![]()

Part I

What Happened?

![]()

Chapter 1

A Short History of the Crisis

With the financial crisis still bubbling as we write in late 2009, we will first consider its roots and its potential impact in order to set a context for the later chapters.3 We show that some of the factors leading to the events of 2006-9 were anomalous, others will continue, but that the effects will be felt well into the next decade. Governments and consumers in the West will be particularly constrained as they tackle paying off their debt. In the meantime, the newly industrialising economies enjoy many advantages: their savings are high, their labour cheap and skilful, their access to technology is rapidly approaching that of the Western economies and many have large internal markets. All of this presents a competitive threat to established industrial powers.

The roots of the financial crisis

The financial crisis that began in 2006-7 with defaults on ‘sub-prime’ mortgages in some parts of the USA serves as a decisive punctuation mark. It marked the end of a period of ‘fake’ stability, one in which all the indicators seemed to support a mode of operation and a set of assumptions that we now have to question. We begin this chapter with a review of the roots of the crisis, in the view that to fully understand where we’re going, we need first to mark where we are.

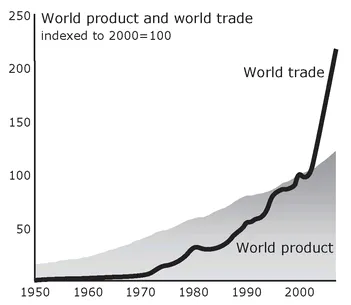

Figure 1.1 World product and world trade

We have been through a period of asset price inflation. Figure 1.1 shows a simple plot of world trade against world product, both in money of the day, from 1950 to the present.4 There is a lengthy period in which the two maintained a 1:1 relationship5. The relationship began to change in the early 1980s, with world trade increasing at a much faster rate than world product. The Asian crisis, the dot.com collapse and the massive failure of financial management in 2006 provided a series of challenges which initially appeared to be accommodated without disrupting the growth of world trade.

The growth of world trade was a symptom; the cause was a mixture of real, external factors and a belief which persisted for a generation and beyond in the financial industries that credit was uncapped. The key drivers included the following eight factors:

1. Steady or falling (in real terms) commodity and energy prices which drove up consumption.

2. The doubling of the global work force, and the much more than doubling of their intellectual capacity through education and training, which led in its turn to mobility of labour to where it could be used effectively.

3. Near universal productivity growth was based on the use of increasingly cheap information technology. Between 1960 and 1999, manufacturing’s share in US GDP and total employment both halved, to about 15%. Over the same period, its physical output increased 2-3 times and prices decreased in real terms by 75%.6

4. Labour costs for low-skilled workers in the industrial world were nearly static in real terms.

5. Connectivity and new institutions offered access to the global work force and to world savings.

6. The end of the Cold War led to the apparent supremacy of the Western model of governance. There was near universal and immediate economic response to a standard economic model that comprised sound finance, unimpeded market forces, rational and predictable regulation and taxation, open borders to trade in manufactured goods, all making up the so-called International Monetary Fund (IMF) model.

7. There was a wave of privatisation and deregulation in the industrial world. This spread to the former Comecon countries in Eastern Europe, and in China and India.

8. Finally, financial deregulation had a series of important impacts, as discussed below.

The immediate responses to this growth of world trade were the extension of consumerism in the West and the beginnings of fast growth and liberalisation in the developing economies, most notably in Asia and the ex-Comecon countries in Eastern Europe.

The response of the financial sector was that the world had found a way to manage complexity-through bottom-up choice in markets and democracy, all integrated by sound governance - and that things would find their own equilibrium through benign neglect.

This model has much to commend it. However, ‘benign’ is a word laden with values: whose benignity? For whose advantage? In the short term it suited US and other political leaders to allow central banks to maintain historically low real interest rates, to permit a housing boom that went off the scale, with consumers taking on a vast burden of debt.

Asian savings funded some of this expansion, while demographics in the wealthy world meant that many had accumulated savings and pension funds that needed to be invested. A glut of capital forced down price/earnings ratios on securities. Increasing shareholder activism was driven by this and other factors, such as the boom in mergers and hostile acquisitions, and consumerism applied to securities markets expanded by low trading costs. Companies could not compete with the high returns from the financial sector and were squeezed for cash for organic investment. Boards were ejected by shareholders if they were not content with the company’s performance.

The role of the financial sector

The financial sector had been hugely important in the early twentieth-century stock markets, but had since declined to a small share of the market. Retail banking was famously parodied in Liar’s Poker as 3/6/3: borrow at 3%, lend at 6%, be on the golf course at 3pm. Merchant banks did esoteric things on a small scale and had no great significance. Few banks engaged in asset trading, in the sense of playing zero-sum games with other people’s money.

Changing regulation

In the early 1990s, banks discovered the joys of corporate finance and expanded rapidly into new areas. This was accelerated by the repeal of the depression-era US Glass-Steagall Act in 1999. This had separated commercial from investment banking, and its repeal opened the door to new monolithic firms.

All manner of new products were on offer. Mergers and acquisitions were studied and actively promoted to corporate chieftains with ready finance. Methods of borrowing to please shareholders with a short time horizon - such as to buy back shares, or to pay dividends - were parts of the package. The chief offer that had unambiguous positive sum value associated with it was, however, the wide range of packages that claimed to manage risk exposure.

Hedging of risk

Portfolios that are constructed from many unrelated risks that are small in comparison to the total are proportionately less exposed to volatility than the constituent components. That is how insurance works: if your house burns down, that is a catastrophe for you, but it is not such a proportional disaster for an insurance company that holds tens of thousands of such risks. You are, therefore, happy to pay a small sum to remove the financial - if not practical - risk; and the company can accept it knowing that the likelihood of all of the houses that it insures burning down in the same time period is very low.

It is, however, a crucial caveat for insurance that the risks must be ‘uncorrelated’, must not respond to a common precipitating factor, such as war.

Offers claiming to manage risk exposure allowed companies to ‘hedge’ risk; buying what was sold as insurance against currency movements, inflation, commodity price changes and supply chain defaults. This was a powerful gain and the corporate treasury function became closely linked to - or outsourced to - banks.

Borrowing

This closeness also encouraged borrowing on a vast scale, often for financial transactions - such as acquisitions - rather than for investment in plant and equipment. The new monoliths sent teams of people to visit corporate CEOs in order to suggest projects that they would then finance: acquire this, strip out that - it seemed that you could create hundreds of millions of dollars out of absolutely nothing.

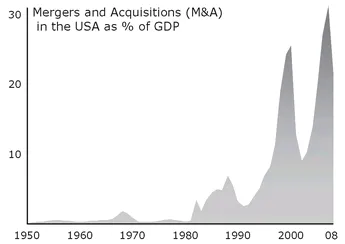

Figure 1.2 shows the mergers and acquisitions value in the USA as a percentage of the GDP.7 It emphasises the amazingly large peaks of activity in the decade 2000-2008.

Own-account trading by banks and CDOs

Banks found another interesting area: own-account trading. That is, they could use their current assets to borrow, and use that money to speculate in markets. At first controlled by regulatory limits, this soon went ‘off the balance sheet’, being handled by entities to which the regulatory control did not apply. More and more complex instruments were devised, including the now-notorious collateralised debt obligations, or CDOs. As they illustrate the abstract nature of what was being done, these are worth a general description.

Figure 1.2 Mergers and acquisitions as a percentage of US GDP

A bank creates a new legal entity, usually called an SPE or special purpose entity. It places a collection of assets into this, which are divided into various classes of risk exposure, here meaning chiefly proneness to volatility. Each CDO or group of assets has a class.

Ratings agencies validated these structures, and had to compete against each other for the privilege. Over-strict assessors were less likely to be selected, all things being equal.

CDOs were purchased by other institutions. The high-risk ones offered a high return, and low-risk ones provided supposedly quality assets against which further money could be borrowed, so repeating the cycle. This is called ‘securitisation’, and allowed banks to take on dizzy levels of debt that was certified to be triple-A. As we have now seen, they in practice often contained toxic assets or assets which all moved in the same direction when times got hard.

Some figures may serve to put this in context:8

Table 1.1 World values

| World added value, 2007 approximately | $35 trillion |

| World value of equities, 2007 | $40 trillion |

| World value of derivatives, inc. CDOs | $1000 trillion |

| World values of credit default swaps | $70-90 trillion |

Boom and bust in financial services

The upshot was that the banking sector boomed, paid out very high salaries and bonuses, and lost control of its fundamentals. Senior staff had very little idea what their subordinates were doing, as the instruments were technical and changed very rapidly. Accounting structures that worked on a mark-to-market basis - that is, booked (marked) assets at what they were worth ‘in the market’ at the moment of booking - had to work within an extremely ill-defined framework: what, ultimately, was the market value of a derivative built on a dozen CDOs that were themselves spires above huge, mixed bunches of assets that included the now notorious sub-prime property...