![]() PART 1

PART 1

Basic Concepts![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction to Mobile and Wireless Networks 1

1.1. Introduction

Wireless networks in small or large coverage are increasingly popular as they promise the expected convergence of voice and data services while providing mobility to users. The first major success of wireless networks is rendered to Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11), which opened a channel of fast and easy deployment of a local network. Other wireless technologies such as Bluetooth, WiMAX and WiMobile also show a very promising future given the high demand of users in terms of mobility and flexibility to access all their services from anywhere.

This chapter covers different wireless as well as mobile technologies. IP mobility is also introduced. The purpose of this chapter is to recall the context of this book, which deals with the security of wireless and mobile networks. Section 1.2 presents a state of the art of mobile cellular networks designed and standardized by organizations such as ITU, ETSI or 3GPP/3GPP2. Section 1.3 presents wireless networks from the IEEE standardization body. Section 1.4 introduces Internet mobility. Finally, the current and future trends are also presented.

1.2. Mobile cellular networks

1.2.1. Introduction

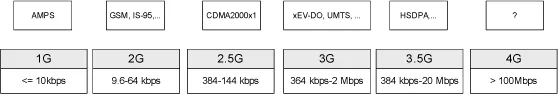

The first generation (1G) mobile network developed in the USA was the AMPS network (Advanced Mobile Phone System). It was based on FDM (Frequency Division Multiplexing). A data service was then added on the telephone network, which is the CDPD (Cellular Digital Packet Data) network. It uses TDM (Time Division Multiplexing). The network could offer a rate of 19.2 kbps and exploit periods of inactivity of traditional voice channels to carry data. The second generation (2G) mobile network is mainly GSM (Global System for Mobile Communications). It was first introduced in Europe and then in the rest of the world. Another second-generation network is the PCS (Personal Communications Service) network or IS-136 and IS-95; PCS was developed in the USA. The IS-136 standard uses TDMA (Time Division Multiple Access) while the IS-95 standard uses CDMA (Code Division Multiple Access) in order to share the radio resource. The GSM and PCS IS-136 employ dedicated channels for data transmission.

The ITU (International Telecommunication Union) has developed a set of standards for a third generation (3G) mobile telecommunications system under the IMT-2000 (International Mobile Telecommunication-2000) in order to create a global network. They are scheduled to operate in the frequency band around 2 GHz and offer data transmission rates up to 2 Mbps. In Europe, the ETSI (European Telecommunications Standards Institute) has standardized UMTS (Universal Mobile Telecommunications Systems) as the 3G network.

The fourth generation of mobile networks is still to come (in the near future) and it is still unclear whether it will be based on both mechanisms of cellular networks and wireless networks of the IEEE or a combination of both. The ITU has stated the flow expected by this generation should be around 1 Gbps static and 100 Mbps on mobility regardless of the technology or mechanism adopted.

The figure below gives an idea of evolving standards of cellular networks. Despite their diversity, their goal has always been the same; to build a network capable of carrying both voice and data respecting the QoS, security and above all reducing the cost for the user as well as for the operator.

1.2.2. Cellular network basic concepts

a) Radio resource

Radio communication faces several problems due to radio resource imperfection. In fact the radio resource is prone to errors and suffers from signal fading. Here are some problems related to the radio resource:

– Power signal: the signal between the BS and the mobile station must be sufficiently high to maintain the communication. There are several factors that can influence the signal (the distance from the BS, disrupting signals, etc.).

– Fading: different effects of propagation of the signal can cause disturbances and errors. It is important to consider these factors when building a cellular network.

To ensure communication and to avoid interference, cellular networks use signal strength control techniques. Indeed, it is desirable that the signal received is sufficiently above the background noise. For example, when the mobile moves away from the BS, the signal received subsides. In contrast, because of the effects of reflection, diffraction and dispersion, it can change the signal even if the mobile is close to the BS. It is also important to reduce the power of the broadcast signal from the mobile not only to avoid interference with neighboring cells, but also for reasons of health and energy.

As the radio resource is rare, different methods of multiplexing user data have been used to optimize its use:

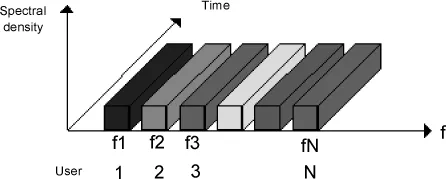

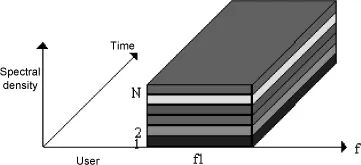

– FDMA (Frequency Division Multiple Access) is the most frequently used method of radio multiple access. This technique is the oldest and it allows users to be differentiated by a simple frequency differentiation. Indeed, to listen to the user N, the receiver considers only the associated frequency fN. The implementation of this technology is fairly simple. In this case there is one user per frequency.

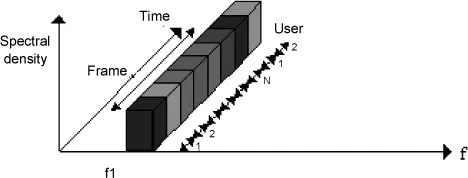

– TDMA (Time Division Multiple Access) is an access method which is based on the distribution of the radio resource over time. Each frequency is then divided into intervals of time. Each user sends or transmits in a time interval from which the frequency is defined by the length of the frame. In this case, to listen to the user N, the receiver needs only to consider the time interval N for this user. Unlike FDMA, multiple users can transmit on the same frequency.

– CDMA (Code Division Multiple Access) is based on the distribution code. It is spread by a code spectrum allocated to each communication. In fact, each user is differentiated from the rest of users with a code N allocated at the beginning of its communication and is orthogonal to the rest of the codes related to other users. In this case, to listen to the user N, the receiver has to multiply the signal received by the code N for this user.

The traffic uplink and downlink on the radio resource is managed by TDD (Time Division Duplex) or FDD (Frequency Division Duplex) multiplexing methods as the link is symmetric or asymmetric.

– OFDM (Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing) is a very powerful transmission technique. It is based on the idea of dividing a given high-bit-rate datastream into several parallel lower bit-rate streams and modulating each stream on separate carriers, often called subcarriers. OFDM is a spectrally efficient version of multicarrier modulation, where the subcarriers are selected such that they are all orthogonal to one another over the symbol duration, thereby avoiding the need to have non-overlapping subcarrier channels to eliminate intercarrier interference. In order to have multiple user transmissions, a multiple access scheme such as TDMA or FDMA has to be associated with OFDM. In fact, an OFDM signal can be made from many user signals, giving the OFDMA multiple access [STA 05]. The multiple access has a new dimension with OFDMA. A downlink or uplink user will have a time and a subcarrier allocation for each of their communications. However, the available subcarriers may be divided into several groups of subcarriers called subchannels. Subchannels may be constituted using either contiguous subcarriers or subcarriers pseudorandomly distributed across the frequency spectrum. Subchannels formed using distributed subcarriers provide more frequency diversity. This permutation can be represented by Partial Usage of Subcarriers (PUSC) and Full Usage of Subcarriers (FUSC) modes [YAH 08].

b) Cell design

A cellular network is based on the use of a low-power transmitter (~100 W). The coverage of such a transmitter needs to be reduced, so that a geographic area is divided into small areas called cells. Each cell has its own transmitter-receiver (antenna) under the control of a BS. Each cell has a certain range of frequencies. To avoid interference, adjacent cells do not use the same frequencies, as opposed to two non-adjacent cells.

The cells are designed in a hexagonal form to facilitate the decision to change a cell for a mobile node. Indeed, if the distance between all transmitting cells is the same, then it is easy to harmonize the moment where a mobile node should change its cell. In practice, cells are not quite hexagonal because of different topography, propagation conditions, etc.

Another important choice in building a cellular network is the minimum distance between two cells that operate at the same frequency band in order to avoid interference. In order to do so, the cell’s design could follow different schema. If the schema contains N cells, then each of them could use K/N frequencies where K is the number of frequencies allocated to the system.

The value of reusing frequencies is to increase the number of users in the system using the same frequency band which is very important to a network operator.

In the case where the system is used at its maximum capacity, meaning that all frequencies are used, there are some techniques to enable new users in the system. For instance, adding new channels, borrowing frequency of neighboring cells, or cell division techniques are useful to increase system capacity. The general principle is to have micro and pico (very small) cells in areas of high density to allow a significant reuse of frequencies in a geographical area with high population.

c) Traffic engineering

Traffic engineering was first developed for the design of telephone circuit switching networks. In the context of cellular networks, it is also essential to know and plan to scale the network that is blocking the minimum mobile nodes, which means accepting a maximum of communication. When designing the cellular network, it is important to define the degree of blockage of the communications and also to manage incoming blocked calls. In other words, if a call is blocked, it will be put on hold, and then we will have to define what the average waiting time is. Knowing the system’s ability to start (number of channels) will determine the probability of blocking and the average waiting time of blocked requests.

What complicates this traffic engineering in cellular networks is the mobility of users. In fact, a cell will handle, in addition to new calls, calls transferred by neighboring cells. The traffic engineering model becomes more complex. Another parameter that is even more complicating fo...