eBook - ePub

The Tibetans

About this book

This book provides a clear and comprehensive introduction to Tibet, its culture and history.

- A clear and comprehensive overview of Tibet, its culture and history.

- Responds to current interest in Tibet due to continuing publicity about Chinese rule and growing interest in Tibetan Buddhism.

- Explains recent events within the context of Tibetan history.

- Situates Tibet in relation to other Asian civilizations through the ages.

- Draws on the most recent scholarly and archaeological research.

- Introduces Tibetan culture – particularly social institutions, religious and political traditions, the arts and medical lore.

- An epilogue considers the fragile position of Tibetan civilization in the modern world.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Vessel and Its Contents

“Tibet” means many things. Geographically, it designates the vast uplift, popularly referred to as the “roof of the world,” that extends from the Himalaya to the great deserts of Inner Asia. Linguistically, it embraces those regions, from northern Pakistan to China’s Gansu Province, in which varieties of the Tibetan language are spoken. In its socioeconomic dimensions Tibet may be thought of in terms of its dominant modes of production: high-altitude pastoralism and a barley-based agriculture. Culturally Tibet is distinguished by the use of classical Tibetan as a literary medium, by shared artistic and craft traditions, and by the important role of the religious system of Tibetan Buddhism. Politically, according to one’s ideological standpoint or historical frame of reference, Tibet may be a particular administrative unit of the contemporary People’s Republic of China, the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), or else the much vaster territory that, nominally at least, came under the rule of the Fifth Dalai Lama during the seventeenth century, which many Tibetans still see as defining their rightful political domain. Depending upon the story one wishes to tell, therefore, one must first choose among several distinct, but nevertheless overlapping, Tibets.

Though cultural and historical Tibet will be our main concern throughout this book, it is impossible to consider this apart from the distinctive geographical and ecological zone formed by the Tibetan plateau and its equally distinctive population of farmers and nomads, whose livelihoods are based respectively on the cultivation of highland barley and the husbandry of sheep and yak, and who for the most part speak languages that are part of the tightly knit linguistic system of Tibetan. These people have not always considered themselves to be Tibetans, and do not always so consider themselves today, but in most cases they regard their culture and history as intimately tied to Tibet under one description or another. We will begin, therefore, with a general sketch of the Tibetan environment and its inhabitants – the “vessel and its contents” according to a traditional locution – and also of the language through which the Tibetan cultural sphere is in some measure defined.

High Peaks, Pure Earth

A popular legend provides a useful entry into the “land of snows.” At some time in the distant past, Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, gazed upon our world with the intention of saving the creatures of Tibet. He looked and looked, but could find no hint that the Buddha had visited that land, or that his teaching had ever reached it. What Avalokiteshvara saw, as he continued his inspection, was a great area of darkness, which seemed to him to be without doubt the worst place on earth. Not long before, it had been a vast sea, but now that the waters had receded it appeared that the high regions of western Tibet were encircled by glacial mountains and fractured by ravines. Herds of hoofed animals roamed wild there. With its glaciers and lakes, feeding the rivers that flowed from the high plateau, this region resembled a reservoir. In the middle elevations of the plateau were grass-covered valleys interrupted by rocky massifs, where apes and ogresses made their lairs in caves and sheltered hollows. Broken up by the great river valleys, this part of Tibet seemed like the fractured terrain surrounding an irrigation canal. And following the plateau’s descent to the east, the bodhisattva saw forests and pasturelands, where birds of all kinds and even tropical creatures were to be found. This looked to him like land made fertile by irrigation. Still, with all the power of his divine sight, Avalokiteshvara could find no candidates for discipleship in Tibet, for no human beings were yet to be seen there.1

The tale of the bodhisattva’s first glimpse of Tibet serves to direct our vision to several key features of the Tibetan landscape. For much of Tibet was indeed formerly at or beneath sea level; in this the legend accords with geological fact. Roughly forty-five million years ago, as the Indian tectonic plate collided with and began to be drawn underneath Southern Tibet, then the south coast of continental Asia, the bed of the ancient Tethys Sea that had separated the continents began to rise. The ensuing uplift gave birth to the Himalaya and contributed to the formation of the other great mountain ranges of Inner Asia: Karakorum, Pamir, Tianshan, and Kunlun. During subsequent cycles of glaciation, many lakes, large and small, were also formed on the rising plateau. Following the last great Ice Age, these began to recede – in some places one finds ancient shorelines as much as 200 meters above present water levels – and, because they were frequently without outlet, they became rich in salts and other minerals, trade in which has played an essential role in the traditional economy. So not without reason do the old legends speak of a primordial ocean covering Tibet. The ongoing subduction of the Indian subcontinent, moreover, means that the Tibetan plateau (also called the Tibet-Qinghai plateau) is still in formation and is especially prone to earthquake. With a mean elevation of over 12,000 feet and an area of some 1.2 million square miles, it is by far the most extensive high-altitude region on earth. Roughly speaking, the Tibetan plateau embraces one-third of the territory of modern China and is the size of the entire Republic of India, or nearly half the area of the lower forty-eight among the United States. To appreciate Tibet as a human habitat, therefore, its sheer immensity must first clearly be grasped.

Tibet is further depicted in our tale as a wilderness, a place that came to be peopled and tamed only at a relatively late date through the divine agency of the bodhisattva, a civilizing influence originating from beyond the frontiers of Tibet itself, perhaps a mythical reflection of the fact that much of Tibet was settled in comparatively recent times. Indeed, in some Himalayan districts, Tibetan settlement dates back only a few centuries. The origins of the Tibetan people will be considered in more detail in the following chapter, but here we should note that populations on the plateau were always comparatively thin. If the current ethnic Tibetan population of China, about 5.5 million, offers any indication, the population density of the Tibetan plateau could seldom have been much more than three or four persons per square mile, and for most of Tibet’s history even less. Of course, the population is concentrated in habitable areas that comprise only a fraction of the Tibetan geographical region overall; it has been estimated, for instance, that only about 1 percent of the Tibetan plateau sustains regular agricultural activity. Still, the dispersal of the populace over a vast, inhospitable terrain was clearly a factor inhibiting early civilizational development.

When Avalokiteshvara gazed upon Tibet, he saw three main geographical zones. The tripartite division of the Tibetan plateau into its high and harsh western reaches, the agricultural valleys of its mid-elevations, and the rich pasturage and forested lowlands as one descends towards China schematically depicts the topography of the land as one moves from west to east. In comparing the land to an irrigation system, with its reservoir, channel, and fields, the story underscores the central role of the control of water resources in the emergence of civilization in Tibet. Indeed, the Tibetan term for governmental authority (chapsi), literally “water-regime,” derives from the polite and honorific word for water, chap.

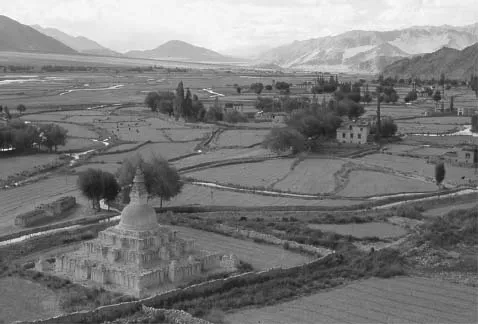

Figure 1 Irrigation works in the Indus River Valley, Ladakh, 1975.

In traditional Tibetan geographical terms, the three zones described by the bodhisattva correspond to the three great divisions of Tibet: (1) the “three circuits” of Ngari in the west, (2) the “four horns” of Ü (the “Center”) and Tsang, and (3) the “six ranges” or “three realms” constituting the eastern provinces of Amdo and Kham. The first embraces the territories of the ancient Zhangzhung and later Gugé kingdoms, centered in the areas around Mt. Kailash (alt. 6,714 meters) that now constitute the Ngari Prefecture (Ch. Alizhou) of the Tibet Autonomous Region. The “three circuits” (whose exact enumeration is treated variously in different sources) also include the regions of Ladakh and Zangskar, now in India’s Jammu and Kashmir State, and neighboring locations in Himachal Pradesh, as well as in former times Baltistan in far northern Pakistan. (Baltistan was in most respects removed from the Tibetan cultural sphere following its conversion to Islam after the fifteenth century.) The area as a whole is characterized by high desert and pasture, with numerous salt lakes, and is subject to very severe winter conditions, temperatures in some places regularly plunging to minus 50° Fahrenheit. Irrigated river valleys, whose fresh waters spring from glacial sources in the high mountains, permit crops to be grown, though there is evidence that desiccation during the past millennium has reduced the land available for agriculture in some parts of Ngari. Indo-European peoples were among the early inhabitants in this area – so, for instance, the Dardic-speaking populations of ancient Ladakh – and the region as a whole was integrated into the Tibetan cultural sphere only gradually following the seventh-century expansion of the Tibetan empire. The “three circuits” of Ngari are at present the most thinly populated part of the Tibetan world, the home of not more than four or five percent of all Tibetans. The barren beauty of the desert, dominated by endlessly varying formations of rock and mountain, was nicely captured in the remark of a leading lama in Ladakh on recalling the impression made by news of the Apollo moon landing in 1969: “We Ladakhis have never been motivated to visit the surface of the moon because we had it here all along.”2

Figure 2 A typical landscape in western Tibet, 1985.

The provinces of Ü (often referred to simply as “central Tibet”) and Tsang (the region to the west of Ü, with the town of Shigatsé as its main center) form the traditional Tibetan heartland, whose chief arteries are the Yarlung Tsangpo River (often just “Tsangpo”), which in India becomes the Brahmaputra, and its tributaries. (The “four horns” into which these parts of Tibet are subdivided are ancient administrative divisions, as will be explained in Chapter 3 below.) Alluvial plains support relatively prosperous farming in many places here, such as the Nyang River valley in the vicinity of Gyantsé in Tsang, and the Yarlung Valley in Ü. Lhasa, the capital of Tibet in modern times, is located in one such valley, that of the Kyi River in Ü. The climate in the central river valleys is relatively mild, with warm summers and temperatures rising above freezing on sunny days even during the coldest months of the year. Higher valleys in the mountains separating the tributaries of the Tsangpo permit grazing in relatively close proximity to arable land, so that a mixed agricultural-pastoral economy is often the norm. To the north of Ü-Tsang, extending west into Ngari and northeast toward Amdo, is the high plateau called the Jangtang (the “northern plain”), whose inhabitants are exclusively pastoralists. The imposing Nyenchen Tangla range, the highest summit of which soars to 7,088 meters, traverses central Tibet and is regarded as the abode of that region’s principal protective divinity, while two of Tibet’s greatest lakes, Nam Tso (or Tengri Nor, “Heaven’s Lake,” as it is known in Mongolian) and Yamdrok Tso, are prominent among the waters of the central region.

Figure 3 A Central Tibetan ferryman with his kowa, a yak-hide boat resembling a coracle, on the Kyi River near Lhasa, 1984.

Traveling to the east and southeast, one reaches some of Tibet’s lowest elevations as one descends towards eastern India from the districts of Dakpo, Kongpo, and Powo. Here one finds rich forest and abundant water resources. The dietary importance of fish in some places, and the cultivation of such crops as rice and millet in the lower valleys, distinguishes the way of life in these parts from the basic economy as known elsewhere. This is a transitional zone communicating with the adjacent territories of South Asia, including Bhutan and India’s Arunachal State, regions where Tibetan culture has long been influential. The great bend of the Tsangpo River, which turns here to dive into India, forms the deepest gorge in the world, dominated by the great summit of Namchak Barwa (alt. 7,756 meters), the “blazing meteor.” Further descent leads to the region of Pemakö, a “hidden land” that came to be regarded in Tibetan legend as a paradise on earth. Its subtropical environment was described by Chögyam Trungpa (1939–87), a celebrated teacher from Kham who passed this way en route to exile in India in 1959:

We crossed … a slender bamboo bridge and, beyond it, found ourselves on steep hard ground. There were no rocks, but footholds had been cut on the stony surface in a zig-zag pattern to make the climb easier. As we went further up we could see the Brahmaputra again, now on its southwestward course: the ranges on its south side looked very beautiful with patches of cloud and little groups of houses dotted about. These foothills of the Himalayas have a continual rainfall and everything looked wonderfully green. We could not recognize most of the plants here for they were utterly different from those which grow in East Tibet.3

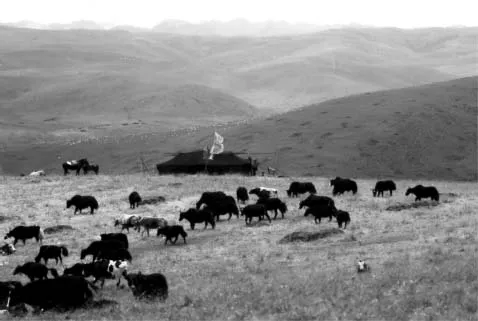

The eastern reaches of traditional Tibet are the vast expanses of Kham and Amdo, now divided among five provinicial units in China. Kham today comprises the western parts of China’s Sichuan Province, together with adjacent districts in the Tibet Autonomous Region and northern Yunnan; Amdo corresponds to Qinghai Province, with some neighboring parts of Gansu and northern Sichuan. Both Kham and Amdo are characterized by abundant, rich pastureland, making their nomads some of the most prosperous Tibetans. To the west and north of Amdo, the steppe becomes desert as one approaches Gansu and Xinjiang, while to its southeast, as well as in the river valleys throughout Kham, wheat, barley, and other crops may be cultivated. Intervening between the eastern districts of Kham and Amdo, in the Jinchuan river system of Sichuan, is the region known in Tibetan as Gyelmorong, whose people, though speaking a group of distinct languages, have nevertheless long considered themselves Tibetans and are adherents of the Tibetan Bön or Buddhist religions. To one degree or another, similar patterns of Tibetanization of originally non-Tibetan populations may be found throughout the eastern reaches of Amdo and Kham. Among the Yi of Sichuan, the Naxi of Yunnan, and the Tu of Qinghai, for instance, Tibetan culture has long played an important role. Other groups – the Minyakpa of Chakla in far eastern Kham are an example – would be indistinguishable from neighboring Tibetan populations were it not for the non-Tibetan origin of their local language.

Figure 4 Yak and hybrid cattle grazing at a nomad camp in Ngaba, Sichuan Province, 1990.

The metaphor of the reservoir and irrigation canal, which we have seen applied to Tibet in particular, pertains too to the Tibetan plateau in its relation with South and East Asia. The Indus and one of its major tributaries, the Sutlej, rise in Ngari and bring their waters to the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent in Himachal Pradesh, Kashmir, and the Punjab. Other major rivers originating in Ngari, including the Gandaki, which descends to join the Ganges, and the Tsangpo, figure prominently among the essential water resources of northeastern India, Nepal, and Bangladesh. The origins of these rivers in the area around Mt. Kailash led early on to that mountain’s becoming analogically regarded as Himavat, the legendary mountain of ancient Indian Buddhist cosmology, adjacent to the Anavatapta lake, from which, in spiral courses, four great rivers descend. As we read in verses attributed to the poet-saint Milarepa (1040–1123):

The lord of glacial peaks

Resembles a divine mound of white butter

At the head of four rivers:

To the east, the mountain of incense perfume,

Where the turquoise lake Mapam’s waters are gathered;

To the south, the defile of the golden ledge;

In the west is the eight-peaked mountain king;

And in the north, the indigo meadow, the meadow of gold.4

Resembles a divine mound of white butter

At the head of four rivers:

To the east, the mountain of incense perfume,

Where the turquoise lake Mapam’s waters are gathered;

To the south, the defile of the golden ledge;

In the west is the eight-peaked mountain king;

And in the north, the indigo meadow, the meadow of gold.4

Proceeding east from the Tsangpo-Brahmaputra gorges, southeastern Tibet and Kham are scored by a series of important rivers that sustain life throughout Southeast Asia and southern China. The Salween (Tib. Ngülchu), rising in Tibet’s northern plain in the region of Nakchu, descends into Burma, while the Mekong (Tib. Dachu) wends its way from Nangchen in Kham down through Laos and Vietnam. As they leave Tibetan territory, the parallel courses of these two great rivers are separated by the summits of the Kawa Karpo range (6,740 meters), prominent among Tibet’s sacred mountains. Further east, the two major tributaries of the Yangzi, the Jinsha River (Tib. Drichu) and Yalong River (Tib. Dzachu), define the principal regions of Kham. Along the length of the Jinsha, from north to south, lie many of Kham’s major centers, including Jyekundo, Ling, Dergé and Batang. Situated in the area between the rivers are the districts of Ganze, Nyarong, and Litang. East of the Yalong one approaches the Chinese cultural sphere in Sichuan via the still Tibetanized regions of Gyelmorong and Minyak Chakla, the latter dominated by the massif of Minyak Gangkar (7,555 meters). It is here that the town of Dartsedo (Ch. Kangding, formerly Dajianlu), serves as an entrepôt linking the Tibetan and Chinese worlds.

The northeastern province of Amdo is the source of the Yellow River (Tib. Machu) and is dominated by the heights of Amnyé Machen (6,282 meters). Amdo Tso-ngön, the “blue lake of Amdo,” known as Kokonor in Mongolian and Qinghai in Chinese, lends its name to the region as whole. The Yellow River valley to the east of the Kokonor includes the richest agricultural lands in the region and is a zone of considerable ethnic diversity, with Tu, Salar, Chinese Muslim (Hui) and other populations. Amdo also has long had a substantial Mongol presence, particularly in the prairies to the north and southwest of the Kokonor. In the southeast of Amdo are the Tibetan districts of Repkong (Ch. Tongren) and Luchu (Ch. Gannan, “southern Gansu”). One reaches the northeastern extremity of the Tibetan world in the district of Pari (Ch. Tianzhu) in Gansu, famed for its herds of white yak. Like the far west of Tibet, the northeast is subject to remarkably harsh winter conditions. Here, as throughout much of the Jangtang, summer snow is a regular occurrence.

Tibetan geographical nomenclature distinguishes several kinds of terrain in terms of natural features and human use. The main agricultural areas are known by the term for cultivated fields, zhing, while tang, “plain,” generally designates the high plateau on which only pastoral activity is possible. “Highland,” gang, describes the elevated ridges and ranges dividing river systems and agricultural terrain, and drok is used for the pasturage found in the uplands. Farmers are zhingpa, “those of the fields,” while the nomads are drokpa, “those of the pastures.” A special term sometimes refers to those who pursue a mixed agricultural and pastoral livelihood, samadrok, literally, “neither earth nor pasture.” The deep valleys to the south and east of Tibet, leading into South Asian and Chinese territories respectively, are frequently called rong and the term rongpa, “valley folk,” often applies to the non-Tibetan peoples inhabiting these lower regions.

Though the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara was concerned that the Tibet he inspected was still unpopulated, he took note nevertheless of its rich wildlife. Among the hoofed animals whose herds he observed he would have remarked several species of wild sheep, including bharal sheep and argali, as well as deer, gazelle, and the so-called Tibetan antelope (chiru). The Tibetan wild ass (kyang) would have been especially plentiful, as indeed it was until the mid-twentieth century, when large-scale extermination greatly reduced populations in the TAR. Seeking what was most iconic of Tibet, he might have gazed with admiration and awe upon the wild yak, or drong, described here in the words of the naturalist George Schaller:

While walking in the Chang Tang [Jangtang], I occasionally met several yak bulls ponderously at rest on a hillside. They would rise and face me with their armored heads before fleeing. Their mantles of hair...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- List of Figures

- List of Maps

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- A Note on Transcription and Translation

- Maps

- 1 The Vessel and Its Contents

- 2 Prehistory and Early Legends

- 3 The Tsenpo’s Imperial Dominion

- 4 Fragmentation and Hegemonic Power

- 5 The Rule of the Dalai Lamas

- 6 Tibetan Society

- 7 Religious Life and Thought

- 8 The Sites of Knowledge

- 9 Tibet in the Modern World

- Notes

- Spellings of Tibetan Names and Terms

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Tibetans by Matthew T. Kapstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Cultural & Social Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.