![]()

Part One

AWARENESS

![]()

Chapter 1

The Hurricane and the Earthquake

Warm waters stir the winds and fuel their fury. The storm groans, strengthens, and lumbers westward. Its path is true, though imprecise, and it lands where it will with all watching and waiting anxiously. Some may take shelter elsewhere. Others may risk it all by staying put.The storm may bring only rain and tempestuous gusts of wind. But it also could bring the beast, breaking even the most prepared.

Then we turn our eyes eastward and watch as the next one forms, builds, and heads right for us. But maybe it will hit someone else this time.

Tectonic plates strain in tension, ever struggling to move—even an inch. But they do move—relentlessly. On occasion they will make themselves known in the form of misaligned homes or growling tremblers. Yet we never see them coming in rage. In moments the plates yield, consuming everything in liquefied soil. The impact is overwhelming, but even when its anger subsides, the tension remains—straining until the next breakthrough. And we may never see it coming.

To many organizations, change comes like hurricane season. Everyone knows it’s coming. It’s the same every year. The only thing we don’t know is “Who will it hit this time?” Every storm that strikes does damage; but in most cases communities bounce back relatively quickly. Only in rare instances do we get a storm so powerful that when combined with certain other factors, it makes a permanent change in how a city or coastline appears.

With individual change initiatives, where we treat change as a discrete, manageable event, we get the same kind of result: It’s different for a little while, but we always try to go back to the way things were before (intentionally or unintentionally). Sticking with the status quo is human nature.Venturing out from business as usual is risky and uncomfortable.

To other organizations, change comes like the earthquake. We may never see it coming but have this nagging feeling that it is. The constant tension at the fault line gives us tremors every so often, hinting that there is more to come, so we prepare.

Some organizations opt to place themselves under intentional stress. In this environment, change is constant and often unmanageable, yet we are constantly aware of it. An example of intentional stress is where systems are designed to operate just-in-time to continuously meet changing customer demand. This enables us to learn and improve on a daily basis. We become learning organizations. Then, when the “Big One” comes, we have conditioned and equipped ourselves through growing our capacity to adapt.The disaster causes a disruptive breakthrough that permanently changes the way we do things, and we can never go back to the way things were before.

It feels odd using these natural disasters as metaphors for change, since we typically want things better after a change, and both hurricanes and earthquakes only seem to destroy. Is there a “better” approach to change? Do we want organizations to be stressed only during the change season, then relax for a few months before it starts again? Or would we rather have learning organizations that improve continuously, triggering on demand those innovative breakthroughs that permanently change the character and substance of the organization?

In 2005 we witnessed the “perfect storm” in New Orleans and its surrounding communities, with a combination of hurricane winds and levee failures. The devastation along the Gulf Coast of the United States was massive. It was also a year of tsunamis abroad and a huge earthquake in Pakistan. Many other natural and economic disasters have made their presence known in the intervening years. Our hearts certainly go out to the victims. We would honor them, and serve our organizations well by letting these disasters remind us of the ongoing lessons they teach us about our need to build the capacity to change, adapt, and learn.

![]()

Chapter 2

Importance of Mindset

Today the treacherous, unexplored areas of the world are not in continents or the seas; they are in the minds and hearts of men.

ALLEN E. CLAXTON, D.D., UNITED METHODIST MINISTER,

BROADWAY TEMPLE METHODIST CHURCH, NEW YORK, NY

The environment we live in is constantly in flux and unyielding in demanding change. As its demands for change accelerate, attempting to accomplish more with less continues to be the mantra of our times. Factor in the amount of data coming at each of us, and it’s little wonder that we adopt specific paradigms or ways of thinking and framing issues just to survive.The relentless pressure on cost has moved many jobs offshore, mandating development of new knowledge, skills, and abilities in order to fill the economic void. According to a study done by IBM, “By 2010, the amount of digital information will double every 11 hours.”1 In order to process and make decisions on this mountain of data, the human brain develops shortcuts, or specific templates for thinking, evaluating, and getting to a quick decision. Some of these mindsets serve us well. Some do not. This section summarizes a key construct in the Change Challenge Framework that follows in Chapter 3, called mindset.

Definition

Webster’s Dictionary defines mindset as “a mental inclination, tendency, or habit.”2 This concept is fundamental to building individual and organizational readiness for change. Enrolling the organization in continuously improving its response to environmental challenges is about winning the hearts and minds of its employees. Having the greatest technology, products, executive team, and organizational structure is no guarantee of success unless individual and organizational mindsets are synchronized with them for optimal performance.

Core Elements

Carol Dweck is a former professor of Psychology at Columbia University, and is currently at Stanford University. She is one of the leading researchers in the fields of personality, social psychology, and developmental psychology. Dr. Dweck’s research has concluded that the worldview a person adopts will profoundly affect the way they lead their life. She describes two specific types of mindset that are fundamental to our understanding the different ways people approach change: the fixed mindset and the growth and development mindset.3

People with fixed mindsets believe their capabilities are carved in stone. In this belief system, individuals are endowed with a certain amount of intelligence, personality, and moral character. Our education system reinforces this mindset through standard testing and IQ measurement, for example. As an illustration, Dweck describes her sixth-grade teacher, who was of this mindset because “she believed that people’s IQ scores told the whole story of who they were.”4

Individuals with this worldview interpret most situations with an “either/or” decision process: succeed or fail, win or lose. Risks are to be mitigated and avoided. People with this mindset have a great deal of passion for the status quo and are generally resistant to change. If a need for change surfaces, such people are likely to perceive it as a change event, after which a return to business as usual is customary.

People with the growth and development mindset believe that their qualities can be cultivated and expanded through their personal efforts. They believe that anyone can change and grow through application and experience. These types of people feel that their actual potential is infinite, and it can be developed with impassioned effort and continuous learning. Individuals of this mindset are more inclined to view the world through a lens of win/win or “both/and” decisions. Challenges are actively pursued as opportunities, and risk is measured to a predefined level of tolerance.

Thus, the individual or organization with the fixed mindset is likely to interpret change as a threat and resist it. However, the individual or organization with a growth and development mindset may choose to view change as an opportunity to upgrade skills and capacity to change. In today’s world of constant, turbulent change, sticking with the status quo can be deadly, and individuals should take advantage of every opportunity to increase their knowledge and capabilities.

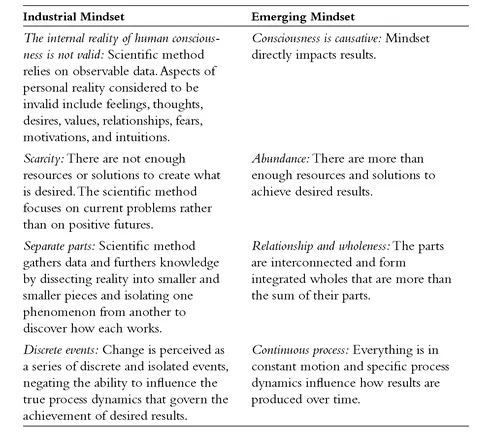

Dean Anderson and Linda Ackerman Anderson discuss two types of mindset that are prevalent in the world today in their book Beyond Change Management.5 Clearly, the industrial mindset made significant contributions in fueling the Industrial Revolution, mass production efficiencies, and the scientific management techniques that provided affordable products for consumers on a mass scale. “This mindset has been both a blessing and a curse,” say the authors, first, because of the benefits to society, and second, because of the effects such as “pollution and destruction of the ecosystem, overpopulation, weapons of mass destruction, and alienation of people.” They advocate the emerging mindset, stemming from books such as Leadership and the New Science by Margaret Wheatley.6

Exhibit 2.1 lists some characteristics of each of the two mindsets. Although the mindsets are different from and opposite of each other, the Andersons suggest that we not view them from an either/or perspective. “The emerging mindset does not negate or replace the industrial mindset, but rather transcends and includes it.” The authors of this book believe that the industrial mindset has been applied too broadly and that the change-ready organization must extract the wisdom from each mindset in order to build an effective change strategy.

Exhibit 2.1 Industrial versus Emerging Mindset

SOURCE: Adapted from Dean Anderson and Linda S. Ackerman Anderson, Beyond Change Management: Advanced Strategies for Today’s Transformational Leaders (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer, 2001), 112-117.

Impact

Now that we understand the types of mindset, let’s focus on how this concept manifests itself in an organizational context. How individuals and the collective organizations they comprise interpret change will have a direct relationship to the success and sustainment of a change initiative. In addition to the tangible aspects of change that typically are addressed, such as technology, systems, and organizational structure, two additional aspects of change must also be addressed as part of an overall plan. We recommend inclusion of these two areas relating to mindset, to address the hearts and minds at the individual level, and as collectively represented in the organizational culture.These are:

• Organizational mindset. This is often referred to as the organizational culture. It consists of the formal and informal processes, policies, group mental models, traditions, and norms of behavior that drive how the organization responds to the challenges of its environment in pursuit of its mission.

• Personal mindset. This mindset is comprised of individual values, behaviors, preferences, habits, and attitudes. Ignorance of the importance of this mindset can be disastrous, because individuals can either be ...