eBook - ePub

The Intelligent Portfolio

Practical Wisdom on Personal Investing from Financial Engines

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Intelligent Portfolio

Practical Wisdom on Personal Investing from Financial Engines

About this book

The Intelligent Portfolio draws upon the extensive insights of Financial Engines—a leading provider of investment advisory and management services founded by Nobel Prize-winning economist William F. Sharpe—to reveal the time-tested institutional investing techniques that you can use to help improve your investment performance. Throughout these pages, Financial Engines' CIO, Christopher Jones, uses state-of-the-art simulation and optimization methods to demonstrate the often-surprising results of applying modern financial economics to personal investment decisions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Intelligent Portfolio by Christopher L. Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Personal Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Now It’s Personal

The future ain’t what it used to be.

—Yogi Berra (1925-)

Over the last few decades, there has been a profound shift in investment responsibility - away from the professional institutions that traditionally manage financial assets and right into your lap. Today, tens of millions of people are faced with making personal investment decisions that will have a big impact on their future quality of life - but only a few feel like they know what they are doing. This shift in responsibility is not simply the result of some cyclical government policy change or a conspiracy among big corporations to avoid funding retirement for their employees, but rather it is a necessary response to a global population that is rapidly aging. In the future, whether you like it or not, you are going to be responsible for managing your retirement investments. The good news is that within the last 10 years, changes in technology have opened the door to the widespread use of modern financial economic methods in personal investing. For the first time, it is possible to apply the same rigorous techniques used by the largest institutional investors to personal investment choices. In this chapter I explore these techniques, how they became available to individual investors, and how they enable a powerful new way of looking at personal investment decisions—outcomes-based investing.

How the heck did we end up here?

Since when did it become accepted that truck drivers, marketing analysts, lawyers, bakers, computer programmers, dentists, and teachers should all become expert investment managers? Who decided that we all need to become well-versed in mutual fund selection and dealing with the impact of investment risk? I don’t recall voting on this, do you?

If you are reading this book, chances are that you have at least a passing interest in becoming a better investor. For some people, the subject of investing is a passion or a hobby, for others it is more of a reluctant obligation - like cleaning the house. The reality is that we now live in a world that expects everyday people to understand a great deal about investing. Expectations go far beyond how to balance a checkbook or apply for a credit card. Today, virtually everyone over the age of 18 is expected to understand concepts such as the value of compounding, progressive tax rates, the differences between equities and bonds, and the benefits of tax-deferred savings. Those who do not bother to acquire this knowledge are roundly criticized by TV commentators, newspaper editors, and personal finance gurus for being dangerously out of touch. The era of the self-directed investor has truly arrived - even if most of us were not ready for it.

Unfortunately, investing is a sprawling and complicated subject, rich with intimidating jargon and numerous conflicts of interest thrown in for good measure. It is no surprise that many people approach investing decisions with a sense of dread, or at least acute anxiety. Why do I have to make all these investment decisions? Generally speaking, I am not expected to diagnose the strange knocking sound coming from the hood of my car on my own, nor am I presumed to figure out the origin of a blotchy rash on my son’s back without expert help. Somehow, when it comes to investing, the prevailing opinion seems to be that you need to be educated enough to make good decisions on your own. But most people have better things to do with their lives than to become self-educated investment experts. And so, here we are, with tens of millions of individual investors directing how trillions of dollars of retirement money is invested, and bearing the consequences of those decisions for better or worse.

But why? Is this really the best way to make sure that we retire comfortably? It turns out that the dramatic movement towards more individual responsibility in retirement investing has its roots in a more fundamental and irreversible trend - we are all living quite a bit longer than we used to.

A CHANGING WORLD

Sixty years ago in the United States, things were a bit different. Back then, there were fewer decisions left to individuals. Mostly such choices were out of your hands. In the past, retirement was based on the concept of a three-legged stool, represented by family, government, and the employer. For much of recorded history, the most important leg of the stool (and often the only one) was your family. It was generally accepted that when you got old, your kids or extended family would take care of you (assuming you had any and that you had been nice to them). This was generally not an undue burden, as families were larger and most relatives tended to live in close proximity to one another. Moreover, retired people did not typically live that long after they stopped working. You might find it hard to believe, but for a male born in 1900, the National Center for Health Statistics reports that the average expected life span was only 48 years. Often, people would simply work until they were no longer able to continue on. Of course, things are a bit different today. Families are smaller and often spread out across large geographic distances. We are also living much longer. By 2003, the average 65 year-old woman in the United States could expect to live an additional 20 years. Moreover, steady advances in medical technology continue to increase average life spans. With earlier retirement dates, and longer life spans, retirement is now often measured in terms of several decades, not years.

In the summer of 1935, another leg of the stool was added—Social Security . With Franklin Roosevelt’s signing of the Social Security Act, the U.S. government would provide a safety net for those in retirement of a lifetime guarantee of income. Social Security was a monumental change in public policy, and is one of the enduring legacies of the modern welfare state. When the system was created, however, there was a large working population paying into the system to support a relatively small retired population. Now, with the aging of the baby boomer population, the system’s finances are under strain. Under current course and speed, either benefits will have to be reduced or payroll taxes will have to be significantly increased (or both) in order to fund the promised benefits, due to the growing population of retirees. Reaching such a political compromise has proven to be a difficult task in recent years, and so the magnitude of the funding problem continues to grow. Of course, this stalemate has potential serious consequences for taxpayers like you and me.

The third leg of the retirement security stool (at least in the last 50 years or so) was the employer. For those lucky enough to work for large companies, defined benefit (DB) plans often provided generous guarantees of retirement income, if you stuck with your employer sufficiently long. A DB plan provided employees with a guarantee of future retirement income funded from a pool of assets managed by the employer (usually without any input from the employees). The money was professionally managed on the employees’ behalf, and if the markets went down, the company made contributions to the plan to insure the benefits were appropriately funded. If you were part of such a plan, all you had to do was show up to work each day for 30 years or so, and you were often comfortably set for retirement. However, even in their heyday, defined benefit plans were not available to everyone. It is estimated that only about a third of people over the age of 55 receive any form of pension income.1 In many situations, employees failed to qualify for any DB income because they changed jobs before they became eligible for the plan, or the companies they worked for simply did not offer such pension benefits. In the most recent generations, the availability of DB pension plans for new employees has declined dramatically.

Why are DB plans going away? One significant factor is the fact that people in today’s economy tend to change jobs frequently. Under a traditional defined benefit plan (which provides guaranteed benefits), an employee must stay with a single employer for more than 10 years or more to accumulate significant retirement benefits. When the concept of “employment for life” was more popular, these restrictions were not as big a problem. However, today, most people change jobs multiple times during their careers, and hence would not accumulate significant benefits under the traditional defined benefit structure. But the biggest reason for the demise of DB plans is cost. It is increasingly expensive to run a defined benefit plan.

Most companies invest their defined benefit plan assets in a broadly diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds that is used to pay the future income of retired workers. If the market goes down, the company is obligated to make additional payments into the plan to ensure that it can pay out its promised retirement benefits. However, this creates a potential problem for companies such as General Motors and Ford, with large retired populations relative to their current workforce. With a DB plan, the company may have to come up with more money to fund the plan at precisely the time when money is scarce. When stock market returns are poor, chances are that the company is also feeling the pinch from a downturn in its business. The need to make payments into the plan when markets are down and when the cost of those payments to the company is highest (more on this concept later) makes DB plans a potentially expensive and risky proposition.

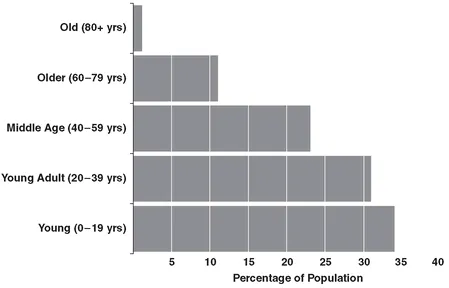

The magnitude of this cost problem is further accentuated when we take into account the impact of an aging population. Because we are all living longer, on average, the number of older retired people has grown dramatically over time, while, at the same time, birth rates have declined significantly. The following figure is an example of a population pyramid chart using 1950 data from the United States Census Bureau.2 Such graphics are called pyramid charts due to their distinctive shape, consistent with the distribution of age groups in a growing population. Historically, in most societies, there have been a large number of young people relative to the population of older persons. If the age of the population is plotted on the vertical axis, and the length of the bars represent the proportion of the population in that age group, you get a distinctive triangle shape. In the United States of 1950, this pattern was clearly evident, as shown in Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1 U.S. Population by Age Group in 1950

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

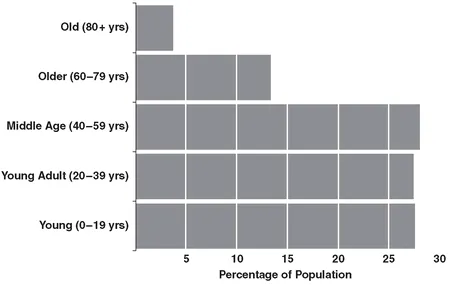

In 1950, the U.S. population was growing fast, and while life spans were gradually increasing, the proportion of older people had not yet begun to grow disproportionately. Now contrast this with the picture in 2006 (Figure 1.2).

The combination of lower average birth rates and greatly increased longevity has dramatically changed the relative proportions of active workers supporting retirees. For instance, in 1950, there were 47 people in their prime working years (between the ages of 20 and 59) for every person age 80 or older. By 2006, this ratio dropped to only 15—a decline of 68 percent. By 2050, there will be only 6 employees in their prime working years for every person age 80 or older. This implies a very different division of resources between generations than what has been historically observed.

The net effect of this demographic shift is that companies (and many governments) are increasingly unable to afford guaranteed income for life to the growing retiree population. If you guarantee income for retirees, it means working employees must fund this income with increasingly high taxes, or they must be willing to assume the financial risk of pension assets falling short when markets turn sour. When there are only a small number of retirees for each worker, as was historically the case, this is not such a big problem. But when the retiree population gets large, look out. The burden on the working population becomes too onerous. Just as a company that takes on too much debt greatly increases the risk to stockholders and employees, guaranteeing retirement income for an ever-increasing retiree population is not an economically sustainable proposition. If retirees don’t have any risk in their retirement income, then existing workers must assume all the risk. But now there are simply too many retirees to support—something has to give. The only way out of this predicament is to have the retired population share the risk of market downturns with the working population—that is, to make individual retirement income dependent on market performance. Enter the 401(k).

FIGURE 1.2 U.S. Population by Age Group in 2006

Source: U.S. Census Bureau.

THE GRAND SOCIAL EXPERIMENT: 401 (k)

In the last 20 years, the United States has seen enormous growth in Defined Contribution (DC) plans such as the 401(k). What was once an obscure part of the tax code, the 401(k) plan is now the primary retirement vehicle for most U.S. workers. In fact, DC plan assets now exceed the total value of DB plans by a wide margin. In 2006, according to the Federal Reserve, DB plans totaled $2.3 trillion, while DC plan assets totaled more than $3.3 trillion.3 Defined contribution plans differ from DB plans in that the individual is responsible for making the investment decisions and for bearing investment risk, not the employer. With the rising prevalence of 401 (k) plans, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), Health Savings Accounts (HSAs), 529 Plans, and other plans where individuals must manage their assets, more and more financial responsibility is being placed squarely on the shoulders of everyday people.

In many ways this is a grand social experiment—never before has so much financial responsibility been in the hands of so many nonexperts. We do not yet know what the results of the experiment will be for the United States. If financial markets perform well in the coming decades, people save aggressively and invest prudently, the experiment will likely be successful. However, if this rosy state of the world does not come to pass—there are going to be a lot of grumpy and cash-strapped retirees wondering how all this came to be.

The rise of defined contribution plans like the 401(k) has dramatically altered the landscape for individual investors. As of 2006, there are now more than 55 million individuals managing trillions of dollars of defined contribution assets.4 For most employees hired in the last decade or so, the defined contribution plan is their principal (and often only) retirement benefit. In fact, DC assets now account for 61 percent of overall retirement assets in the United States. Importantly, there is no turning back from this trend. Since the economic need for defined contribution plans like the 401(k) is based on long-term demographic trends, there is no going back to the days of guaranteed retirement benefits. In the future, your retirement paycheck will depend to some extent on market performance and how you choose to allocate your investments. Put another way, if markets decline, you will be the one holding the bag—not your employer.

THE KNOWLEDGE GAP

Sadly, our educational system has been woefully behind the curve in preparing people for the heavy new financial responsibilities of a self-directed investment world. Unless you happen to work in financial services, what you know about these subjects is likely to have come from friends, family, and the media, not from high school or college coursework in economics and finance. Relatively few people have any significant exposure to academic finance or economics, and hence many of the important concepts that govern good decision-making are unknown to those who could benefit from them. Much of what we do learn is incomplete and reduced to three bullet-point sound bites on talk radio or cable TV shows. Most people rely on a haphazard mix of conventional wisdom,...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1 - Now It’s Personal

- CHAPTER 2 - No Free Lunch

- CHAPTER 3 - History Is Bunk

- CHAPTER 4 - The Wisdom of the Market

- CHAPTER 5 - Getting the Risk Right

- CHAPTER 6 - An Unnecessary Gamble

- CHAPTER 7 - How Fees Eat Your Lunch

- CHAPTER 8 - Smart Diversification

- CHAPTER 9 - Picking the Good Ones

- CHAPTER 10 - Funding the Future

- CHAPTER 11 - Investing and Uncle Sam

- CHAPTER 12 - Wrapping it Up

- Appendix - The Personal Online Advisor

- Notes

- Glossary

- About the Author

- Index