![]()

PART One

The Challenges of Changes and Crises

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Discontinuity Challenge

Wayne H. Wagner

Principal, OM♦NI

The twists and tangles of the 2008 credit crunch will long be remembered. While this chapter does not address that specific discontinuity, it does focus on discontinuities in general. From a longer time perspective, we see that discontinuities occur frequently, suggesting that in addition to applying our experience and running our models that work in “normal” times, we need to prepare to face the inevitable discontinuity environments.

THINKING ABOUT DISCONTINUITIES

Q: How’s your day going?

A: Same old, same old.

Most days, things go on today as they did yesterday. A very large portion of our behavior is rooted in the almost always correct assumption that past experience will guide us through the next day.

Almost always correct? Yes, but what about those occasions when something crosses our path that is new and dangerous, something wholly unlike what we encountered in the past?

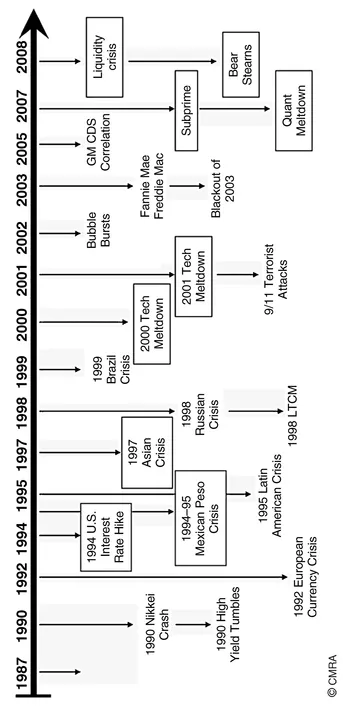

Exhibit 1.1 shows how these “unexpected” shocks seem to occur every few years.1 Looking further back, we can find serious U.S. stock market/ financial panics in 1797, 1812, 1819, 1823, 1825, 1837, 1847, 1857, 1866, 1893, 1907, 1918, 1929 . . . you get the picture. As Rahl shows, these disruptive events are not the outliers we think they are, but rather common events that occur far more frequently than we recall. There are a lot of discontinuities, they always surprise many, they wreak havoc on the financially weak, and, most importantly, once the markets and the economy are sufficiently wrung out, they go away.

EXHIBIT 1.1 "Unexpected" Financial Shocks—Once in a Lifetime Crises Seen to Occur Every Few Years .

Source: Courrecy of Leslie Rahl at Capital Market Risk Advisors (http://www.cmra.com/crises.php)

Despite the frequency of discontinuities and the major effects they can have on the economy and our accumulated wealth, most investment thinking is based on consideration of data gathered during more normal cause-and-effect economic times. There is a very strong reason for this focus: It isn’t really possible to do otherwise. We can paint scenarios of dire conditions, but we cannot usefully judge their likelihood, their timing, or their severity. Faced with our inability to deal with the unknowable, our focus naturally turns to the more intelligible.

Thus, the study of economic value necessarily focuses on the observables (i.e., history), and especially the massive data generated by the continuous unfolding of economic and market history. But out there lay broader possibilities perfectly capable of upsetting our best-laid plans. Surprise is always around the corner. H. L. Mencken put it well when he said, “Penetrating so many secrets, we cease to believe in the unknowable. But there it sits nevertheless, calmly licking its chops.”

Where do these discontinuities arise? Actually, very few sources seem to account for the majority: natural disasters; large financial failures, most often arising from overextended leverage and expectations (aka greed); and the unintended consequences of political tinkering. Allan Bloom, in The Closing of the American Mind,2 points out the supremacy of politics over economics:

The market presupposes the existence of law and the absence of war. . . . Political science is more comprehensive than economics because it studies both peace and war and their relations . . . the preservation of the polity continuously requires reasoning and deeds which are “uneconomic” or “inefficient.” Political action must have primacy over economic action, no matter what the effect on the market.

DECISION MAKING IN NORMAL TIMES

We can characterize most active investment managers as intuitive thinkers who search for significant facts that stand out from the mass of observation—that is, hidden value. The danger for the intuitive thinker is that discontinuity events overwhelm the economic thinking that must prevail during the everyday course of events. In discontinuous times, everything’s an outlier, and hidden value becomes deeply and obscurely hidden.

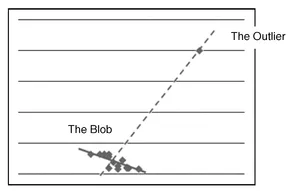

Quantitative managers, in contrast, are systematic thinkers who focus on “normal” tendencies like orderly effects and small systemic inefficiencies, which are often obscured from the intuitors within the mass of data. But the equations don’t work when we encounter the deviant outlier observations. Statisticians recognize that the importance of a data point rises with the square of its distance from the mean observation. Any statistical analysis using an observation out of the “normal” range will fit a regression line right through that deviant point. It is as though there were only two observations: the deviant point and the blob of the remaining observations, within which all normally significant relationships are insignificant by comparison.

In Exhibit 1.2, the solid line through the blob represents normal relationships, while the dotted line represents the effect of adding an extreme outlier to the regression data.

EXHIBIT 1.2 Effect of Adding an Extreme Outlier to the Regression Data

For this reason, most statistical analyses throw away obviously deviant data. But how can that be justified in the context of portfolio management? It sounds absurd to pretend that these outlier events never happen, yet our primary tools are useful only for investigating economic relationships rather than, as Bloom suggests, the realm of political events.

Well, this is embarrassing! We’re damned if we include the deviant data, and damned if we don’t. Unless we have some operative model, either intuitive or statistical, of how the world works in normal times, we might as well use astrology to build portfolios. So the correct course of action seems to be to set aside the impenetrable deviants, but by all means not to forget them. The danger, of course, is that once we discard the deviant data, we frequently forget or sublimate that it ever existed. And the more our “normal times” thinking makes us rich, and the longer normal times last, the more inclined we are to forget the unknowable, which is calmly licking its chops.

Keith Ambachtsheer points out in Chapter 2 that it is all too easy to get caught up in the excitement and romance of making truly serious money. It is useful here to reflect on a July 2007 quote from Charles Prince, the ex-chairman and CEO of Citigroup:

When the music stops, in terms of liquidity, things will get complicated. But as long as the music is playing, you’ve got to get up and dance. We’re still dancing. . . . 3

Prince seems supremely confident in his ability to know when to exit, but with everyone planning to stay as late as they can, he clearly underestimated how quickly conditions can change. Four months later, the music stopped and Mr. Prince was unceremoniously ushered out the door.

Call this temptation the financial dance of death. It’s easy to string along while the money’s flowing in, but how do you know when to stop? Those who leave the dance too early leave money on the table and initially look incompetent. However, a fully committed player like Mr. Prince finds that he can’t escape when the building’s on fire and everyone wants out at the same time. Envision a whole symphony hall overwhelmed with panic. Now envision the same panic in the trading rooms of Wall Street. As we’ve seen, hardly anybody knows how to call that timing very well.

“Haven’t we been here before?” you might ask. In retrospect, all the dance steps to ruin look familiar. But each time the players are different, the lyrics sound new, and there’s money to be made. We’ve seen junk bonds bring down the S&Ls, we’ve seen Russian bonds bring down Long Term Capital Management, but we’ve never experimented with junk mortgages before, so it looks different—at first glance. The leverage gets geared up, the duration of the assets is mismatched to the liabilities, and the comeuppance generates an illiquidity trap. In this game of musical chairs, all the chairs disappear at once while the music is still playing. “Nobody rings a bell when it’s time to sell,” says the wise old Wall Street adage.

It’s easy to scapegoat Charles Prince as a “greedy” Wall Streeter, but all of us can be entranced by the siren’s song.

The above excesses can be summed up as a slowly accumulating deficit in adult supervision, common sense, skepticism, ethical concern, and good, old-fashioned prudence. As often happens in booms, the kids, the ones who didn’t live through the last debacle, shouldered the adults aside or impressed them too much. It’s happened before and it will happen again.

TALEB’S BLACK SWANS

Nicholas Taleb hardly needs introduction to the readers of this book. His work focuses on discontinuities, which he identifies as “black swans.” Taleb describes a black swan as “a highly improbable event with three principal characteristics: It is unpredictable; it carries a massive impact; and, after the fact, we concoct an explanation that makes it appear less random, and more predictable, than it was.”4

In a recent Web article,5 highly recommended to the reader, Taleb focuses on the problem of identifying risks when one cannot rely on conventional statistical methods.

Investment professionals are accustomed to taking risks in order to enhance expected returns. But Taleb points out that we can never correctly identify all the risks. Taleb describes risks that cannot be described by “normal” databases, and that involve higher levels of risks that cannot even be defined by standard methods. They may even involve risks that have never occurred—indeed, that based on our observable data would be considered impossible.

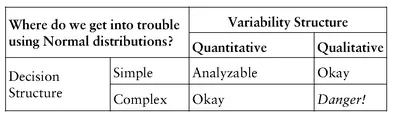

Taleb lays out a 2 × 2 decision table, where one axis is the decision type and the second axis characterizes two structures of variability:

Source: Taleb (see note 4).

Decisions break into two groups, which Taleb calls simple and complex. Simple decisions are true/false, win/lose on the flip of a coin or the payoffs from tossing dice. Complex decisions are situations where you care not only about the frequencies, but also the impact.

Variability structures are similarly divided into simple and complex, or very distinctly quantitative versus qualitative. The quantitative structure corresponds to “random walk”-style randomness found in statistics textbooks. Complex structures embed random jumps as well as random walk elements—the kind of distributions Mandelbrot famously brought to our attention.6

Taleb points out that the problems lie in the confluence of complex decisions and random jump elements. It’s here that black swans bite most viciously.

Consider the dual meaning of the word normal. As a proper noun, capital-N, Normal, it specifically refers to a body of statistical knowledge developed around the delightful mathematical properties of the Gaussian distribution. But the use of the name “normal” probably comes to the statistical world from general usage, “being approximately average or within certain limits.” While there are many places where normal experience is Normally distributed, we fool ourselves—and our clients—when we forget that much of economic life is distinctly abnormal.

Taleb points out that students of statistics approach a problem by assuming a probability structure, typically with a known probability distribution, in all likelihood a Gaussian, Normal distribution. But the critical problem is not making computations once you know the probabilities, but finding the true distribution.

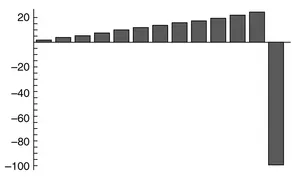

EXHIBIT 1.3 Anatomy of a Blowup

Source: Taleb (see note 4).

Low-probability events that carry large impacts may be difficult to compute from past data. Our empirical knowledge about the potential contribution of rare events will not, then, prepare us for black swan events. Risk is one word but not one number. Variance, skewness, and kurtosis (fat tails) are important. So is the application of risk-scenario analysis that illuminates survivability, best outcome, and breakeven analysis.

Exhibit 1.3 is Taleb’s chart describing a blowup. In the Edge article, Taleb calls this his classical metaphor:

A turkey is fed for a 1000 days—every day confirms to its statistical department that the human race cares about its welfare “with increased statistical significance.” On the 1001st day, the turkey has a surprise.

A big problem for investors is that we can experience a long sequence of normal events before we run into these fat-tail events. We get lulled into the complacency of “a new era.” Furthermore, the more our “normal times” experience makes us rich, the more inclined we are to forget that the unknowable is still out there—still calmly licking its chops.

WHERE WE GO WRONG

Lies, Damn Lies, and Statis...