- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Bullying at School is the definitive book on bullying/victim problems in school and on effective ways of counteracting and preventing such problems.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bullying at School by Dan Olweus in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

What We Know About Bullying

What We Know About Bullying

Stories from the Press (somewhat modified)

For two years, Johnny, a quiet 13-year-old, was a human plaything for some of his classmates. The teenagers badgered Johnny for money, forced him to swallow weeds and drink milk mixed with detergent, beat him up in the rest room and tied a string around his neck, leading him around as a “pet.” When Johnny’s torturers were interrogated about the bullying, they said they pursued their victim because “it was fun.”

In Weston-super-Mare, Avon, Sarah, aged 10, was regularly taunted by two unruly girls because she wouldn’t join them in disrupting lessons. They called her names, threatened her with their fists, and persuaded others to make sure she was excluded by the rest of the class. “I used to love school,” says a bewildered Sarah, “but now I hate it.”

Linda, aged 12, was allegedly victimized by her classmates because she was “too posh.” It appears that Linda had made friends with another girl in the class and they went around together. The alleged ringleader of the small bully group tried to destroy this friendship and eventually succeeded, leaving Linda fairly isolated. Later on, another girl in the bully group persuaded Linda to give a party at home, then made sure no one came. Linda’s self-confidence was completely destroyed.

Schoolboy Philip C. was driven to his death by playground bullying. He hanged himself after being constantly threatened, pushed around and humiliated by three of his classmates. Finally, when the shy 16-year-old’s examination notes were stolen days before he was due to sit an important exam, he could take no more. Frightened to tell his parents, Philip chose to die. When he came home from school, he hanged himself by a rope from his bedroom door.

What is Meant by Bullying?

The word used in Scandinavia for bullying or bully/victim problems is “mobbing” (Norway, Denmark) or “mobbning” (Sweden, Finland). This word has been used with several different meanings and connotations. The original English word stem “mob” implies that it is a usually large and anonymous group of people which is engaged in the harassment (Heinemann 1972; Olweus 1973a). But the term has also often been used when one person picks on, harasses, or pesters another. Even if this usage is not quite adequate from a linguistic point of view, I believe it is important to include in the concept of “mobbing” or bullying both the situation in which a single individual harasses another and that in which a group is responsible for the harassment. Recent data collected in my Bergen study showed that a substantial portion (some 35–40 percent) of victimized students were bullied primarily by a single student. Accordingly, it is natural to regard bullying from a single student and from a group as closely related phenomena – even if there may be some differences between them. In particular, it is reasonable to expect that bullying by several peers is more unpleasant and possibly more detrimental to the victim.

I define bullying or victimization in the following general way: A student is being bullied or victimized when he or she is exposed, repeatedly and over time, to negative actions on the part of one or more other students (Olweus 1986 and 1991).

The meaning of the expression “negative actions” must be specified further. It is a negative action when someone intentionally inflicts, or attempts to inflict, injury or discomfort upon another – basically what is implied in the definition of aggressive behavior (Olweus 1973b). Negative actions can be carried out by words (verbally), for instance, by threatening, taunting, teasing, and calling names. It is a negative action when somebody hits, pushes, kicks, pinches, or restrains another – by physical contact. It is also possible to carry out negative actions without use of words or physical contact, such as by making faces or dirty gestures, intentionally excluding someone from a group, or refusing to comply with another person’s wishes.

Even if a single instance of more serious harassment can be regarded as bullying under certain circumstances, the definition given above emphasizes negative actions that are carried out “repeatedly and over time.” The intent is to exclude occasional nonserious negative actions that are directed against one student at one time and against another on a different occasion.

Bullying can be carried out by a single individual – the bully – or by a group. The target of bullying can also be a single individual – the victim – or a group. In the context of school bullying, the target has usually been a single student. Data from my Bergen study indicate that, in the majority of cases, the victim is harassed by a group of two or three students.

It must be stressed that the term bullying is not (or should not be) used when two students of approximately the same strength (physical or psychological) are fighting or quarreling. In order to use the term bullying, there should be an imbalance in strength (an asymmetric power relationship): The student who is exposed to the negative actions has difficulty defending him/herself and is somewhat helpless against the student or students who harass.

It is useful to distinguish between direct bullying – with relatively open attacks on a victim – and indirect bullying in the form of social isolation and intentional exclusion from a group. It is important to pay attention also to the second, less visible form of bullying.

In the present book the expressions bullying, victimization, and bully/victim problems are used with approximately the same meaning.

See also under the headings Portrait Sketches of Henry and Roger, a Victim and a Bully (p.49) and Guide for the Identification of Possible Victims and Bullies (p. 53) for examples and characteristics of bully/victim problems.

Some Information About the Recent Studies

The basic method of data collection in the recent large-scale studies in Norway (and Sweden, below), has been a Bully/Victim Questionnaire that I developed in connection with the nationwide campaign against bullying. (There are English versions of the questionnaire – one for grades 1–4, and another for grades 5–9 and higher grades. For information about the questionnaire, please write to the author, University of Bergen, Oysteinsgate 3, N-5007 Bergen, Norway.) The questionnaire, which is filled out anonymously by the students and can be administered by teachers, differs from previous questionnaires on bully/victim problems in a number of respects, including the following:

- it provides a “definition” of bullying so as to give the students a clear understanding of what they are to respond to

- it refers to a specific time period (a “reference period”)

- several of the response alternatives are fairly specific, such as “about once a week,” and “several times a week,” in contrast to alternatives like “often” and “very often” which lend themselves to more subjective interpretation

- it includes questions about the others’ reactions to bullying, as perceived by the respondents, that is, the reactions and attitudes of peers, teachers, and parents

In connection with the nationwide campaign all primary and secondary/junior high schools in Norway were invited to take the questionnaire. We estimate that approximately 85 percent actually participated. For closer analyses, I selected representative samples of some 830 schools and obtained valid data from 715 of them, comprising approximately 130,000 students from all over Norway. These samples constitute almost a fourth of the whole student population in the relevant age range (roughly ages 8 to 16; first-grade students did not participate, as they did not have sufficient reading and writing ability to answer the questionnaire). This set of data gives good estimates of the frequency of bully/victim problems in different school forms, in different grades, in boys as compared with girls, etc.

In the same academic year, I also conducted a parallel study using the same questionnaire with 17,000 students in grades 3 through 9 in three cities in Sweden (Göteborg, Malmö, and Västerås with populations varying from 420,000 to 120,000 inhabitants). This study was designed to permit comparison with the data collected from three Norwegian cities of approximately the same size (the three largest cities in Norway: Oslo, Bergen, and Trondheim).

To gain more detailed information on some of the mechanisms involved in bully/victim problems and on the possible effects of the intervention program I also conducted a special project in Bergen. This study (here called the Bergen study) comprised some 2,500 boys and girls in four consecutive grades, originally 4 through 7 (varying in age from 10 to 15 years), from 28 primary and 14 junior high schools. In addition, we obtained data from 300–400 teachers and principals as well as some 1,000 parents. We collected data from these subjects at several points in time over a period of two and a half years.

One Student out of Seven

On the basis of the nationwide survey, one can estimate that some 84,000 students, or 15 percent of the total in the Norwegian primary and junior high schools (568,000 students in 1983–4), were involved in bully/victim problems “now and then” or more frequently (fall 1983) – as bullies or victims. This percentage represents one student out of seven. Approximately 9 percent, or 52,000 students, were victims, and 41,000, or 7 percent, bullied other students with some regularity. Some 9,000 students were both victim and bully (1.6 percent of the total of 568,000 students or 17 percent of the victims).

In calculating the percentages above, I have drawn the line at “now and then:” For a student to be considered bullied or bullying others, he or she must have responded that it happened “now and then” or more frequently.

Analyses from the Bergen study indicate that there are good grounds for placing a cutting point just here. But it can also be useful to estimate the number of students who are involved in more serious bully/victim problems. We find then that slightly more than 3 percent, or 18,000 students, in Norway were bullied “about once a week” or more frequently, and somewhat less than 2 percent, or 10,000 students, bullied others at that rate. Using this cutting point, only 1,000 students were both bully and victim (0.2 percent of the total or 6 percent of the victims). A total of approximately 27,000 students (5 percent) in Norwegian primary and secondary/junior high schools were thus involved in more serious bullying problems as victims or bullies – about one student out of 20.

Analyses of parallel teacher nominations in approximately 90 classes (Olweus 1985) suggest that the reported results do not give an exaggerated picture of the frequency of bully/victim problems. Considering that the student (as well as the teacher) questionnaire refers to only a part of the autumn term, it is obvious that the figures in fact underestimate the number of students who are involved in such problems during a whole year.

Against this background, it can be stated that bullying is a considerable problem in Norwegian schools, a problem that affects a very large number of students.

Data from other countries such as Sweden (Olweus 1986), Finland (Lagerspetz et al. 1982), England (Smith 1991; Whitney & Smith 1993), USA (Perry et al. 1988), Canada (Ziegler & Rosenstein-Manner 1991), The Netherlands (Haeselager & van Lieshout 1992), Japan (Hirano 1992), Ireland (O’Moore & Brendan 1989), Spain (Ruiz 1992), and Australia (Rigby & Slee 1991), indicate that this problem also exists outside Norway and with similar and even higher prevalence rates.

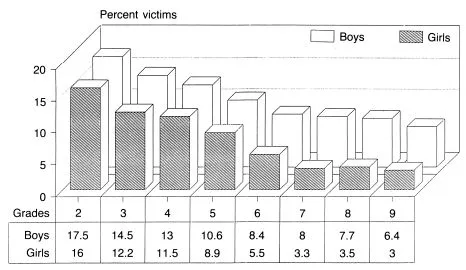

Bully/Victim Problems in Different Grades

If one draws a graph of the percentage of students in different grades who are bullied at school, a fairly smoothly declining curve is obtained for both boys and girls (see figure 1). The decline is most marked in the primary school grades (1 through 6, roughly corresponding to ages 7 through 13 in Scandinavia). Thus the percentage of students who are bullied decreases with higher grades. It is the younger and weaker students who reported being most exposed.

In secondary/junior high school (grades 7–9, roughly corresponding to ages 13 through 16) the curves decline less steeply. The average percentage of students (boys and girls combined) who were bullied in grades 2–6 (11.6 percent) was approximately twice as high as that in grades 7–9 (5.4 percent). With regard to the ways in which the bullying is carried out, there is a clear trend toward less use of physical means (physical violence) in the higher grades.

From the Bergen study it can also be reported that a considerable part of the bullying was carried out by older students. This was particularly marked in the lower grades: more than 50 percent of the bullied children in the lowest grades (2 and 3) reported that they were bullied by older students.

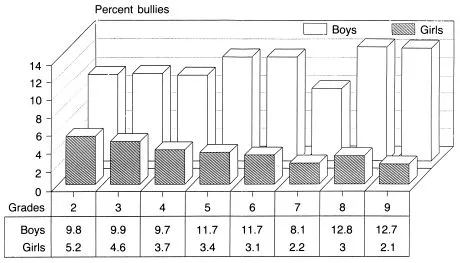

As regards the tendency to bully other students, depicted in figure 2, the changes with grades are not as clear and systematic as in figure 1. The average percentage for the secondary/junior high school boys was slightly higher (11.3 percent) than for the boys in the lower grades (10.7 percent), whereas the opposite was true for the girls (2.5 percent in junior high vs. 4.0 percent in the lower grades). The relatively marked drop in the curves for grade 7, in particular for the boys, is probably a reflection of the fact that these students were the youngest ones in secondary/junior high school and accordingly did not have “access to suitable victims” in lower grades to the same extent.

Figure 1 Percentage of students in different grades who reported being bullied. The figures are based on a total of 42,390 boys and 40,940 girls.

The trends demonstrated in the Norwegian data were confirmed in all essentials in the corresponding analyses with Swedish students (Olweus 1986) and with English students from the Sheffield area (though the levels of problems were somewhat higher for these students) (see Whitney & Smith 1993).

The most remarkable result from the preceding analyses is that bully/victim problems in primary schools were considerably more marked than previously assumed.

Figure 2 Percentage of students in different grades who reported having bullied other students. The figures are based on a total of 42,324 boys and 40,887 girls.

Have Bully/Victim Problems Increased?

Several different methods, including questionnaires (for brief overviews in Scandinavian languages, see Raundalen & Raundalen 1979; Pikas 1975), teacher nominations (Olweus 1973a and 1978), and peer ratings (Lagerspetz et al. 1982; Olweus 1978) have been used in previous Scandinavian studies of the frequency of bully/victim problems. The samples have consisted mainly of students in grades 6 through 9. In summary, it can be stated that the percentages of bullied and bullying students, respectively, were found to be in the vicinity of 5–10 percent.

By and large, the figures in these studies conducted chiefly in the 1970s are somewhat lower than the percentages obtained in the surveys reported on above. It should be noted, however, that many of these earlier studies are very preliminary in nature, with small sample sizes and no clear definition of what is meant by bullying (and with nonspecific response alternatives, see above). In addition, the studies were often conducted by undergraduate students with little supervision from more experienced researchers. Against this background, it is difficult to ascertain whether the noted discrepancy actually indicates an increased frequency of bully/victim problems in recent years, or whether it reflects methodological differences. There are simply no good data available to assess directly whether bully/victim problems have become more or less frequent in the 1980s and early 1990s. Several indirect signs suggest, however, that bullying both takes more serious forms and is more prevalent nowadays than 10–15 years ago.

Whatever method of measurement used, there is little doubt that bullying is a considerable problem in the primary and secondary/junior high schools of Norway (and other countries), and one which must be taken seriously. At the same time, it is important to recognize that 60–70 percent of the students (in a given semester) are not involved in bullying at all, neither as targets nor as perpetrators. It is essential to make use of this group of students in efforts to counteract bully/victim problems at school (see Part II).

Bullying Among Boys and Girls

As is evident from figure 1, there is a trend for boys to be more exposed to bullying than girls. This tendency is particularly marked in the secondary/junior high school grades.

These results concern what was called direct bullying, with relatively open attacks on the victim. It is natural to ask whether girls were more often exposed to indirect bullying in the form of social isolation and intentional exclusion from the peer group. One of the questions in the questionnaire makes it possible to examine this issue (“How often does it happen that other students don’t want to spend recess with you and you end up being alone?”).

The responses confirm that girls were more exposed to indirect and more subtle forms of bullying than to bullying with open attacks. At the same time, however, the percentage of boys who were bullied in this indirect way was approximately the same as that for girls. In addition, a somewhat larger percentage of boys was exposed to direct bullying, as mentioned above. (It may also be of interest to note that there was a fairly strong association between being a victim of direct and of indirect bullying.)

It should be emphasized that these results reflect main trends. There are of course a number of schools and classes in which there are more girls, or as many girls as boys, who are exposed to direct bullying, also in junior high school.

An additional result from the Bergen study is relevant in this context. Here it was found that boys carried out a large part of the bullying to which girls were subjected. More than 60 percent of bullied girls (in grades 5–7) reported being bullied mainly by boys. An additional 15–20 percent said they were bullied by both boys and girls. The great majority of boys, on the other hand – more than 80 percent – were bullied chiefly by boys.

These results direct our attention to figure 2, which shows the percentage of students who had taken part in bullying other students. It is evident here that a considerably larger percentage of boys than girls had participated in bullying. In secondary/junior high school, more than four times as many boys as girls reported having bullied other students.

It should also be reported that bullying with physical means is more common among boys. In contrast, girls often use more subtle and indirect ways of harassment such as slandering, spreading of rumors, and manipulation of friendship relationships (e.g., depriving a girl of her “best friend”). Nonetheless, harassment with non-physical means (words, gestures, etc.) is the most common form of bullying also among boys.

In summary, boys were more often victims and in particular perpetrators of direct bullying. This conclusion is in good agreement with what can be expected from research on sex differences in aggressive behavior (Maccoby & Jacklin 1974 and 1980; Ekblad & Olweus 1986). It is well-documented that relations among boys are by and large harder, tougher, and more aggressive than a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Understanding Children’s Worlds

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: What We Know About Bullying

- Part II: What We Can Do About Bullying

- Part III: Effects of the Intervention Program

- Part IV: Additional Practical Advice and a Core Program

- References

- Index