![]()

1

FIXING MONEY PROBLEMS

When I started writing about finance, the world according to Wall Street was promoting something called the “efficient markets theory.” In a nutshell, this theory contends that the day-to-day price movements of stocks and bonds are ultimately rational—based on investors making informed and savvy choices about what to do with their cash at any given moment of the day. The idea was that we all went into the investment markets with a fist full of cash and all the accurate information we’d need. Then, our conversations would go something like this: “Hmm, that stock is a bargain at this price: Buy! Those bonds aren’t yielding enough: Sell and redeploy our capital!” As the market moved to reflect the increasing demand on the savviest investments and the dearth of buyers for the less attractive investments, the prices would shift accordingly and investors would make new choices. Supply and demand are always in sync and investors are always rational.

The bulk of the world has now recognized this controversial theory to be largely irrelevant to individual investors.

It’s not that people never make rational decisions about their money. They do—just not all the time and not even when taken as a group. Wall Street’s favorite theory is now “behavioral finance.” This theory explains why smart people often make dumb decisions about their money.

The great thing about this shift is that behavioral finance is something we all can relate to. We know instinctively—or from personal experience—that ignorance, fear, or greed can get in the way of making smart choices. Instead of decisions, we make excuses. Instead of making money, we make . . . well, a mess.

This book is going to tell you how to invest wisely. Investing 101 is simple. It’s straightforward. You’ll get step-by-step instructions throughout. Anyone who reads and follows the directions will find investing easy to do. But if you let bad money habits overshadow your money smarts, your road to wealth will be long and bumpy.

How do you avoid that? Like anything else: You identify the problem and find a solution.

Here are some of the most common problems that face investors and simple ways to fix them. Many of these problems won’t relate to you, so skip them, unless you simply want to gloat.

Certain investment roadblocks are universal and can be relevant for any investor. Other problems are more likely to strike women than men, or men than women. The following sections look at all three types.

UNIVERSAL PROBLEMS

PROBLEM: Saving too little, or not at all.

“I would invest, but I just don’t have the money,” says the well-dressed twenty-five-year-old driving a BMW. “I’m going to start as soon as I get a raise.”

Okay. That was a slight exaggeration. And it would be easier to save if you earned more money, but sometimes life is just not fair.

Now, be fair with yourself and answer honestly: When was the last time you bought lunch or dinner at a restaurant instead of going for the cheaper alternative of packing a sack lunch or making your own dinner? When was the last time you bought a suit, a high-tech gadget, or a pair of shoes that you knew you didn’t need?

If you have a job that pays a decent wage—meaning anything that keeps you above subsistence level—you can afford to invest. Spend $2 less per day—the cost of one Starbucks coffee or one snack from the vending machines—and you’ve got $60 a month. That’s enough to plop into an automatic investment plan with a mutual fund.

Still think it’s a matter of poverty, not spending habits?

DID YOU KNOW?

Saving Habits and Salary Bumps

A number of studies have been done about whether individuals can afford to save, based on their income. They have found that aside from people at the polar ends of the income scale—the very rich and the very poor—the bulk of people in between think they could save, at least small amounts. Often, it’s a matter of whether they do, rather than whether they can. Increases in salary often lead to incremental increases in spending rather than increases in savings. This suggests that saving is a matter of habit, not income. If you aren’t saving now, you won’t start when you get a raise.

SOLUTION: You need a budget.

A budget doesn’t necessarily spell deprivation. In fact, a good budget is like a good diet. It feeds both your wants and needs in a healthy and sustainable way.

To put together a good budget—a real budget—you need to gather some records:

• Pull out your check register and bank statements.

• Collect your credit card bills.

• And find either your most recent tax return or your pay stubs.

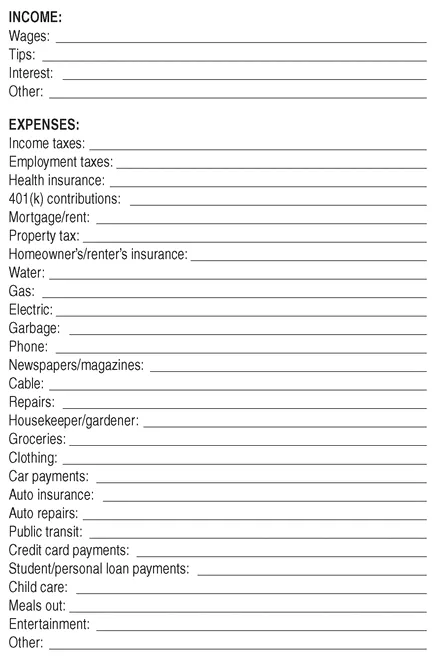

You’ll need these to remind yourself of your monthly, annual, and semiannual expenses—from rent or house payments to car insurance. The chart on the following pages will help you plot out what you’re shelling out each month.

You thought you were going to make up a projected budget? People who try to make up budgets without looking at their actual expenses are kidding themselves. The amount that you think you’re spending—or think you ought to be—is almost always less than what you actually spend. By writing down your actual purchases, you’re going to uncover your own personal money pits—places where you’re spending more money than you meant to. It might be dining out. It might be dry cleaning. It might be a shopping habit.

This isn’t about fitting your expenses into smaller boxes. This is about figuring out where your money is going and determining whether that’s where you want it to go. If it is, leave things alone. But if lots of little outlays are robbing you of long-term happiness by making it impossible to save for big goals—like a house or car or retirement—you might want to nip and tuck here or there. So, fill out the worksheet to find the flab in your financial life.

MONTHLY BUDGET

You’ve done the worksheets, but still can’t figure out where the money is going? You’re underestimating some expense because you’re paying more cash than attention. Do this: Start carrying a notebook around with you. Jot down every expense, from the $1 bagel to the $50 you spend filling up your car. Review your notebook after a month. Include the expenses in the budget and see if there’s something you can trim to add to savings. Realize that if you cut just $3.35 per day, you’ve found $100 a month to save. Voilà.

PROBLEM: Getting greedy.

You bought a stock figuring that it was going to go to $50. Then lo and behold, it popped up to $65. Based on all of your market knowledge, this is an incredibly high price for this stock. Its price/ earnings ratio (see Chapter 5) has never been this high, and you can’t imagine why it might be now. And yet, if it went to $65, it could go to $70, right? Maybe you ought to hang on just a little longer and see.

The fact is, the stock could go higher. Or it could go much, much lower. Consider 1999, when the prices of technology stocks had soared into the stratosphere and market pundits were contending that the sky was the limit. “It’s a new paradigm!” they shouted. It was hype. During the following three years, those stocks crashed and burned. A few have recovered. Many have not. People who were smart enough to sell when the prices were high made a killing. Those who got greedy got killed.

SOLUTION: Target price.

Every time you buy a stock, you should have a target—a price at which you would either sell the stock or reevaluate its prospects before you decide to leave it in your portfolio (see Chapter 6). Don’t let emotion—regardless of whether that emotion is fear, greed, or hope—rule your actions.

Evaluate all your stocks once a year. Make reasonable decisions about whether each one is a buy, a hold, or a sell. If you realize that you wouldn’t buy a stock today given its future prospects and that there are better opportunities out there, sell it. Live with the idea that you may never sell at the peak. That’s okay, as long as you also don’t sell at the nadir.

PROBLEM: Being tax-wise and bottom-line foolish.

I hear it all the time: “Never pay off your house. Your mortgage interest is tax deductible!” I’m always tempted to respond, “Okay, humor me for a minute here and let’s go through the math. If I pay $1 in mortgage interest, I’ll get to deduct it, which will save me, say, thirty cents on my federal income tax return. Aren’t I still out seventy cents?”

There are dozens of equally “tax-wise” investments being marketed in today’s world. My favorite is the variable tax-deferred annuity. What these say they do is allow you to save additional money for retirement in investments that mimic stock mutual funds.

The money you invest in this type of annuity isn’t tax deductible going in, but the investment gains are not taxed as returns and accumulate in the account. This allows you to trade all you want within the annuity and not immediately pay taxes on your gains. That’s the selling point that continues to push variable annuity sales ever higher. Roughly $90.6 billion in variable annuities were purchased during the first half of 2007. Total assets in these accounts were nearly 1.5 trillion, according to LIMRA International Inc., an insurance research and consulting firm.

Annuities are able to offer this benefit because they’re an insurance product. The insurance you get with an annuity generally is a guarantee that if the stock market crashes, which causes you to have a heart attack and die, your heirs are guaranteed to get at least as much as you originally invested in the annuity. That’s not much of a guarantee, but you pay for it dearly. The typical mortality and expense ratio on an annuity is around 1 percent. In other words, if the investments you hold within the annuity yield 10 percent, you’ll get 9 percent of that after the mortality expense is taken off the top. (To get a good read on the dollars-and-cents impact of that fee, read “The Real Cost of Fund Fees” in Chapter 8.)

But there’s a second cost too. Ironically, it’s a tax.

When you earn a profit on a long-term investment in a taxable account, you pay tax at preferential capital gains rates—usually 15 percent. However, money pulled out of a retirement account—and tax-deferred annuities fall into this category—is taxed at ordinary income tax rates, which can be as high as 35 percent. Even though you don’t have to pay taxes right away on money earned in an annuity, when you do pay, the tax rate is so much higher that it almost always overwhelms the short-term benefit of the annuity.

SOLUTION: Do the math.

Figure out whether the tax benefit of an investment is worth the cost. All too often, it’s not.

FOR WOMEN ESPECIALLY

By and large, women start investing later in life than men, set less money aside, and invest more conservatively. That has the unpleasant effect of leaving them poor in their old age. Some 80 percent of the elderly people living in poverty are women. So what’s their excuse?

PROBLEM: Emotional spending.

Do you shop when you have a fight with your boss or your spouse? Do you find that you “need” to hit the mall whenever you’re feeling down, as a way of boosting your spirits? Letting your psyche drive your spending is a common problem.

The bad news is your credit card balance is likely to rise faster than your spirits. As a result, you’re sentencing yourself to a life of servitude—working harder or more hours to pay your debts, which makes you all the more depressed.

If you need to get rid of your boss or your spouse, stop spending and start saving. Having money in the bank creates financial independence, which can lead to emotional and physical independence if you want it to. But how do you reverse the emotional drag that you’ve previously shopped away...