Part I

Understanding the Fundamentals of Electronics

In this part . . .

Do you ever wonder what makes electronic devices tick? Are you ever curious to know how speakers speak, motors move and computers compute? Well, then, you’ve come to the right place!

In the chapters ahead, we explain exactly what electronics is, what it can (and does) do for you and how all sorts of electronic things work. But don’t worry. We don’t bore you with long essays involving physics and mathematics. We use analogies and down-to-earth examples to make understanding electronics easy – fun, even. And while you’re enjoying yourself, you’re discovering how electronic components work and combine forces to make amazing things happen.

Chapter 1

What Is Electronics and What Can It Do for You?

In This Chapter

Seeing electric current for what it really is

Recognising the power of electrons

Using conductors to go with the flow (of electrons)

Making the right connections with a circuit

Controlling the destiny of electrons with electronic components

Applying electrical energy to loads of things

If you’re like most people, you probably have some idea about what electronics is. You’ve been up close and personal with lots of so-called consumer electronics devices, such as iPods, stereo equipment, personal computers, digital cameras and televisions, but to you, they may seem like mysteriously magical boxes with buttons that respond to your every desire.

You know that underneath each sleek exterior nestles an amazing assortment of tiny components connected together in just the right way to make something happen. And now you want to understand how.

In this chapter, you discover that electrons moving in harmony constitute electric current, which is shaped by electronics. You take a look at what you need to keep the juice flowing, and you also get an overview of some of the things you can do with electronics.

Just What Is Electronics?

When you turn on a light in your home, you’re connecting a source of electrical energy (usually supplied by your power company) to a light bulb in a complete path, known as an electrical circuit. If you add a dimmer or a timer to the light bulb circuit, you can control the operation of the light bulb in a more interesting way than simply switching it on and off.

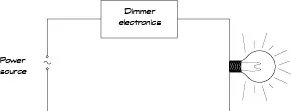

Electrical systems, like the circuits in your house, use a standard electric current to make things such as light bulbs work. Electronic systems take this a step further: they control the electrical current, changing its fluctuations, direction and timing in various ways in order to accomplish a variety of functions, from dimming a light bulb to communicating with satellites (take a look at Figure 1-1). This control is what distinguishes electronic systems from electrical systems.

Figure 1-1: The dimmer electronics in this circuit control the flow of electric current to the light bulb.

To understand how electronics controls electricity, you need to first understand what electricity is and how it powers things like light bulbs.

Understanding Electric Current

Electric current is the flow of electrical charges carried by unbelievably small particles called electrons. So what on earth are electrical charges, where exactly do you find electrons and how do they move around? You find the answers by taking a peek inside the atom.

Getting a charge out of electrons

Atoms are the natural building blocks of everything. They’re so tiny that you can find millions of them in a single speck of dust – so you can imagine how many exist in your average sumo wrestler! Electrons are found in every single atom in the universe, outside the atom’s centre, or nucleus. All electrons have a negative electrical charge and are attracted to positively charged particles, known as protons, which exist inside the nucleus. Electrical charge is a kind of force within a particle, and the words ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ are somewhat arbitrary terms used to describe the two different forces that exhibit opposite effects. (We can call them ‘north’ and ‘south’ or ‘Tom’ and ‘Jerry’ instead, but those names are already taken.)

Under normal circumstances, an equal number of protons and electrons reside in each atom, and the atom is said to be electrically neutral. The attractive force between the protons and electrons, known as an electromagnetic force, acts like invisible glue, holding the atomic particles together, much as the gravitational force of the earth keeps the moon within sight. The electrons closest to the nucleus are held to the atom with a stronger force than the electrons farther from the nucleus, and some atoms hold on to their outer electrons with a vengeance whereas others are a bit more lax.

Moving electrons in conductors

Materials such as air and plastic, in which the electrons are all tightly bound to atoms, are insulators – they don’t like to let their electrons move and so they don’t easily carry an electric current. However, other materials, like the metal copper, are conductors because they have ‘free’ electrons wandering between the atoms, normally moving around at random. When you give these free electrons a push, they all tend to move in one direction and, hey presto, you have an electric current. This flow appears to be instantaneous because all those free electrons, including those at the ends, move at the same time.

A coulomb is defined as the charge carried by 6.24 x 1018 (that’s 62...