roadmap to determine more easily where they are in the bigger scheme of things.

There are sets of common relationships in an impulse sequence that are Fibonacci based. The most common tendency is for the third wave to be the extended wave, and many times it will measure 1.618 or 2.618 times the length of wave 1 as measured from the bottom of wave 2 (Prechter 1999, 125–138). In lower probability cases, wave 3 may even measure 4.23 times the length of wave 1.

When wave 3 is the extended wave, the tendency is for waves 1 and 5 to have a .618/1.618 relationship to each other. In rare cases, wave 5 can be a 2.618 extension of wave 1. Recently, we had a situation in the XAU where wave 5 was a 2.618 extension of wave 1 and wave 3 was not the shortest wave. When wave 5 extends, it usually measures 1.618 times the length of waves 1 to 3, with wave 1 being the smallest wave. When wave 1 extends, it will usually measure 1.618 times the length of waves 3 to 5, with wave 5 being the smallest wave. In rare cases, we can have a double extension where waves 3 and 5 are both twin 4.23 extensions of wave 1.

The best way to recognize an extended wave is to observe how the progression begins. Once we get a new trend, we’ll have a first wave up, a retracement, and another leg up. If the second retracement violates the territory of the very first wave in the sequence, we know by the iron law of fourth waves that this can’t be a fourth wave. It must be the start of an extension or larger move. How do we know that it is not a corrective move? Watch the volume patterns. At all times, we will use other indicators to confirm a wave count. If we are in an uptrend, the down days compared to the up days will be lower volume on average. For instance, if we’ve been through a long downtrend where sentiment became unusually negative, the trend going in the new direction will start to build decent volume days and the pullbacks will be of lighter volume. A lighter volume wave that slightly overlaps a first wave up is likely to be corrective, counter to the new trend, and part of an extension going in the new direction. The time dimension will also give us a good clue as to the underlying direction. I will cover that in a later chapter.

CORRECTIVE WAVES

Corrective waves have their own unique set of characteristics that differentiate them from impulse waves. A wave is corrective when it moves counter to the trend. There are two types of corrective waves. One family consists of sharp corrections, the other family of flat corrections. You may consider triangles to be another subset, but technically they are part of the flat family.

CORRECTIVE WAVES

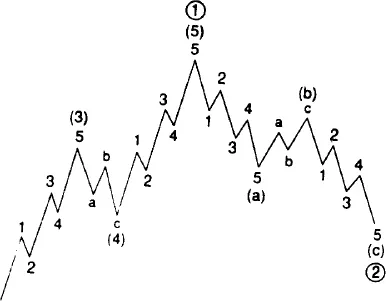

Corrective waves have their own unique set of characteristics that differentiate them from impulse waves (please see Figure 1.2 for a look at the complete wave sequence). A wave is corrective when it moves counter to the trend. There are two types of corrective waves. One family consists of sharp corrections, the other family of flat corrections. You may consider triangles to be another subset, but technically they are part of the flat family.

Sharp corrections normally fall into a 5–3–5 pattern of waves. They are labeled differently from impulse waves and use letters as opposed to numbers. An ABC correction will contain five small waves moving counter to the trend followed by a small, sideways or triangle correction, followed by five more waves. The way to recognize these waves is that they violate the overlap rule where the fourth wave falls deep into the territory of the first wave. The best way to recognize sharps is that they are very choppy.

If you don’t understand waves and have no real plan to do so, the best way to understand corrective moves is by their choppiness or lack of structure. Corrective waves are also characterized by an average lower volume than th...