- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Adopting a unique approach, this novel textbook integrates science and business for an inside view on the biotech industry. Peering behind the scenes, it provides a thorough analysis of the foundations of the present day industry for students and professionals alike: its history, its tools and processes, its markets and products. The authors, themselves close witnesses of the emergence of modern biotechnology from its very beginnings in the 1980s, clearly separate facts from fiction, looking behind the exaggerated claims made by start-up companies trying to attract investors. Essential reading for every student and junior researcher looking for a career in the biotech sector.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Concepts in Biotechnology by Klaus Buchholz,John Collins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biotechnology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

History

1

Introduction

Historical events in early biotechnology comprise fascinating discoveries, such as yeast and bacteria as living matter being responsible for the fermentation of beer and wine. The art of Biotechnology emerged from agriculture and animal husbandry in ancient times through the empirical use of plants and animals which could be used as food or dyes, particularly where they had been preserved by natural processes and fermentations. Improvements were mostly handed on by word of mouth, and groups that maintained these improvements had a better chance of survival during periods of famine and drought. In such processes alcohol was produced and provided highly acceptable drinks such as beer and wine, or acids were formed which acted as the preservative agent in the storable food produced.

In this book we follow how the study of the chemical nature of the components involved in biotechnology first became possible subsequent to the development of chemistry and physics. Serious controversies about the theories both vitalist and chemical, resulted in the reversal of theories and paradigms; significant interaction with and stimulus from the arts and industries prompted the continuing research and progress. Last but not least, it was accepted that the products produced by living organisms should not be treated differently from inorganic materials. Pasteur’s work led to the abandonment of the idea which had been an anathema to exact scientific enquiry in the life sciences, namely ‘spontaneous generation’. He established the science of microbiology by developing pure monoculture in sterile medium, and together with the work of Robert Koch the experimental criteria required to show that a pathogenic organism is the causative agent for a disease were also recognised. Several decades later Buchner disproved the hypothesis that processes in living cells required a metaphysical ‘vis vitalis’ in addition to what was necessary to understand general chemistry. Enzymes were shown to be the chemical basis of bioconversions. Biochemistry emerged as a new speciality prompting dynamic research in enzymatic and metabolic reactions. However, the structure of proteins was not established until more than 40 years later.

The requirements for antibiotics and vaccines to combat disease, and chemical components required for explosives particularly in war time, stimulated exact studies in producing products from microbial fermentations. By the mid-twentieth century, Biotechnology was becoming an accepted speciality with courses being established in the life sciences departments of several Universities.

Basic research in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology dramatically widened the field of life sciences and at the same time unified them considerably by the study of genes and their relatedness throughout the evolutionary process. The scope of accessible products and services expanded significantly. Economic input accelerated research and development, by encouraging and financing the development of new methods, tools, machines, and robots. The discipline of ‘New Biotechnology’, one of the lead sciences which resulted from an intimate association between business and science, is still the subject of critical public appraisal in many Western countries due to a particular lack of confidence in the notion that improved quality of life will prevail in spite of commercial interest.

The study of the history of science, and specifically that of Biotechnology, should go beyond documenting and recording events and should ideally contribute to an understanding of the motives and mechanisms governing the dynamics of sciences; the role of inquisitiveness in gaining new knowledge and insights into nature, of reputation-building, of the interplay between economics and business; the role of and dependance on theories, the role of analytical and experimental, as well mathematical methods, and more recently computation and robotics.

In the first part of this book the emphasis is on scientific discoveries and results, theories, technical development, the creation of leading paradigms, and on their decay. Industrial problems and political issues, and their influence on and correlation with developments in science are also addressed.

Although biotechnology has historical roots, it continues to influence diverse industrial fields of activity, including food and feed and commodities, for example polymer manufacture, providing services such as environmental protection, biofuel and energy including biofuel cells, and the development and production of many of the most effective drugs.

2

The Early Period to 1850

2.1 Introduction

Fermentation has been of great practical and economic relevance as an art and handicraft for thousands of years, yet, in the absence of analytical tools, there was initially no understanding of the changes in constituents that took place. There were serious controversies regarding the vitalistic or chemical nature of these processes. The vitalists believed that mysterious events and forces would be involved such as spontaneous generation of life and a specific vital force, while the chemical school, with Liebig at its head, was in contrast, convinced that only chemical decay processes took place, denying that any living organism was involved in fermentation. Nevertheless most of the phenomena that are relevant to the understanding of the role of microorganisms were noted. It was only during the following period, from 1855 onwards, that Pasteur proposed a theory of fermentation which discredited the hypothesis of spontaneous generation as well as that of Liebig and his school.

‘Natural’ processes would have been identified and adopted by human populations as soon as food hoarding became of interest. Water-tight vessels, such as pots and animal skins would have aided these processes as compared to drying, salting and smoking. This would have allowed the spontaneous discovery of processes for making beer, wines, yoghurt, and sauerkraut from fruit juices, milk, and vegetables. ‘Natural’ fermentations would have been discovered spontaneously but have only been documented in more recent history, although such practices presumably predate writing by many thousands of years.

Barley, which is the basic raw material for beer preparation but not for bread making, was the first cereal to be cultured about 12 500 years BP (= before present), and was grown 6000 years before bread became a staple food; the first document on food preparation was written by the Sumerians 6000 years ago and describes the technique of brewing. A new theory by Reichholf [1] claims that mankind formed settlements after the discovery of fermentation and used the alcohol produced by this process for indoctrination into a cult or for purposes of worship [1, p. 265–269, 259–264].1) Thus beer and wine manufacture form the roots of Biotechnology practices which were developed in ancient times. The vine is assumed to originate from the Black and Caspian seas, and to have been cultivated in India, Egypt and Israel during this early period. In Greek mythology gods such as Dionysos or Bacchus, granted the availability of wine (Figure 2.1) and the birthplace of Dionysos is believed to have been in the Indian mountain Nysa (Hindukusch) [2, p. 441], [3, p. 591–595], [4, Vol. 12, p. 1, 2].

Figure 2.1 Olympus, Nectar Time (Dionysos: god’s thunder – the miracle of wine formation) [5].

Written documentation on beer and wine manufacture which form the roots of Biotechnology can be traced back in ancient history: about 3500 BC brewers in Mesopotamia manufactured beer following established recipes [6]. In 3960 BP King Osiris of Egypt is assumed to have introduced the production of beer from malted cereals [7,p. 1001]. In Asia, fermentation of alcoholic beverages has been documented since 4000 BP, and fermentation starters2) are estimated to have been produced about 6000 BP by the daughter of the legendary king of Woo, known as the Goddess of rice- wine in Chinese culture [8, p. 38, 39,45]. Soya fermentation was established in China around 3500 BP. Around about 2400 BP, Homer described in The Iliad the coagulation of milk using the juice produced from figs which contains proteases. Pozol, a nonalcoholic fermented beverage, dates back to the Maya culture in Yucatan, Mexico [9]. There is a mythical report that Quetzalcoatl, a Toltec king of the tenth century, was seduced by demons to drink wine with his servants and his sister so that they became drunk and addicted to desire and pleasure; later Quetzalcoatl set fire to himself as an act of repentance and was resurrected as a king on another planet [10].

Tacitus reports that the Germans have a history of beer-making [11, p. 299]. The famous German law of 1516 on brewing has its origins in Bavaria. The medieval tradition of brewing can be traced back through the literature, such as the first books by the ‘Doctor beider Rechte’ Johannes Faust, who wrote five books on the ‘divine and noble art of brewing [12, Vol. 2, p. 409, 410].

Thus in the absence of detailed knowledge of the process, fermentation became a rational method of utilizing living systems. The fermentation of tobacco and tea were also established in ancient times. These fermentations were presumably initially adopted as fortuitous processes. In fact all of them utilize living systems, however, the early users of fermentation had no understanding of neither the origins of the essential organisms involved nor their identities nor the way in which they predominated over possible contaminants. A most significant step was the description of tiny ‘animalcules’ in drops of liquids, which Leeuwenhook observed with his microscope (about 1680, the year in which he became a member of the Royal Society in London). This, however, was not seen in the context of, or correlated to fermentation. Stahl in his 1697 book Zymotechnika Fundamentals (the Greek ‘zyme’, meaning yeast) explored the nature of fermentation as an important industrial process, where by zymotechnica was used as a descriptor for the scientific study of such processes [13].

Various descriptions were associated with ‘bad air’ in marshy districts. In 1776 A. Volta observed the formation of ‘combustible air’ (methane, ‘hidrogenium carbonatrum’, as analysed by Lavoisier in 1787) from sediments and marshy places in lake Lago Maggiore in Italy. He noted that ‘This air burns with a beautiful blue flame…’ [14]. The first enzymatic reactions, then considered to be fermentative in nature, were observed by the end of the eighteenth century. Thus the liquefaction of meat by the gastric juices was noted by Spallanzani as early as 1783 [15], the enzymatic hydrolysis of tannin was described by Scheele in 1786 [16], and Irvine detected starch hydrolysis in the aqueous extract of germinating barley in 1785 [17, p. 5]. Such processes or reactions were distinguished from simple ‘inorganic’ reactions on the basis that the reaction could be stopped by heat denaturation of the ‘organic’ components.

In addition to providing pleasure, beer and wine manufacture have become economically important because for several thousand years dating back to the early economy of Mesopotamia and Egypt, it has been a major source of tax revenue. The manufacture of alcoholic beverages developed into major industrial activities during the nineteenth century, and further fermentation processes were embraced enthusiastically in order to widen the horizon for new business opportunities, the expression of which was the foundation of numerous research institutes in several European countries during the nineteenth century.

2.2 Experimental Scientific Findings

2.2.1 Alcoholic Fermentation

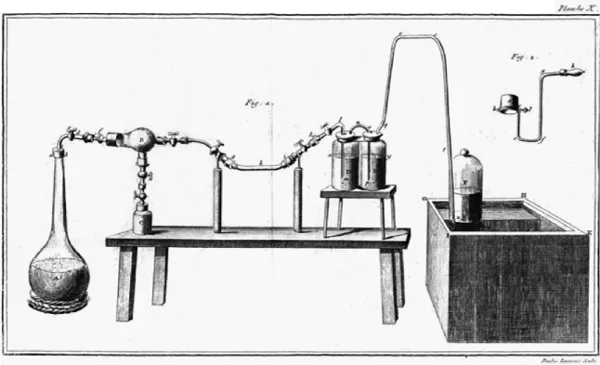

Due to its great practical relevance alcoholic fermentation was the focus of technical as well as scientific interest. The essential results are reported here and also include the early findings on acetic acid fermentation. In the second half of the eighteenth century Spallanzani had undertaken microscopic investigations on microbial growth. He showed that microorganisms do not arise spontaneously [18, p. 14], [19, p. 112]. A key event was the development of the scientific foundation of modern chemistry (as opposed to alchemy) by Lavoisier [20]. He established quantitative correlations and mass balances, based on exact experimentation supporting the idea that specific compounds contained specific compositions and proportions of atoms (see Figure 2.2 for the experimental set up). Lavoisier simply accepted the existence of the ferment and restricted his work to the chemistry of the reaction which occurred during alcoholic fermentation, showing that the only products were ethanol and carbon dioxide. In his famous book of 1793 he gave a phenomenological description of fermentation. Concluding on the products he stated that ‘…when the fermentation is complete the solution does not contain any more sugar….’. ‘So I can say: juice = carbon dioxide + alkool’ [20, p. 141]. In 1810 Gay-Lussac gave the quantitative correlation, with glucose being converted into two moles of ethanol and two of carbon dioxide [17, p.5].

Figure 2.2 Lavoisier’s apparatus for the investigation of fermentation. In the first vessel A the material to be fermented, for example sugar, and beer yeast is added to water of a weight determined exactly; the foam formed during fermentation is collected in the following two vessels B and C; the glass tube h holds a salt, for example nitrate, or potassium acetate; this is followed by two bottles (D, E) containing an alkaline solution which absorbs carbon dioxide, and only air is collected in the last bottle F. This device allowed determination ‘with high precision’ of the weight of the substances undergoing fermentation and formed by the reaction. [20, p. 139, 140, Planche X].

From the end of the eighteenth century efforts to find a solution to the fermentation problem bear witness to the attempt to approach and explain this phenomenon either as the result of the activity of living organisms or as purely interactions of chemical compounds. However from the mid-1830s evidence began to accumulate to indicate that biological aspects formed the basis of fermentation [21, p. 24].

Important findings based on well-designed experiments were published by Schwann and Cagniard-Latour in 1837 and 1838. They showed independently that yeast is a microorganism, an ‘organized’ body, and that alcoholic fermentation is linked to living yeast. In 1838 Cagniard-Latour reported that ‘In the year VIII (1799–1800) the class of physical and mathematical sciences of the Institute (Institut de France) had proposed for the subject (of fermentation) a prize (for solving) the following question: ‘What are the characters in vegetable and animal matter….’ ‘I have undertaken a series of investigations but proceeding otherwise than had been done. That is by studying the phenomena of this activity by the aid of a microscope. … This attempt … was useful since it has supplied several new observations with the following principal results: 1. That the yeast of beer (this ferment of which one makes so much use and which for this reason was suitable for examination in a particular manner) is a mass of little globular bodies able to reproduce themselves, consequently organized, and not a substance simply organic or chemical, as one supposed. 2. That these bodies appear to belong to the vegetable kingdom and to regenerate themselves into two different ways. 3. That they seem to act on a solution of sugar only as long as they are living. From which one can conclude that it is very probably by some effect of their vegetable nature that they disengage carbonic acid from this solution and convert it into spirituous liquor…. I will add that the question formerly proposed by the Institut appears now to be solved… I have communicated (the results) to the Philomatic Society during the years 1835 and 1836.’ [22].

Schwann [23] first reported his experiments concerning spontaneous generation to the Annual Assembly of the Society of German naturalists and Physicians, held in Jena in September 1836. He demonstrated that provided the air was heated neither mould nor infusoria appeared in an infusion of meat and that the organic material did not decompose and become putrid. Schwann perceived that these experiments did not support those of the proponents of spontaneous generation. They could be explained on the basis that air normally contained germs (Keime). Schwann concluded that alcoholic fermentation was promoted by proliferating yeast organisms which he classified as sugar fungi, derived from ‘Zuckerpil...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Series

- Title Page

- Authors

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Abbreviations and Glossary

- Part One History

- Part Two The New Paradigm Based on Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Part Three Application

- Index