eBook - ePub

The Vertical Transportation Handbook

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Vertical Transportation Handbook

About this book

This new edition of a one-of-a-kind handbook provides an essential updating to keep the book current with technology and practice. New coverage of topics such as machine-room-less systems and current operation and control procedures, ensures that this revision maintains its standing as the premier general reference on vertical transportation. A team of new contributors has been assembled to shepherd the book into this new edition and provide the expertise to keep it up to date in future editions. A new copublishing partnership with Elevator World Magazine ensures that the quality of the revision is kept at the highest level, enabled by Elevator World's Editor, Bob Caporale, joining George Strakosch as co-editor.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Vertical Transportation Handbook by George R. Strakosch, Robert S. Caporale, George R. Strakosch,Robert S. Caporale in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Civil Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Essentials of Elevatoring

Early Beginnings

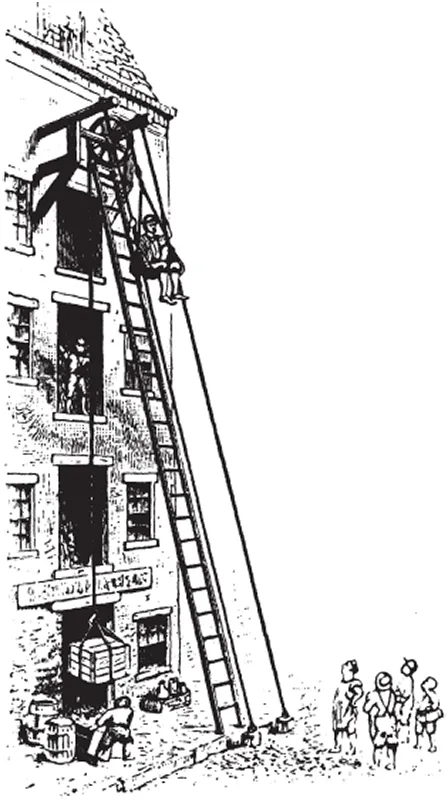

Since the time man has occupied more than one floor of a building, he has given consideration to some form of vertical movement. The earliest forms were, of course, ladders, stairways, animal-powered hoists, and manually driven windlasses. Ancient Roman ruins show signs of shaftways where some guided movable platform type of hoist was installed. Guides or vertical rails are a characteristic of every modern elevator. In Tibet, people are transported up mountains in baskets drawn by pulley and rope and driven by a windlass and manpower. An ingenious form of elevator, vintage about the eighteenth century, is shown in Figure 1.1 (note the guides for the one “manpower”). In the early part of the nineteenth century, steam-driven hoists made their appearance, primarily for the vertical transportation of material but occasionally for people. Results often were disastrous, because the rope was of fiber and there was no means to stop the conveyance if the rope broke.

Figure 1.1 A very early type of vertical transportation.

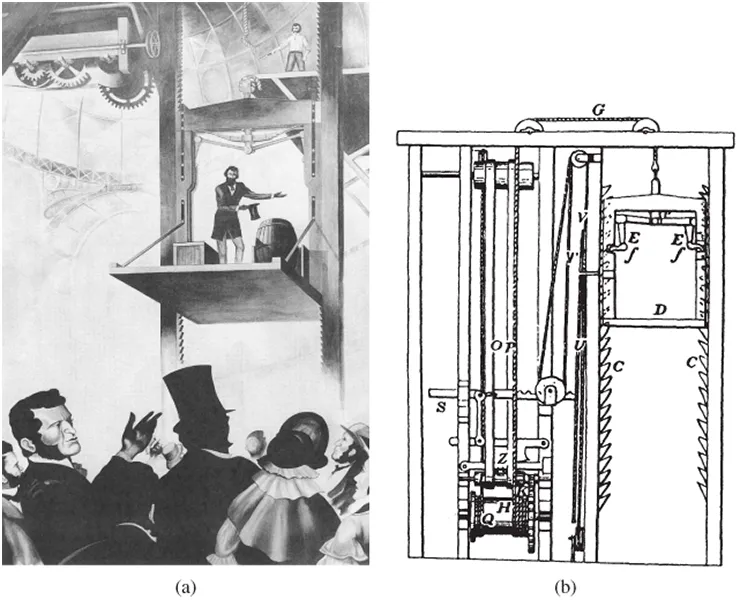

In the modern sense, an elevator1 is defined as a conveyance designed to lift people and/or material vertically. The conveyance should include a device to prevent it from falling in the event the lifting means or linkage fails. Elevators with such safety devices did not exist until 1853, when Elisha Graves Otis invented the elevator safety device. This device was designed to prevent the free fall of the lifting platform if the hoisting rope parted. Guided hoisting platforms were common at that time, and Otis equipped one with a safety device that operated by causing a pair of spring-loaded dogs to engage the cog design of the guide rails when the tension of the hoisting rope was released (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 (a) Otis's demonstration, Crystal Palace, New York, 1853. (b) Otis's patent sketch for a safety device (Courtesy Otis Elevator).

Elevator Safety Devices

Although Otis's invention of the safety device improved the safety of elevators, it was not until 1857 that public acceptance of the elevator began. In that year the first passenger elevator was installed in the store of E. V. Haughwout & Company in New York. This elevator traveled five floors at the then breathtaking speed of 40 fpm (0.20 mps).2 Public and architectural approval followed this introduction of the passenger elevator. Aiding the technical development of the elevator was the availability of improved wire rope and the rapid advances in steam motive power for hoisting. Spurring architectural development was an unprecedented demand for “downtown” space. The elevator, however, remained a slow vertical “cog” railway for quite a few years. The hydraulic elevator became the spur that made the upper floors of buildings more valuable through ease of access and egress. Taller buildings permitted the concentration of people of various disciplines in a single location and caused the cities to grow in their present form during the 1870s and 1880s.

Hydraulic Elevators

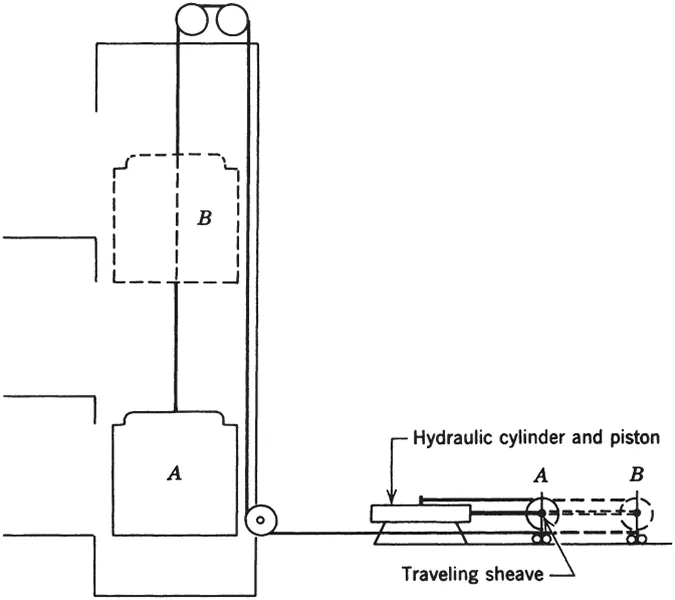

The hydraulic elevator provided a technological plateau for quite a few years; it was capable of higher rises and higher speeds than the steam-driven hoist-type elevator, limited by its winding drums (Figure 1.3). The hydraulic elevator also evolved from the direct ram-driven elevator to the so-called geared or roped hydraulic (Figure 1.4) capable of speeds of up to 700 fpm (3.5 mps) and rises of 30 or more stories. The cylinder and sheave arrangement was developed to use multiple sheaves and was mounted vertically for the higher rises. The 30-story building did not appear until after 1900, well after steel-frame construction was introduced, but the hydraulic elevator served practically all of the 10- to 12-story buildings of the 1880 to 1900 era.

Figure 1.3 Hydraulic elevator with handrope operation.

Figure 1.4 Roped hydraulic elevator.

It was in this era that many of the aspects of elevators as we know them today were introduced. Hoistways became completely enclosed, and doors were installed at landings. Before that time many hoistways were simply holes cut in the floor—occasionally protected by railings or grillage. Simple signaling was introduced, using bells and buzzers with annunciators to register a call, which was manually canceled. Groups of elevators were installed, the first recorded group of four elevators being in the Boreel Building in New York City, and the “majordomo” of “elevator buildings”—the starter—entered the scene and was assigned to direct the elevator operators to serve the riding public.

The first electric elevator quietly made its appearance in 1889 at the Demarest Building in New York City. This elevator was a modification of a steam-driven drum elevator, the electric motor simply replacing the steam engine. It continued in service until 1920 when the building was torn down. Electric power was here to stay, and the Otis Elevator Company installed the first automatic electric or push-button elevator in 1894.

With the tremendous building activity of the early 1900s and the increased size and height of buildings at that time, the questions of quantity, size, speed, and location of elevators began to arise. With these questions began the applied technology of elevatoring. A typical but wrong logic pattern of the time was: “Joe Doe has two elevators in his building and seems to be getting by all right. Since my building is twice as big, give me two twice the size.” It rapidly became evident that people in the latter building had to wait twice as long for service as those in Joe Doe's building, and complaints and building vacancies reflected their dissatisfaction. The example is typical, and soon elevatoring emerged as a special design discipline.

Elevatoring

Elevatoring is the technique of applying the available elevator technology to satisfy the traffic demands in multiple- and single-purpose multifloor buildings. It involves careful judgment in making assumptions as to the total population expected to occupy the upper floors and their traffic patterns, the appropriate calculation of the passenger elevator system performance, and a value judgment of the results so as to recommend the most cost-effective solution or solutions.

A major part of elevatoring is the understanding of pedestrian flow, pedestrian queuing, and the associated human engineering factors that will provide a nonirritating “lobby to lobby” experience. The traffic demands of passengers, service functions, and materials must be evaluated and all satisfied simultaneously for an optimal solution.

Elevatoring, in the modern sense, is the process of applying elevators and the building interfaces necessary for the vertical transportation of personnel and material within buildings. Service should be provided in the minimum practical time, and equipment should occupy a minimum of the building's space. The need for refinement in this process became apparent in the early 1900s as the height and cost of buildings increased.

Elevators changed radically in the early 1900s. As electricity became common, and with the introduction of the traction elevator, the water hydraulic was rapidly superseded. Helping its demise was the rapid rise of building heights—the Singer Building, 612 ft (185 m); the Metropolitan Life Tower, 700 ft (212 m); the Woolworth Building, 780 ft (236 m), all in New York City and built by 1912. The roped hydraulic could not be stretched to compete with such rises, and the direct-plunger-driven elevator required a hole as high as the rise. Telescoping rams were tried and proved unsatisfactory. These buildings were made possible by the introduction of the traction elevator into commercial use in 1903.

The history of the development of the mechanics of hoisting elevators is far beyond the scope of this volume and is detailed in at least two sources. One is the virtual Elevator Museum developed by William C. Sturgeon and Elevator World Magazine, which can be viewed online at www.theelevatormuseum.org, and the other is the volume A History of the Passenger Elevator in the 19th Century by Lee E. Gray, a professor of architectural history at the University of North Carolina. The latter also contains an overview of the development of elevatoring as discussed in this chapter.

Traction Elevators

Description

Up until about 1903, either drum-type elevator machines, wherein the rope was wound on a cylindrical drum, or the hydraulic-type elevator (the direct-plunger hydraulic or the roped hydraulic machine) was the principal means of hoisting force. Both had severe rise limitations: the drum type, in the size of the drum; and the hydraulic type, in the length of the cylinder. The drum-type elevator had the further disadvantage of requiring mechanical stopping devices to shut off power to prevent the car from being drawn into the overhead if the machine failed to stop by normal electrical means. On a hydraulic machine this is prevented by a stop ring on the plunger.

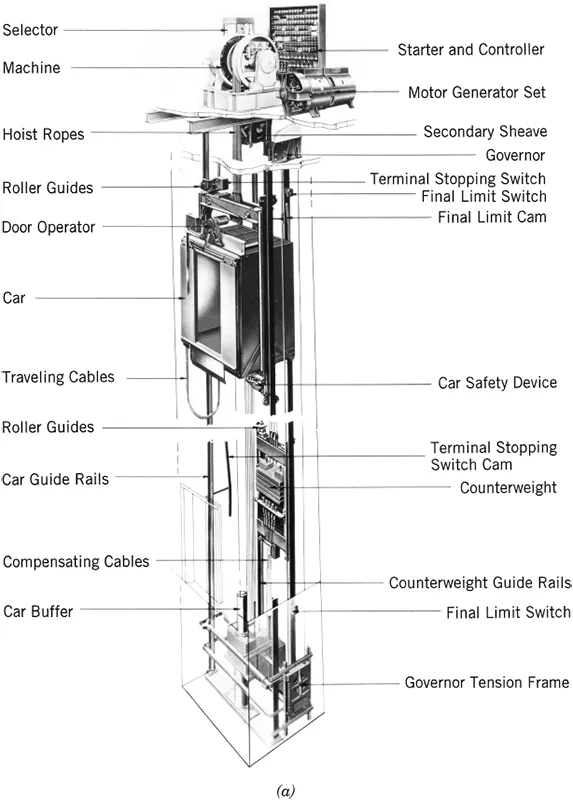

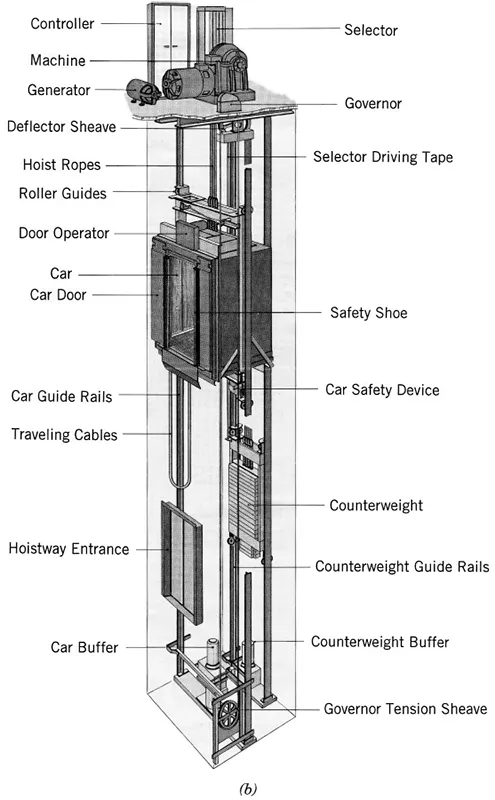

The traction machine had none of the rise disadvantage of either the hydraulic or drum machine. The traction principle is a means of transmitting lifting force to the hoist ropes of an elevator by friction between the grooves in the machine drive sheave and the hoist ropes (Figure 1.5a and b). The ropes are simply connected from the car to the counterweight and wrapped over the machine drive sheave in grooves. The weight of both the car and the counterweight ensures the seating of the ropes in the groove; for higher-speed elevators, the ropes are double-wrapped; that is, they pass over the sheave twice.

Figure 1.5 (a) Gearless elevator installation (Courtesy Otis Elevator). (b) Geared elevator installation (Courtesy Otis Elevator).

The safety advantages of the traction-type elevator are manifold: Multiple ropes are used, each capable of supporting the weight of the elevator, which increases the suspension safety factor as well as improving traction. The drive sheave is intended to lose traction if the car or counterweight bottoms on the buffers in the pit. However, this is not universal and depends on the proper condition of ropes, sheave, loading, and so on. The possibility of the car or counterweight being drawn into the overhead in the event of electrical stopping switch failure is reduced.

Traction elevators are capable of exceedingly high rises, the highest (or lowest) being in a mine application in South Africa for a depth of 2000 ft (600 m). The critical factors become the weight of the ropes themselves and the load imposed on the sheave shaft and its bearings. It was the traction elevator, in addition to other advances in building technology, that made today's tall buildings of 100 or more stories practical.

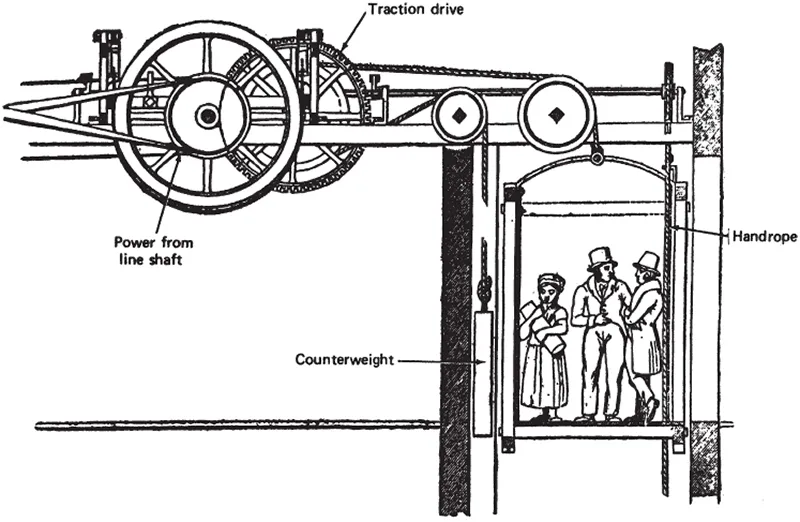

The traction principle has been available for centuries. The capstan on a ship is an example. The first known elevator application was the “Teagle” hoist, which was present in England about 1845, as shown in Figure 1.6. This old print shows the traction drive and the counterweight. Motive force was provided by means of belts to the line shafting in the building where the lift was installed. The operation was by handrope, as described for the hydraulic elevator shown in Figure 1.3. The handrope acted to engage the belt to the drive pulley, usually to the right or left of an idler pulley, to move the lift up or down.

Figure 1.6 Teagle elevator (circa 1845) (Courtesy Elevator World Magazine).

A development that has taken place in the past 10 years or so has been the location of a gearless-type machine in the hoistway either at the side or rear near the top. This results in the so-called “machine room–less” (MRL) elevator and is unique to various manufacturers. This machine has been redesigned into a “pancake” configuration, and the space over the hoistway is minimized. It has only been used in newer buildings, and the basic traction designs discussed in this chapter are still bei...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Contributors

- 1 The Essentials of Elevatoring

- 2 The Basis of Elevatoring a Building

- 3 Passenger Traffic Requirements

- 4 Incoming Traffic

- 5 Two-Way Traffic

- 6 Outgoing Traffic

- 7 Elevator Operation and Control

- 8 Space and Physical Requirements

- 9 Escalators and Moving Walks

- 10 Elevatoring Commercial Buildings

- 11 Elevatoring Residential Buildings

- 12 Elevatoring Institutional Buildings

- 13 Service and Freight Elevators

- 14 Nonconventional Elevators, Special Applications, and Environmental Considerations

- 15 Automated Materials-Handling Systems

- 16 Codes and Standards

- 17 Elevator Specifying and Contracting

- 18 Economics, Maintenance, and Modernization

- 19 Traffic Studies and Performance Evaluation Using Simulation

- 20 The Changing Modes of Horizontal and Vertical Transportation

- Appendix: Literature on Elevators and Escalators

- Index of Tables and Charts

- Index of Examples

- Subject Index