![]()

1

Introduction

This book is intended for students, engineers, and technically minded persons who want to learn more about smart card technology. It attempts to cover this broad topic as completely as possible, in order to provide the reader with a general understanding of the fundamentals and the current state of the technology.

We have put great emphasis on a practical approach. The wealth of illustrations, tables and references to real applications is intended to help the reader become familiar with the subject much faster than would be possible with a strictly technical approach. Consequently, this book is intended to be practically useful instead of academically complete. This is also the reason for making the descriptions as illustrative as possible. In places where we were faced with a choice between academic accuracy and ease of understanding, we have tried to strike a happy medium. Where this was not possible, we have given the preference to ease of understanding.

The book is structured such that it can be read in the usual way, from front to back. We have tried to avoid forward references as much as possible. The structure and content of the individual chapters are formulated to allow them to be read individually without any loss of understanding. A comprehensive index and a glossary allow this book to be used as a reference work. If you wish to know more about a specific topic, the references in the text and the annotated directory of standards will help you find the relevant documents.

Unfortunately, a large number of abbreviations have become established in smart card technology, as in so many other areas of technology and everyday life. This makes it particularly difficult for newcomers to become familiar with the subject. We have tried to minimize the use of these cryptic and frequently illogical abbreviations. Nevertheless, we have often had to choose a middle way between internationally accepted smart card terminology used by specialists and common terms more easily understood by laypersons. If we have not always succeeded, the extensive list of abbreviations should at least help overcome any barriers to understanding, which we hope will be short-lived. An extensive glossary at the end of the book explains the most important technical concepts and supplements the list of abbreviations.

An important feature of smart cards is that their properties are strongly based on international standards. This is also essential for interoperability, which is a fundamental requirement in most applications. Unfortunately, these standards are often difficult to understand, and in some problematic places they require outright interpretation. Sometimes only the members of the relevant standardization group can explain the intended meaning of certain sections. In such cases, The Smart Card Handbook attempts to present the meaning generally accepted in the smart card industry. Nevertheless, the relevant standards remain the ultimate authority, and in such cases they should always be consulted.

1.1 THE HISTORY OF SMART CARDS

The proliferation of plastic cards began in the USA in early 1950s. The low price of the synthetic material PVC made it possible to produce robust, durable plastic cards that were much more suitable for everyday use than the paper and cardboard cards previously used, which could not adequately withstand mechanical stresses and climatic effects.

The first all-plastic payment card for general use was issued by the Diners Club in 1950. It was intended for an exclusive class of individuals, and thus also served as a status symbol, allowing the holder to pay with his or her ‘good name’ instead of cash. Initially, only the more select restaurants and hotels accepted these cards, so this type of card came to be known as a ‘travel and entertainment’ card.

The entry of Visa and MasterCard into the field led to a very rapid proliferation of ‘plastic money’ in the form of credit cards. This occurred first in the USA, with Europe and the rest of the world following a few years later.

Today, credit cards allow travelers to shop without cash everywhere in the world. A cardholder is never at a loss for means of payment, yet he or she avoids exposure to the risk of loss due to theft or other unpredictable hazards, particularly while traveling. Using a credit card also eliminates the tedious task of exchanging currency when traveling abroad. These unique advantages helped credit cards become rapidly established throughout the world. Billions of cards are produced and issued annually.

At first, the functions of these cards were quite simple. They served as data storage media that were secure against forgery and tampering. General data, such as the card issuer's name, was printed on the surface, while personal data, such as the cardholder's name and the card number, was embossed. Many cards also had a signature panel where the cardholder could sign his or her name for reference. In these first-generation cards, protection against forgery was provided by visual features such as security printing and the signature panel. Consequently, the system's security depended largely on the experience and conscientiousness of the employees of the card-accepting organization. However, this did not represent an overwhelming problem, due to the card's initial exclusivity. With the increasing proliferation of card use, these rather rudimentary functions and security technology were no longer adequate, particularly since threats from organized criminals were growing apace.

Increasing handling costs for merchants and banks made a machine-readable card necessary, while at the same time, losses suffered by card issuers as the result of customer insolvency and fraud grew from year to year. It became apparent that the security features for protection against fraud and manipulation, as well as the basic functions of the card, had to be expanded and improved.

The first improvement consisted of a magnetic stripe on the back of the card, which allowed digital data to be stored on the card in machine-readable form as a supplement to the visual information. This made it possible to minimize the use of paper receipts, which were previously essential, although the customer's signature on a paper receipt was still required in traditional credit card applications as a form of personal identification. However, new approaches that rendered paper receipts entirely unnecessary could also be devised. This made it possible to finally achieve the long-standing objective of replacing paper-based transactions by electronic data processing. This required a different method to be used for user identification, which previously employed the user's signature. The method that has come into widespread general use involves a secret personal identification number (PIN) that is compared with a reference number in a terminal or a background system. Most people are familiar with this method from using bank cards in automated teller machines. Embossed cards with a magnetic stripe and a PIN code are still the most commonly used type of payment card.

However, magnetic-stripe technology has a crucial weakness, which is that the data stored on the stripe can be read, deleted and rewritten at will by anyone with access to a suitable magnetic card reader/writer. It is thus unsuitable for storing confidential data. Additional techniques must be used to ensure confidentiality of the data and prevent manipulation of the data. For example, the reference value for the PIN can be stored in the terminal or host system in a secure environment, instead of on the magnetic stripe in unencrypted form. Most systems that employ magnetic-stripe cards thus use online connections to the system's host computer for reasons of security, even though this generates significant costs for the necessary data transmission. In order to minimize costs, it is necessary to find solutions that allow card transactions to be executed offline without endangering the security of the system.

The development of the smart card, combined with the expansion of electronic data processing systems, has created completely new possibilities for devising such solutions.

In the 1970s, rapid progress in microelectronics made it possible to integrate nonvolatile data memory and processing logic on a single silicon chip measuring a few square millimeters. The idea of incorporating such an integrated circuit into an identification card was contained in a patent application filed by the German inventors Jürgen Dethloff and Helmut Grötrupp as early as 1968. This was followed in 1970 by a similar patent application by Kunitaka Arimura in Japan. However, real progress in the development of smart cards began when Roland Moreno registered his smart card patents in France in 1974. It was only then that the semiconductor industry was able to supply the necessary integrated circuits at acceptable prices. Nevertheless, many technical problems still had to be solved before the first prototypes, some of which contained several integrated circuit chips, could be transformed into reliable products that could be manufactured in large numbers with adequate quality at a reasonable cost.

The basic inventions in smart card technology originated in Germany and France, so it is not surprising that these countries played the leading roles in the development and marketing of smart cards.

The great breakthrough was achieved in 1984, when the French PTT (postal and telecommunication services authority) successfully carried out a field trial with telephone cards. In this field trial, smart cards immediately proved to meet all expectations with regard to high reliability and protection against manipulation. Significantly, this breakthrough for smart cards did not come in an area where traditional cards were already used, but in a new application. Introducing a new technology in a new application has the great advantage that compatibility with existing systems does not have to be taken into account, so the capabilities of the new technology can be fully exploited.

A pilot project was conducted in Germany in 1984–85, using telephone cards based on several technologies. Magnetic-stripe cards, optical-storage (holographic) cards and smart cards were used in comparative tests.

Smart cards proved to be the winners in this pilot study. In addition to a high degree of reliability and security against manipulation, smart card technology promised the greatest degree of flexibility for future applications. Although the older but less expensive EPROM technology was used in the French telephone card chips, newer EEPROM chips were used from the start in German telephone cards. The latter type of chip does not need an external programming voltage. An unfortunate consequence is that the French and German telephone cards are mutually incompatible. Further developments followed the successful trials of telephone cards, first in France and then in Germany, with breathtaking speed. By 1986, several million ‘smart’ telephone cards were in circulation in France alone. The total rose to nearly 60 million in 1990, and to several hundred million worldwide in 1997.

Germany experienced similar progress, with a time lag of about three years. These systems were marketed throughout the world after the successful introduction of the smart card public telephone in France and Germany. Telephone cards incorporating chips are currently used in more than 50 countries. However, the use of telephone cards in their original home countries (France and Germany), as well as in highly industrialized countries in general, has declined dramatically in the last decade due to the widespread availability of inexpensive mobile telecommunication networks and the general use of mobile telephones.

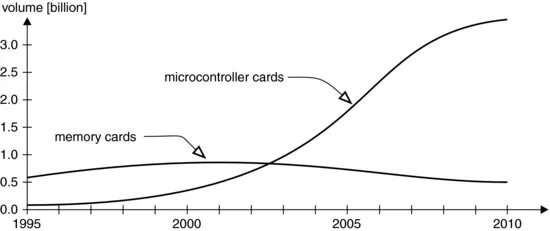

The integrated circuits used in telephone cards are relatively small, simple and inexpensive memory chips with specific security logic that allows the card balance to be reduced while protecting it against manipulation. Microprocessor chips, which are significantly larger and more complex, were first used in large numbers in telecommunication applications, specifically for mobile telecommunication. The production trends of smart cards with memory chips (memory cards) and smart cards with microprocessor chips (microcontroller cards) in recent years are shown in Figure 1.1.

In 1988, the German Post Office acted as a pioneer in this area by introducing a modern processor card using EEPROM technology as an authorization card for the analog mobile telephone network (C-Netz). The reason for introducing such cards was an increasing incidence of fraud with the magnetic-stripe cards used up to that time. For technical reasons, the analog mobile telephone network was limited to a relatively small number of subscribers (around one million), so it was not a true mass market for processor cards. However, the positive experience gained from using smart cards in the analog mobile telephone system was decisive for the introduction of smart cards in the digital GSM network. This network was put into service in 1991 in various European countries and has presently expanded over the entire world, with more than three billion subscribers in nearly every country of the world.

Progress was significantly slower in the bank card area, in part due to the more stringent security requirements and higher complexity of bank cards compared with telephone cards. These differences are described in detail in the following chapters. Here we would just like to remark that the development of modern cryptography has been just as crucial for the proliferation of bank cards as developments in semiconductor technology.

With the widespread use of electronic data processing in the 1960s, the discipline of cryptography experienced a sort of quantum leap. Modern, high-performance hardware and software made it possible to implement complex, sophisticated mathematical algorithms in single-chip processors, which allowed previously unparalleled levels of security to be achieved. Moreover, this new technology was available to everyone, in contrast to the previous situation in which cryptography was a covert science in the private reserve of the military and secret services.

With these modern cryptographic algorithms, the strength of the security mechanisms in electronic data processing systems could be mathematically calculated. It was no longer necessary to rely on a highly subjective assessment of conventional techniques, whose security essentially rests on the secrecy of the methods used.

The smart card proved to be an ideal medium. It made a high level of security (based on cryptography) available to everyone, since it could safely store secret keys and execute cryptographic algorithms. In addition, smart cards are so small and easy to handle that they can be carried and used everywhere by everybody in everyday life. It was a natural idea to attempt to use these new security features for bank cards, in order to come to grips with the security risks arising from the increasing use of magnetic-stripe cards.

The French banks were the first to introduce this fascinating technology in 1984, after completion of a pilot project with 6000 cards in 1982–83. It took another 10 years before all French bank cards incorporated chips. In Germany, the first field trials took place in 1984–85, using a multifunctional payment card incorporating a chip. However, the Zentrale Kreditausschuss (ZKA), which is the coordinating committee of the leading German banks, did not manage to issue a specification for multifunctional Eurocheque cards incorporating chips until 1996. In 1997, all German savings associations and many banks issued the new smart cards. In the previous year, multifunctional smart cards with POS capability, an electronic purse, and optional value-added services were issued in all of Austria. This made Austria the first country in the world to have a nationwide electronic purse system.

An important milestone for the future worldwide use of smart cards for making payments was the adoption of the EMV specification, a product of the joint efforts of Europay, MasterCard and Visa. The first version of this specification was published in 1994. It provides a detailed description of the operation of credit cards incorporating processor chips, and it ensures the worldwide compatibility of the smart cards of the three largest credit card organizations. Hundreds of millions of EMV cards are presently in use worldwide.

With a delay of around ten years relative to normal contact smart cards, the technology of contactless smart cards has developed to the point of market maturity. With contactless cards, an electromagnetic field is used to supply power to the cards and exchange data with the terminal, without any electrical contact. The majority of currently issued EMV cards use this technology to enable fast, convenient payment for small purchases.

In the 1990s, it was anticipated that electronic purses, which store money in a card and can be used for offline payment, would prove to be another driver for the international proliferation of smart cards for payment transactions. The first such system, called Danmøntnt}, was put into service in Denmark in 1992. There are presently more than twenty national systems in use in Europe alone, many of which are based on the European EN 1546 standard. The use of such systems is also increasing outside of Europe. Payment via the Internet offers a new and promising application area for electronic purses. However, a satisfactory solution to the difficulties involved in using the public Internet medium to make payments securely but anonymously throughout the world, including small payments, has not yet been found. Smart cards...