![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Down on the Farm . . .

The simple principle of life is to find out what she wants and give it to her. It’s worked in my marriage for 35 years and it works in laundry.1

—A.G. Lafley, CEO, Procter & Gamble

WHY RETAIL IS LIKE FARMING

My neighbour, Tim Smith, was actually a farmer before he became my neighbour. Tim is a real character, with a devilish sense of humour and a wonderfully balanced world view about farming. He explains to us novices that conventional agriculture is about cultivating a space and achieving the best yield possible in that space. It takes advantage of the “economies of scale” principle. However, Tim goes on to point out that, over the last 10 years, farmers have finally realized that monoculture has become a big problem. A monoculture is a single crop that is harvested, processed, and marketed without differentiation.

The Perils of Retail Monoculture

Our guy Sean, a lifelong retail man, maintains that today’s retail environment is actually the business equivalent of monoculture. “Retailers tend to broad-brush their consumer base with the same brush, with inadequate recognition of diversity. Everyone is sold the same stuff the same way. Those companies that do decide to differentiate women often fall prey to what we call pink-washing, which are strategies that invariably lack depth, substance, variety, or authenticity.”

By retail monoculture, we are specifically referring to retail management and a strategic world view that employs only a narrow vision. Monoculture is evident in company head offices where a MAWG (middle-aged white guy) syndrome can flourish. Therefore, the filter used can be pretty one-dimensional. We’ll speak about this in Chapter 4, but think beer and car companies, the investment business, and, believe it or not, even certain cosmetics companies. (It’s not always the traditional “male bastions.”)

While the upside of retail monoculture is clear—economic efficiencies, knowing your market extremely well, etc.—there are very serious downsides to monoculture, whether your product is potatoes or pantyhose.

“Retailers,” Sean explains, “exhibit a strong focus on supply chain management and lower prices. This means more and more companies are finding themselves having to constantly ‘fertilize’ in order to stay relevant. More resources are needed just to keep up current levels of production. Not only does this take a significant toll on a company’s ability to stay viable, the strategies generally used to maximize yield almost always fail women consumers. This includes things like the old tried-and-true ‘stack ’em high and watch ’em fly’ mantra, as well as offering products and services in a good-better-best hierarchy. There is a famous marketing mantra: ‘People buy solutions, not products.’ Women in particular seek solutions that this good-better-best product hierarchy will not address. It doesn’t look at a product lineup holistically and if you see your product only in a hierarchical framework, often you miss the value and solution that it provides.”

In a nutshell, it looks like this:

A traditional farmer practising monoculture has a very one-dimensional view of the world (and his or her product), and often operates on the premise of perceived short-term efficiency despite the damage done to the environment and missed opportunities to do things better. Retailers who are traditionalists meet the needs of women consumers through a one-dimensional “marketing-to-women” lens, and concentrate on short-term efficiency, missing out on profits and, in the end, damaging shareholder value.

Almost every North American car company is suffering as the result of this type of short-term thinking and the consumer experience for women continues to be below par, yet Japanese companies are kicking butt. The Globe and Mail reported on a study of the relationship between customer satisfaction and stock prices, and found a strong link. The researchers found that between February 18, 1997 and May 21, 2003, a hypothetical portfolio based on American Customer Satisfaction Index (ACSI) data outperformed the Dow Jones Industrial Average by 93 percent and the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index by 201 percent. A second, real-world portfolio also outshone the S&P 500 in each year between 2000 and 2004. Companies that performed well on the stock market were Toyota Motor Corp., Apple Computer Inc., and Google Inc., and were also companies that scored high on the ACSI. Companies like Ford Motor Co. scored at the low end of the scale.

An organic farmer looks at everything holistically; no one element of farming is left out of the cycle. It’s also an attitude. A gender-intelligent retailer does the same. Women’s consumer needs and preferences are intrinsic to all parts of the planning and strategy cycle, not just in marketing. Gender intelligence is an attitude as well. But in the corporate world, to make things holistic, we first need to break down the pieces by using a gender-based filter and then put the pieces back together again.

It’s not that the business model necessarily changes, though it can. In the retail and services world, companies need to develop products and services, conduct market research, market, advertise, and sell their goods and services. This doesn’t change when a company creates a gender-intelligent ecosystem. It’s just that these areas now have a gender-conscious lens in their approach to doing everything. And believe me, it’s badly needed.

In the business world, this critically important gender-lens file folder seems to be stuck in the bottom drawer. Women make most of the consumer buying decisions, but even more compelling is that women consumers, much more so than men, are incredibly attuned to the micro-level detail of the entire consumer process. This is a process that starts from a comment made by a friend, the first phone call or the first visit to the company’s website, and runs straight through to after-sales customer service and the company’s presence in the community. According to our research, women could tell if a company understood their needs by the way a salesperson talked to them. These highly developed consumer antennae can create a great deal of pressure on an unsuspecting company.

INCENTIVE TO MAINTAINING THE STATUS QUO IN RETAIL

Retailers are locked to the status quo. Much of what you see as a consumer at the store level is the result of buying decisions made up to 18 months before and, in some instances, designed and developed two to three years earlier. What lives in the store/office today is often a retailer’s or service provider’s best guess at what the landscape will look like months to years out. Not surprisingly, they are committed to this inventory or service because they now “own” it.

This can result in an organization becoming resistant to change. Even if you want to change your product, the reality of the global supply chain makes it tough. Suppliers have plenty on the line because they make a sizable investment in building product a certain way. However, Graeme Spicer, a Toronto-based retail strategist with years of experience tucked under his belt working with giants like Wal-Mart and Bata Retail, explains from his perspective that change may be in the wind. “Retailers are waking up to the concept of ‘speed to market’ resulting in increasingly compressed product development cycles and leaner inventory.”

Retailers and service folk have a lot committed in their physical store/office layouts. In a retail store, shelving is expensive. The retail world also has very little downtime to get things done. Any retailer of any significant size is stocking through the night. It’s a business that is essentially running 24/7 to meet consumer needs. If you have to make any changes, it’s difficult to do so without interrupting the business. This can make the whole enterprise, both management and store employees, cranky because it can have a rather negative effect on revenues.

By no means are we minimizing or dismissing these very real issues. But the fact remains that the traditional retail practice of selling in the same way to everyone without taking into account the diversity of consumers and, in particular, women, who make most of the consumer decisions, simply doesn’t work. The conventional marketing-to-women approach flourishes because it doesn’t require a major shift in the organization. This business model looks at meeting the needs of women as an “event” or something special to do or create, rather than as an integrated business core competency.

Change is a big deal in any organization, but gender intelligence is as much about a way of thinking about problems and business challenges as it is about radically altering your organization. Most of the companies that we profile in this book took on some big changes, but, equally important, they started to think differently. They have started using a gender lens, something that hugely impacts the future.

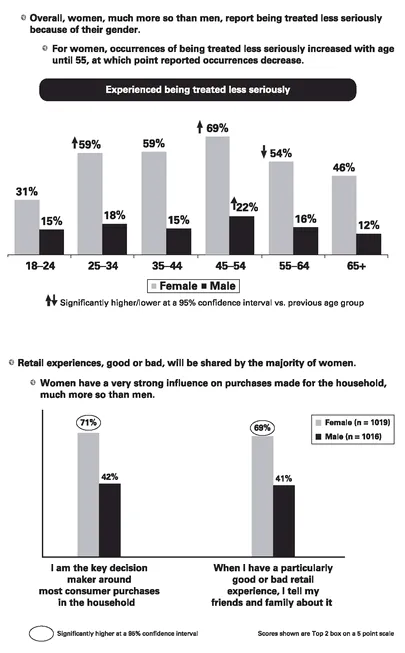

In retail, it’s pretty important to know how your customers are feeling. In a gender-based study that we conducted with Maritz Research in 2007, we asked 1,000 Canadian women and men their world view about the stars and dogs of the retail and services world. This is what we found:

Well over half of the women in our study said they had experienced a retail situation where they felt they were being treated less seriously because of their gender. Almost three times as many women than men made this statement.

But here’s the paradox. Seventy-one percent of the women in our study said they were the key decision maker regarding consumer purchases in the household, with 42 percent of men saying the same thing.

Men don’t tend to say or do much about bad experiences. Forty-one percent of discontented male consumers tell friends and family about a bad experience. If a woman is ticked off, close to 70 percent go on the verbal warpath.

The following chart is one we’ve created from a collection of our own and other academic research that gives you some sense of how gender differences can manifest in consumer behaviour.

CONSUMER-BASED GENDER DIFFERENCES

| WOMEN | MEN |

| What is our decision-making process? | • intuitive | • rational |

| • subjective | • objective |

| • decisions made after each detail is explored | • straight to the point |

| What are their dominant decision criteria? | • relationship with customer point of contact | • the job the salesperson does |

| • prefer mentor rather than adviser |

| How do they view negotiation? | • win-win | • win-lose |

| How do clients want to be closed? | •suggestive | • directive |

| How do we gauge performance? | • quality of advice and relationship, not just performance | • performance relative to others |

| How do we achieve the highest-quality relationships? | • performance plus relationship | • achievement in and of itself |

| How can we continue to motivate relationships? | • inspiration from within | • logic—what can you produce? |

| • women want their salesperson and their friends to succeed, therefore more likely to refer |

| How should you deal with on the problems as they occur? | • want to... |