![]()

Section 1

Basics of Cardiac Anatomy and Electrophysiology

![]()

1.1

Cardiac Anatomy, Physiology, Electrophysiology, and Pharmacology

Linda K. Ottoboni, Aimee Lee, and Paul Zei

Electrical stimulation is the key in initiating the sequence of events that result in cardiac contraction, the ultimate measure of cardiac performance. The inherent pacing properties that are required to generate an electrical impulse, the intrinsic conduction pathways that move depolarization from the initial impulse throughout the entire cardiac muscle, and finally, the patterns of depolarization that create an optimal squeeze of the cardiac muscle are the result of the electrical conduction system and mechanical system functioning synchronously. Impulse generation and dispersion to all areas of the heart muscle via cell-to-cell activation and via electrical pathways must be well understood to comprehend the complexity of electrical conduction and the strategies for treating conduction abnormalities. This chapter will provide an overview of cellular physiology, electrical physiology, the anatomy of the conduction system, and the medications that can be used to treat conduction abnormalities. A thorough understanding of the normal anatomy and physiology of the conduction system will enable the allied professional to understand the rationale for utilizing specific arrhythmia treatment modalities, whether it be medications, ablations, or devices.

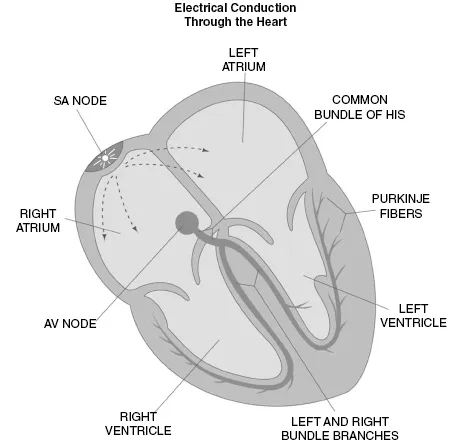

ANATOMY OF THE CARDIAC CONDUCTION SYSTEM

The anatomy of the conduction system is composed of electrical tracts within the myocardium. This electrical network is strategically arranged in the nodes, bundles, bundle branches, and branching networks of fascicles. The cells that form these structures lack contractile capability but can generate spontaneous electrical impulses and alter the speed of electrical conduction throughout the heart. The sinoatrial (SA) node, internodal tracts, atrioventricular (AV) node, bundle of His, right bundle, left bundle, anterior and posterior fascicles, and the Purkinje fibers are all the necessary conduction routes established throughout the cardiac muscle (Fig. 1.1.1). Normal conduction utilizes this electrical conduction system to expedite transmission of the electrical impulse from the top of the heart to the bottom. Abnormal conduction or arrhythmias are the result of an arrhythmogenic site or region that interferes, alters, or bypasses the normal conduction circuit. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of normal conduction provides a foundation for better understanding the mechanisms present in abnormal conduction or arrhythmias.

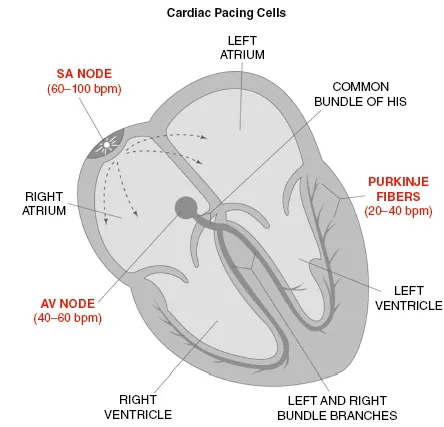

Anatomically, the SA node is subepicardially located in the left upper corner of the right atrium, near its junction with the superior vena cava. The SA node is the native pacemaker site within the heart and is composed of cells capable of impulse formation or “pacing.” Pacing cells within the SA node independently move to a threshold potential, thereby initiating depolarization. The SA node establishes the intrinsic heart rhythm between 60–100 pulses per minute but is influenced by the autonomic nervous system to meet the changing requirements of the body (Fig. 1.1.2). The region of the sinus node has numerous nerve endings and is predominantly regulated by the parasympathetic system or acetylcholine at rest and the sympathetic tone is mediated with the release of norephinephrine to meet increased energy requirements.

The sinus node lies near the central artery whereby it obtains its blood supply from the right coronary artery 55–65% of the time, while in 35–45% the left circumflex provides blood flow (Anderson et al. 1979). The function of the sinus node may be jeopardized if the blood supply is reduced due to coronary artery disease or an increase in fibrous tissue with maturity, resulting in fewer SA cells available for impulse formation within the sinus node (Davies and Pomerance 1972).

Once the impulse is initiated within the SA node, it not only travels cell to cell through the atrium but also utilizes more specialized, expedient pathways known as internodal tracts (Fig. 1.1.1). The Bachmann’s bundle moves away from the SA node anteriorly around the superior vena cava and then bifurcates with one branch leading from the right to the left atrium, while the other branch descends along the interatrial septum into the anterior portion of the AV node (fast pathway). The Wenckebach’s tract transfers the stimulus from the superior region of the SA node, posterior to the superior vena cava, and travels through the atrial septum to the AV node, while the third pathway (Thorel’s) is responsible for moving the impulse inferiorly and posteriorly along the coronary sinus, arriving into the posterior portion of the AV node (slow pathway).

Once atrial depolarization is completed, depolarization moves into the AV node via the internodal tracts previously described or via cell-to-cell conduction. Normally, the structure of the AV node is the only conduction route from the atrium to the ventricle because the chambers are separated by fibrous and fatty tissue that is nonconductive. The primary function of the AV node is to slow electrical conduction adequately to synchronize atrial contribution to ventricular systole. The AV node is also capable of rescue pacing when the SA node fails and will provide a heart rate of 40–60 bpm (Fig. 1.1.2). By contrast, an ectopic site within the AV node is capable of pacing competitively against the SA node to produce arrhythmias or junctional tachycardias greater than 100 bpm.

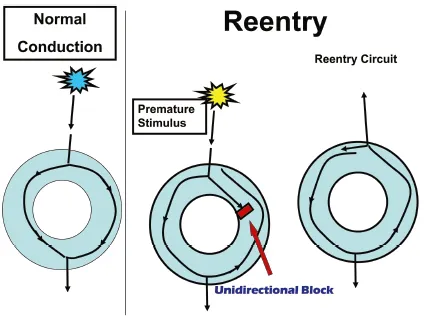

The fast and slow pathways of the AV node are anatomical as well as functional structures. Slow pathway physiology is not seen in every individual. The fast pathway conducts more quickly but has a longer refractory period or recovery period. By contrast, the slow pathway conducts more slowly but has a shorter refractory or recovery period. Conducted impulses commonly travel along the fast pathway through the AV node, but with increased heart rates or the presence of a premature stimulus, the fast pathway may be unable to transmit because it is unable to recover fast enough to transmit the stimulus or be “refractory.” Because the slow pathway has a shorter effective recovery time or is able to recover more quickly, it is able to transmit a signal down the slow pathway while the fast pathway is still recovering. The timing of recovery and the ability or inability to transmit a signal can result in a reentrant tachycardia (Fig. 1.1.3). Reentry is the result of a circuit that is initiated by a signal, often early, being blocked and forced to move in the opposite direction. When the electrical signal conducts back toward the area of block, the structure has had time to recover and is now able to transmit the signal in the opposing direction. Hence, the critical timing sequence of the signal being transmitted creates an independent reentrant circuit.

Once the activation through the AV node occurs, depolarization travels to the common bundle of His (also called His bundle or common bundle). The region where the AV node (node of Tawara) and the His bundle join can be termed the triangle of Koch. Anatomically, the triangle of Koch includes the coronary ostium, the tendon of Todaro, and the tricuspid valve annulus along the septal leaflet. The AV node is approximately 5–6 mm long and 2–3 mm wide, and 0.5–1.0 mm thick, although there is some discrepancy in what is included in the AV node (Hecht et al. 1973; Becker and Anderson 1976). The blood supply of the AV node is the AV nodal artery and is usually dual supplied by the right coronary artery in 90% of the patients and the remaining 10% receive blood from the left circumflex coronary artery. Similar to the SA node, there is evidence of a generous autonomic innervation of the AV node, and therefore, the autonomic nervous system influences the rate of conduction through the AV node. AV nodal conduction abnormalities arise from altered blood supply, change in autonomic tone, increased fibrous tissue replacing AV nodal tissue, and an alteration in the normal conduction route.

Once depolarization moves through the bundle of His, it branches out to the right and left bundle branches. The right bundle branch remains compact until it reaches the right distal septal surface, where it branches into the interventricular septum and proceeds toward the free wall of the right ventricle. Because the left ventricle is larger in size, the left bundle branch moves conduction down the left septum and then bifurcates into a posterior and anterior descending fascicle. The left fascicles extend to the base of the papillary muscles and the adjacent myocardium, while the right bundle stays along the interventricular septum superficially within the endocardium (see Fig. 1.1.1).

The final destination is the arrival into the complex network of the specialized Purkinje fibers, capable of independently pacing at a rate of 20–40 bpm if needed along with rapid conduction (Fig. 1.1.2). Once the impulses arrive at the Purkinje fibers, they proceed slowly from the endocardium to epicardium throughout the left and right ventricles. This assures earlier activation at the apex of the heart, the sequence necessary to achieve the most efficient cardiac pumping, which is the intended outcome of cardiac depolarization.

CARDIAC ACTION POTENTIAL

The conduction system is composed of two distinctly different cells, pacing cells and nonpacing cells. “Pacing” cells are specialized cells with automaticity, meaning that they can move to a threshold potential independently and propagate or spontaneously initiate an impulse. The specialized cells with automaticity reside within the SA node, AV node, and the Purkinje fibers. All the rest of the cardiac cells, myocytes, are “nonpacing cells” or conducting cells, which means they can be stimulated by an electrical impulse arriving at the cell and then conduct or transmit the impulse from one cell to another cell once the cell is stimulated. Therefore, cardiac cells are unable to initiate an impulse contrary to pacing cells.

Cells have the property of pacing or conductivity due to the electrical charge or voltage on the inside of the cell compared with the voltage on the outside of the cell. If the electrical charge inside the cell is less than the charge on the outside, the transmembrane potential is “negative.” By contrast, if the electrical charge is greater inside the cell than outside the cell, the transmembrane potential is “positive.” Depolarization occurs when the transmembrane potential is positive, while repolarization restores the cell to its negative state, making it available to accept an electrical stimulus in its negative or resting state. Pacing cells are able to depolarize independently, in contrast to a nonpacing cell, which is dependent on an outside stimulus to initiate depolarization.

The transmembrane potential is altered by ions moving in and out of the cell across the cellular membrane. Ion movement is the result of the selective permeability of ion channels distributed along the cell membrane. The movement of the Na+, K+, and Ca2+ ions are the most predominant throughout the cardiac action potential. These ions move in or out of the cell as a result of a change in concentration gradient, electrical gradient, ion pumps, and altered membrane permeabilities (Table 1.1.1). Alterations in permeability to specific ions are most often regulated by voltage-gated channels that will open or close depending on the current measured between the inside and the outside of the cell, but there are additional properties that are responsible for moving ions in and out of the cell (Table 1.1.2). Some of these ion shifts occur passively, while other transport mechanisms require energy at the cellular level. The ion “pumps” or ion transfers that require energy will be at risk in the event that the cell does not have an energy source or is oxygen deprived, for example, ischemia provides an opportunity for arrhythmias to occur.

Phases of the Cardiac Action Potential

The cardiac action potential of the “nonpacing” cell consists of five phases:

- Phase 0—rapid depolarization

- Phase 1—early rapid repolarization

- Phase 2—plateau phase

- Phase 3—repolarization

- Phase 4—resting phase

The cell moves from one phase to another very quickly with the entire process occurring within milliseconds. Although we describe each specific phase, the transition from one phase to another is dynamic and seamless. The action potential takes a round-trip journey in that the signal is able arrives at baseline (phase 4) and is able to travel to the destination (depolarization — phase 0). Then, the action potential is able to return back to home (repolarization—phases 1–4) and prepare to depart from home or baseline (resting—phase 4) once again. What actually occurs at each phase is described below.

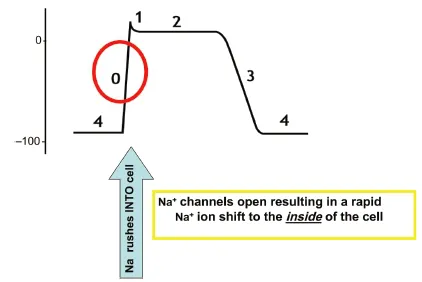

Phase 0—Rapid Depolarization

When an electrical impulse arrives at the cell, the membrane potential shifts from approximately −90 to −60v and reaches “threshold” potential. The shift in voltage triggers the “voltage-gated” sodium channels to open and the permeability of the plasma membrane to sodium ions (PNa+) increases, thereby resulting in rapid movement of sodium ions from extracellular to intracellular along their electromechanical gradient. Positively charged Na+ ions shift from the outside of the cell to the inside of the cell, causing the membrane potential to become more positive, now to approximately 0 mV (Fig. 1.1.4). The “fast” sodium channels inactivate within a few milliseconds, decreasing permeability of the cellular membrane to Na+ and preventing any further voltage increase.

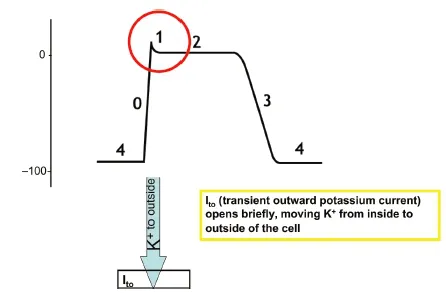

Phase 1 — Early Rapid Repolarization

Transient outward K+current, Ito, is turned on briefly by depolarization and drives the potassium out of the cell. This transient outward current rapidly inactivates, so the rapid outward current is brief, resulting in a slightly reduced intracellular charge as the positively charged K+ ions move outside of the cell (Fig. 1.1.5).

Phase 2 — Plateau Phase

The following ions are in motion in phase 2:

- Calcium moves slowly to the inside of the cell through the ICa-L channel (inward calcium channel)

- Potassium moves to the outside of the cell with the voltage and concentration gradient in an effort to equalize the voltage and the concentration of K+ within the inside and the outside of the cell

- Three sodium ions are moving into the cell in exchange for one calcium ion moving out of the cell

- The cumulative, simultaneous movement of these ions results in a stable voltage along the membrane or a “plateau phase” (Fi...