![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

BONNIE S. LeROY, PATRICIA McCARTHY VEACH, and DIANNE M. BARTELS

No one cares what you know until they know that you care.

—Danish (2009)

Genetic counseling is at an exciting point in its professional evolution. The explosion of knowledge and multiple opportunities for patients to learn about their genetic risks have far outpaced advances in understanding the complex psychosocial aspects of genetic counseling practice. Although it is the rare genetic counselor who would endorse ''information provision'' as the only role for practitioners, the “counseling” aspects are sometimes eclipsed by the volume of genetic information and technological options. Indeed, 40 years after the first students were accepted into a graduate program designed specifically to train genetic counseling professionals, only a handful of books exist that offer detailed instruction in psychosocial methods for genetic counseling practice.

The contents of this book reflect our fervent belief that the role of genetic counselors extends well beyond that of information provider. Indeed, genetic counselors are active and compassionate participants in patients' efforts to understand their genetic risks, endure their emotional struggles, and make life- altering decisions. Therefore, the following chapters focus either on specific strategies for responding to challenging psychosocial issues of practice or on strategies for promoting genetic counselors' professional development. The authors, who are all recognized experts in genetic counseling theory, practice, and research, provide relevant examples from their professional experiences to illustrate key concepts. They also cite the growing data-based literature in order to provide an empirical foundation for their chapters. They also include experiential activities to help readers personally engage with the major concepts and skills.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE BOOK

The concept of an ''advanced skills'' book grew out of our ongoing discussions of various challenges in practice. We found ourselves repeatedly coming to the conclusion that there is a need for more literature that speaks ''in depth'' about these issues from the perspectives of genetic counselor practitioners and/or researchers who study genetic counseling. In selecting topics for this book, we struggled with the question of what constitutes an advanced skill. When writing our first book (Facilitating the Genetic Counseling Process: A Manual for Practice; McCarthy Veach et al., 2003), we had the benefit of reviewing the 1996 American Board of Genetic Counseling (ABGC) practice-based competencies. The ABGC competencies describe requisite minimal skill levels for entry-level genetic counselors. Advanced skills are another matter: They should represent more complex ways of understanding and implementing concepts.

Once we determined that the chapters should examine key concepts in more complex ways, the question became: ''Which concepts should we include?'' We decided to select topics that represent genetic counseling process; we focused on skills that promote desired genetic counseling outcomes. The chapters address universal and enduring concepts that are relevant across different genetic counseling specialties and patient conditions.

The chapters reflect three major domains: genetic counseling dynamics (Chapters 2 to 8), patient cultural and individual differences (Chapters 9 to 12), and genetic counselor development (Chapters 13 to 15). We invited authors to write their chapters in ways that would enhance genetic counseling professionals' ability to gather relevant information effectively, interpret information to patients, and provide patients with appropriate resources. The chapters go one step further. They suggest ways that genetic counselors can deeply understand patient situations, incorporate patient values into clinical practice, provide in-depth support, and deal with both manifest and latent factors affecting patient decision making. Across these chapters readers will find a wealth of theoretical and empirical descriptions of numerous concepts, relevant clinical examples, and practitioner methods and strategies. A recurrent theme concerns ''the person of the genetic counselor'' vis-a-vis reflective practice and commitment to one's professional growth and development.

Around the time that we were finalizing the prospectus for this book, we were also articulating the reciprocal-engagement model (REM) of genetic counseling practice (McCarthy Veach et al., 2007). Since the REM model undoubtedly influenced our choice of topics, we describe it briefly next.

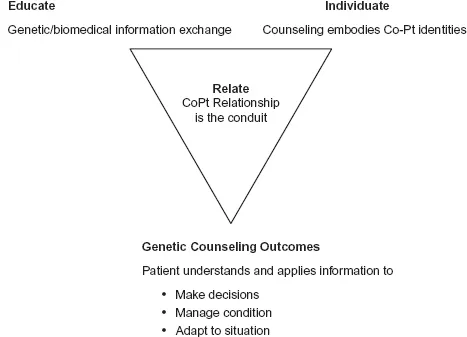

Reciprocal-Engagement Model

The REM model is an amalgamation of data generated during a consensus meeting of North American genetic counseling program directors and our own professional experiences and reflections. In 2004, 23 program directors or their representatives from 20 genetic counseling programs in North America convened for 1% days. Their task was to define a model of genetic counseling practice that is being taught currently. A model of practice ''refers to why and how the service is delivered to patients, as described by tenets, goals, strategies, and behaviors'' (McCarthy Veach et al., 2007, p. 714). The participants worked to develop by consensus the tenets (fundamental beliefs shared by genetic counselors), goals (the aims of genetic counselor practice), strategies (methods for achieving goals), and behaviors (specific actions/interventions) that characterize genetic counseling practice. They identified five tenets.

1. Genetic information is key. Providing information about ''perceived or known genetic contributions to disease'' (p. 721) and engaging in discussion with patients about this information is a particularly unique aspect of genetic counseling.

2. Relationship is integral to genetic counseling. The quality of the relationship developed between the genetic counselor and patient is as important as genetic information. Genetic counseling ''is a relationally-based helping activity whose outcomes are only as good as the connection established between the counselor and patient'' (p. 721).

3. Patient autonomy must be supported. Patients should be as self-directed as possible regarding genetic counseling decisions. The counselor is an active participant, working with the patient's individual characteristics and family and cultural context to facilitate informed decisions. However, an essential aspect of this tenet is that ''the patient knows best'' (p. 721).

4. Patients are resilient. Most patients have the strength to deal with painful situations. Genetic counselors therefore, encourage patients to draw upon their inner resources (coping strategies) and support systems and resources to make decisions and arrive at an acceptance of their situation.

5. Patient emotions make a difference. Patients experience a multitude of emotions that are relevant to genetic counseling. ''Patient emotions interact with all aspects of genetic counseling processes and outcomes, for instance, affecting their desire for information, their comprehension of information, the impact of information on their decisions, their willingness and ability to connect with the counselor, their desire for autonomy, and their perceived resilience'' (p. 722).

These five tenets are illustrated in a triangle that represents their mutual influence on each other (see Figure 1). The genetic counselor-patient relationship is in the center of the triangle because it comprises the conduit for the processes and outcomes of genetic counseling.

The chapters in this book correspond well to the REM. They provide readers with a deeper consideration of patient and counselor characteristics, genetic counseling relationship dynamics, and elements of information provision. Also congruent with the REM, the final chapter of the book addresses professional development and the necessity for genetic counselors to engage in lifelong reflective practice. Reflection is essential for facilitating professional development and for evaluating the impact of one's service provision.

Chapter Descriptions

Resta (Chapter 2: Complicated Shadows: A Critique of Autonomy in Genetic Counseling) presents provocative questions about genetic counselors' emphasis on patient autonomy as the primary underpinning of genetic counseling practice. He describes situations in which patient autonomy is not the central tenet. He questions whether autonomy should be the central tenet in many situations. Resta's perspective is consistent with the REM view of autonomy as one of five tenets, as opposed to its being the single central belief.

Zanko and Fox (Chapter 3: Actively Engaging with Patients in Decision Making) argue that the genetic counselor role has become bolder. Genetic counselors must be actively involved in patient decision making. They are an integral part of the process, as opposed to being observers or bystanders. Genetic counselors should evaluate patients' decision-making processes and actively critique those processes. As such, genetic counselors are responsible in part for their patients' decisions. The authors note that ''the genetic counselor accepts direct responsibility for facilitating a decision that will alter the quality of the patient's life.'' Zanko and Fox illustrate the genetic counselor's collaborative role as described in the REM as well as the importance of genetic counselors actively participating in patients' decisions.

DeLany Dixon and Konheim-Kalkstein (Chapter 4: Risk Communication: A Complex Process) describe how risk assessment and risk communication are at best imprecise, ambiguous, unpredictable activities. Furthermore, ''risk'' is understood by everyone, but not in the same way, and it certainly is not dealt with by everyone in the same way. Preparation as a scientist makes us prone to believing that we have hard, clear facts and that it is those facts primarily that patients seek from us. Although genetic information certainly is a main course in counseling sessions, DeLany Dixon and Konheim-Kalkstein point out that helping patients deal with and understand the numbers may not be as important as helping them deal with the pain of uncertainty and the burden of decision outcomes. Their views are reflected in the REM tenet that acknowledges the importance of patients' emotions as well as their resilience in the face of painful situations and decisions. Their perspective further reflects a key theme of the REM: that counselor empathy is an essential component of the genetic counseling process.

Gettig (Chapter 5: Grieving: An Inevitable Journey), Baty (Chapter 6: Facing Patient Anger), and Weil (Chapters 7: Resistance and Adherence: Understanding the Patient's Perspective, and Chapter 8: Countertransference: Making the Unconscious Conscious) offer rich perspectives on common genetic counseling dynamics, including influences of patients and counselors' past interpersonal histories on the genetic counseling relationship and the role of patient and genetic counselor affective states. Weil tells us that some degree of resistance is inevitable and that it reflects, in part, a healthy attempt by patients to cope with their difficult situations. Thus, resistance is a form of resilience (as described in the REM model). Genetic counselors also experience resistance and they need to recognize this tendency in themselves and work on ways to manage it. In a second chapter, Weil describes countertransference and discusses how it is an inevitable dynamic, one that parallels patient transference. To a certain extent, everything that a genetic counselor does in the moment is a reflection of past relationships and experiences (i.e., countertransference). Unexamined counter- transference can have negative ramifications. In contrast, when genetic counselors work actively to recognize and manage their countertransference, they are better able to serve each patient's best interests. Weil provides many useful strategies to assist genetic counselors in recognizing and addressing resistance and countertransference.

Grief and anger are perhaps two of the most socially distressing emotions for many people. Genetic counselors are not immune to their impact (cf. McCarthy Veach et al., 2001). One possible response to intense emotions is to pretend that they don't exist. Gettig cautions against pretending that patients are not grieving, and she reminds us that genetic counseling goals do not include helping patients ''get over'' their grief. Grief is a legitimate part of one's decision making and coping-adaptation. Gettig further emphasizes that contrary to what one might think, patients are the experts when it comes to their grief experience. Therefore, although it can be very useful to draw from one's own life experience and prior clinical experiences, genetic counselors must listen to their patients' unique stories. Baty similarly recommends that genetic counselors acknowledge and address patient anger. She advises genetic counselors to make efforts not to take patients' anger personally: rather, to understand that anger is part of the process. Baty further offers a number of strategies for responding effectively to patient anger.

Lewis (Chapter 9: Honoring Diversity: Cultural Competence in Genetic Counseling) tells us that cultural competence requires continual self-reflection by genetic counselors in order to build awareness of personal biases. Cultural competence also requires counselors to increase their knowledge of and sensitivity toward patients' cultural differences and how these differences interact with patients' individual characteristics. He notes: “Helping patients come to terms with the presenting condition, within the context of their own lives, is the goal [of culturally competent genetic counseling].'' He also says: ''One challenge to cultural competence and to the psychosocial dimension of genetic counseling is the proliferation of new technologies and the focus on their rapid deployment across the field . . . . As a field, we must reiterate the importance of listening 'with' the patient in the counseling moment and developing a perspective that honors the cultural and non-cultural narratives that the patient brings to the genetic counseling encounter.''

Eunpu (Chapter 10: Genetic Counseling Strategies for Working with Families) and Austin (Chapter 11: Developmentally Based Approaches for Counseling Children and Adolescents), in their respective chapters, describe useful strategies for working with families, children, and adolescents. Eunpu illustrates common dynamics in family systems, while Austin provides devel- opmentally appropriate counseling techniques. These authors also remind us that genetic counseling always means ''families,'' regardless of who attends a genetic counseling session. If genetic counselors focus too intensely on a goal of helping individuals make decisions that are ''best for them,'' they may overlook the reality that most patients are influenced by and do consider other family members. Thus, it is not possible to make a completely independent decision.

Finucane (Chapter 12: Genetic Counseling for Women with Intellectual Disabilities) illustrates an important individual difference in her focus on genetic counseling for women with limited cognitive capacities. Cognitive variability affects how patients participate in genetic counseling, and Finucane discusses ways in which genetic counselors might modify their approaches accordingly. Similar to Austin, Finucane provides developmentally appropriate strategies.

Resta, Zanko and Fox, DeLany Dixon and Konheim-Kalkstein, Gettig, Baty, Weil, Lewis, Eunpu, Austin, and Finucane provide a common message: Although genetic counselors have a rich clinical basis on which to understand and approach each patient, they must balance their clinical wisdom against the reality that they know ''nothing'' about a particular patient. Only by carefully listening to the patient sitting in front of them and taking care to build a strong relationship can genetic counselors more fully support the patient's unique situation. They further emphasize the importance of being aware of and, in many cases, bringing out into the open more latent aspects of genetic counseling interactions (feelings, perceptions, biases, values) that play such a strong role in both processes and outcomes.

The remaining chapters of this book speak to some of the ways that genetic counselors can build and maintain their ability to listen and relate in unique ways to each patient. These chapters focus on genetic counselor professional development, reflective practice, and self-care—all play central roles in one's service provision.

Peters (Chapter 13: Genetic Counselors: Caring Mindfully for Ourselves) draws attention squarely to the practitioner and her or his well-being. Genetic counselors are an active ingredient in genetic counseling and therefore must be in top form. She offers strong evidence regarding the importance of caring for one's self in order to maintain one's vitality as a genetic counselor. She also describes a variety of approaches for self-care. Zahm (Chapter 14: Professional Development: Reflective Genetic Counseling Practice) discusses compelling evidence that practice in the absence of self-reflection may lead to stagnation and even deterioration. She suggests several ways that genetic counselors might challenge themselves toward greater self-awareness in order to promote further development of their clinical skills. Callanan (Chapter 15: Mobilizing Genetic Counselor Leadership Skills) describes ways in which the genetic counseling world is a great deal larger than one might realize upon graduation. She encourages genetic counselors to recognize the numerous ways in which they might contribute, and she discusses how these contributions reap personal and professional benefits.

DEFINITION OF GENETIC COUNSELING

No advanced skills book would be complete without the inclusion of a definition of genetic counseling, because it provides a broader conceptual umbrella for the numerous processes and outcomes of clinical practice. The definition that best corresponds to the contents of this book is that of Resta and colleagues (2006), members of a National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) task force charged with developing a new definition of genetic counseling:

Genetic counseling is the process of helping people understand and adapt to the medical, psychological and familial implications of genetic contributions to disease. This process integrates the following:

- Interpretation of family and medical histories to assess the chance of disease occurrence or recurrence.

- Education about inheritance, testing, management, prevention, resources and research.

- Counseling to promote informed choices and adaptation to the risk or condition.

Genetic counseling is a communication process in which trained professionals help individuals and families deal with issues associated with the risk of or occurrence of a genetic disorder. (p. 77)

CAVEATS

Some of the advanced genetic counseling skills presented in this book lack a strong research base, because the research has yet to be done. Therefore, some content is grounded more heavily in personal experience and anecdote than in empirical evidence. We encourage readers to reflect critically on the concepts and strategies presented and to determine how these fit their personal style and practice needs. Furthermore, some of the case examples, although clearly illustrating counseling skills, may seem simplistic and/or artificial. The examples and corresponding strategies are intended to serve as a guide for practice and not as a formula for service provision and professional development. Importantly, all cases and examples presented in the chapters have been anonymized.

Each chapter concludes with several learning activities. They are relevant for advanced genetic counseling students in their coursework, supervisors and their students in clinical rotations, genetic counselors in peer supervision groups, and anyone involved in the practice of genetic counseling. Many activities can be modified for use either in groups or individually. We strongly recommend that readers have specific learning outcomes in mind when selecting an activity, as this will help in determining the appropriateness of an activity for a particular audience. Furthermore, explaining the desired learning outcomes to participants will give them a rationale for doing the activity, thus helping to prevent confusion about and/or resistance to the activity.

IN CLOSING

We hope that you will enjoy reading the chapters in this book as much as we have. We further hope that your professional development and genetic counseling practice will benefit from the guidance provided by these authors. We thank the authors for their generous sharing of their expertise. We know that they care, and therefore, we care about what they know.

REFERENCES

Danish SJ (2009). Introduction to Psychological Interviewing. Course syllabus, Department of Psychology, Virginia Comm...