![]()

CHAPTER ONE

PROJECT CONTROL

Peter Harpum

Project control is about ensuring that the project delivers what it is set up to deliver. Fundamentally, the process of project control deals with ensuring that other project processes are operating properly. It is these other processes that will deliver the project’s products, which in turn will create the change desired by the project’s sponsor. This chapter provides an overview of the project control processes, in order to provide the conceptual framework for the rest of this section of the book.

Introduction

Control is fundamental to all management endeavor. To manage implies that control must be exercised. Peter Checkland connects the two concepts as follows:

The management process. . .is concerned with deciding to do or not to do something, with planning, with alternatives, with monitoring performance, with collaborating with other people or achieving ends through others; it is the process of taking decisions in social systems in the face of problems which may not be self generated.

Checkland, 1981

In short to

• plan

• monitor

• take action

One may ask what is the difference between project control and any other type of management control? Fundamentally there is little that project managers must do to control their work that a line manager does not do. Managers of lines and projects are both concerned with planning work; ensuring it is carried out effectively (the output from the work “does the job”) and efficiently (the work is carried out at minimum effort and cost). Ultimately, managers of lines and projects are concerned with delivering what the customer wants. The line management function is usually focussed on maximizing the efficiency of an existing set of processes—by gradual and incremental change—for as long as the processes are needed. The objective of operations management (or “business-as-usual”) is rarely to create change of significant magnitude. Projects, on the other hand, are trying to reach a predefined end state that is different to the state of affairs currently existing; projects exist to create change. Because of this, projects are almost always time-bound. Hence, the significant difference is not in control per se, but in the processes that are being controlled—and in the focus of that control.

Project management is seen by many people as mechanistic (rigidly follow set processes and controlled by specialist tools, apropos a machine) in its approach. This is unsurprising given that the modern origins of the profession lie in the hard-nosed world of defense industry contracting in America. These defense projects (for example, the Atlas and Polaris missiles) were essentially very large systems engineering programs where it was important to schedule work in the most efficient manner possible. Most of the main scheduling tools had been invented by the mid-1960s. In fact, virtually all the mainstream project control techniques were in use by the late 1960s. A host of other project control tools were all available to the project manager by the 1970s, such as resource management, work breakdown structures, risk management, earned value, quality engineering, configuration management, and systems analysis (Morris, 1997).

The reality, of course, is that project management has another, equally important aspect to it. Since the beginning of the 1970s research has shown that project success is not dependent only on the effective use of these mechanistic tools. Those elements of project management to do with managing people and the project’s environment (leadership, team building, negotiation, motivation, stakeholder management, and others) have been shown to have a huge impact on the success, or otherwise, of projects (Morris, 1987; Pinto and Slevin, 1987—see also Chapter 5 by Brandon. Both these two aspects of project management—“mechanistic” control and “soft,” people-orientated skills—are of equal importance, and this chapter does not set out to put project control in a position of dominance in the project management process. Nevertheless, it is clear that effective control of the resources available to the project manager (time, money, people, equipment) is central to delivering change. This chapter explains why effective control is fundamentally a requirement for project success.

The first part of the chapter explains the concept of control, starting with a brief outline of systems theory and how it is applied in practice to project control. The second part of the chapter outlines the project planning process—before project work can be controlled, it is critical that the work to be carried out is defined. Finally, the chapter brings project planning and control together, describing how variance from the plan is identified using performance measurement techniques.

Project Control and Systems Theory

Underlying control theory in the management sciences is the concept of the system. The way that a project is controlled is fundamentally based on the concept of system control—in this case the system represents the project. Taking a systems approach leads to an understanding of how projects function in the environment in which they exist. A system describes, in a holistic manner, how groups are related to each other. These may, for instance, be groups of people, groups of technical equipment, groups of procedures, and so on. (In fact, the systems approach grew out of general systems theory, which sought to understand the concept of “wholeness”—see Bertalanffy, 1969.) The systems approach exists within the same conceptual framework as a project; namely, to facilitate change from an initial starting position to an identified final position.

The Basic Open System

A closed system is primarily differentiated from an open system in that the former has impermeable boundaries to the environment (what goes on outside the system does not affect the system), while the latter has permeable boundaries (the environment can penetrate the boundary and therefore affect the system). In a closed system, fixed “laws” enable accurate predictions of future events to be made. A typical example of this is in physical systems (say, for instance, a lever) where a known and unchanging equation can be used to predict exactly what the result will be of applying a force to one part of the system. Open systems do not allow such accurate predictions to be made about the future, because many influences cross the boundary and interact with the system, making the creation of predictive laws impossible.

The key feature of the open system approach that makes it useful in the analysis and control of change is that the theory demands a holistic approach be taken to understanding the processes and the context they are embedded in. It ensures that account is taken of all relevant factors, inputs or influences on the system, and its environmental context. Another key feature of an open system is that the boundaries are to a large extent set arbitrarily, depending on the observer’s perspective. Moreover, wherever the boundaries are placed, they are still always permeable to energy and information from the outside. It is this quality that allows the relationships between the system and its environment to be considered in the context of change, from an initial condition to a final one.

A critical part of this theory that is useful when considering management control is that the open system always moves toward the achievement of superordinate goals. This means that although there may be conflicting immediate goals within the creative transformation process(es), the overall system moves toward predefined goals that benefit the system as a whole (see Katz and Kahn, 1969). In a project system these goals are the project objectives.

In simple terms the basic open system model is shown in Figure 1.1.

The Open System Model Applied to Project Control

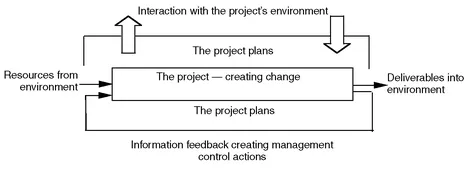

If the generic system diagram is redrawn to represent a project and its environment, the relationship of control to planning (how the project is going to achieve its objectives) can be made clear (see Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.1. THE BASIC SYSTEMS MODEL.

Source: After Jackson (1993).

The value of the open system model of the project shows how the “mechanistic” control meta process attempts to ensure that the project continues toward achievement of its objectives and the overall goal. The “softer” behavioral issues are evident throughout the project system: within the project processes, acting across the permeable boundaries with the project stakeholders and wider environment, and indeed around the “outside” of the project system but nevertheless affecting the project goal—and hence the direction the project needs to move in to reach that goal.

The boundaries of the project are defined by the project plans. These plans define what the project processes need to do to reach the system’s goals (defined by the project’s environment). The plans also determine where in the organizational hierarchy the project exists, because projects have subsystems (work packages) and exist within a supra-system (programs and portfolios of projects). This is shown in Figure 1.3.

FIGURE 1.2. THE PROJECT AS A SYSTEM.

FIGURE 1.3. THE HIERARCHICAL NATURE OF PROJECT CONTROL SYSTEMS.

To make the distinctions clear between portfolio and program, their definitions are listed in the following, elaborated for clarity from the Association for Project Management Body of Knowledge, 4th edition (APM, 2000):

| Program management | Often a series of projects are required to implement strategic change. Controlling a series of projects that are directed toward a related goal is program management. The program seeks to integrate the business strategy, or part of it, and the projects that will implement that strategy in an overarching framework. |

| Portfolio management | In contrast to a program, a portfolio comprises a number of projects, or programs, that are not necessarily linked by common objectives (other than at the highest level), but rather are grouped together to enable better control to be exercised over them. |

The feedback loop measures where the project is deviating from its route (the plans) to achieving the project goals and provides inputs to the system to correct the deviation. Control is therefore central to the project system; it tries to ensure that the project stays on course to meet its objectives and to fulfill ...