- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Short History of South-East Asia

About this book

The success of the first four editions shows that this book fills a vacuum for readers who wish to learn about the countries of South-East Asia. Recent years have seen a number of important developments all of which are covered here. With the global climate becoming more uncertain and the threat of terrorism spilling over, this book will aid readers' knowledge of this region by addressing its historical past and political future.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

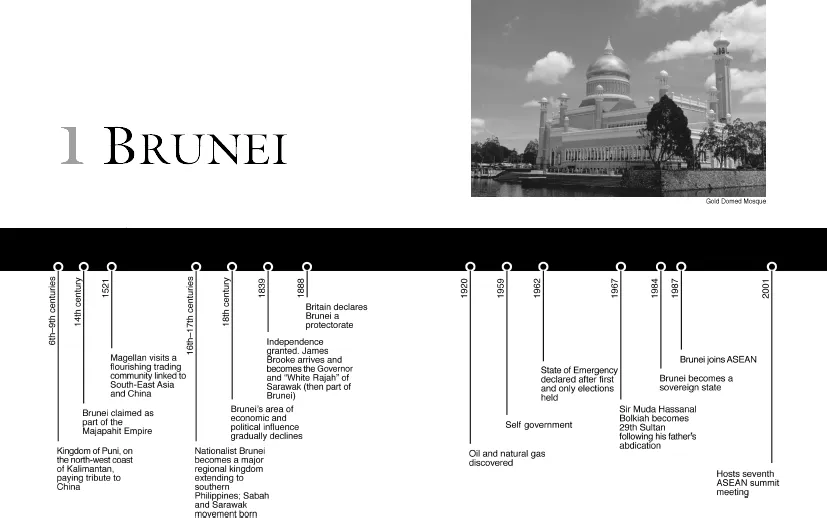

Brunei

Brunei is a small state of just 2,226 square miles located on the north-west coast of the island of Kalimantan, or “Borneo” (a Western term derived from “Brunei”). It is an Islamic State where the sultan, Sir Hassanal Bolkiah, the 29th Sultan in the dynasty, rules by decree. Its population is about 400,000, of whom nearly 60 per cent live in urban areas. Malays comprise about 64 per cent of the population, Chinese about 20 per cent and indigenous tribes about 8 per cent. It would be an unremarkable territory were it not that underneath its soil and under its territorial waters lie huge oil and gas reserves which have enabled the country to boast the highest per-capita income in South-East Asia at around US$27,000. This underground wealth has also enabled one of the world's few remaining absolute monarchies to survive into the 21st century. The sultanate has considerable financial reserves invested overseas.

Early history

Little is known of the early history of Brunei. There appears to have been trade between the north-west coast of Kalimantan and China as early as the sixth century and Brunei was influenced by the spread of Hinduism/Buddhism from India in the first millennium. Chinese records make mention of a kingdom of Puni, located on the north-west coast of Kalimantan, which paid tribute to Chinese emperors between the sixth and the ninth centuries. Brunei was claimed by the great Javanese empire of Majapahit in the 14th century, though it was most likely little more than a trading/tributary relationship. Brunei became a more significant state in the 15th century with a greater degree of independence from its larger neighbours. When the Chinese Admiral Cheng Ho visited Brunei in the early 15th century, as part of his exploration of South-East Asia, he discovered a significant trading port with resident Chinese traders engaged in profitable trade with the homeland.

Brunei was a small cog in the early South-East Asia trading networks but well known enough to figure in the records of the major states. The Brunei ruler seems to have converted to Islam in the middle of the 15th century when he married a daughter of the ruler of Melaka. The Portuguese conquest of Melaka in 1511 closed Melaka to Muslim traders, forcing them to look elsewhere in the archipelago. There was an outflow of wealthy Islamic traders who settled in other parts of the Indonesian archipelago taking with them not only their business acumen but also their religious beliefs. The Islamisation of the archipelago was given a great impetus. Brunei prospered from the Portuguese conquest of Melaka as Islamic traders were now attracted to its port in greater numbers. When Magellan's expedition visited Brunei in 1521 it found a prosperous town with a flourishing trading community linked into the South-East Asia—China trading network. Throughout the 16th century it engaged in political and commercial relations with other states in the Malay world, comprising the Indonesian archipelago, the Malay peninsula and southern Philippines.

Brunei became a major regional kingdom in the 16th and 17th centuries, with its influence stretching into the southern Philippines and its territorial claims extending over most of the north coast of Kalimantan, including what are now the Malaysian states of Sarawak and Sabah. As the first Islamic kingdom in the area, Brunei was the base for the Islamisation of the southern Philippines and surrounding areas, frequently coming into conflict with Catholic Spain after the Spanish conquest of Luzon, the central island of the Philippines. In 1578 Spain attacked Brunei and briefly captured the capital. It was unable to hold the town, in large part because its forces were decimated by sickness. Spain continued to try to conquer the Islamic Sultanate of Sulu in the southern Philippine islands, only finally succeeding in the last quarter of the 19th century.

Brunei did well out of the Portuguese conquest of Melaka. Not only did it become an important port for Muslim traders but it was able to negotiate a deal with the Portuguese for cooperation in the South-East Asian trade with China. Brunei was no threat to Portugal, having no territorial claims outside Kalimantan. It also shared a commercial interest in promoting the China trade. In 1526 the Portuguese established a trading post at Brunei to collect the valued products of Kalimantan and surrounding islands. Brunei became an integral port of call on the Melaka to Macau route.

Brunei's commercial and political power was at its peak in the middle of the 17th century. It had managed to stave off Spain and had reached a mutually beneficial accord with Portugal. From the middle of the 17th century it was increasingly challenged by the Sultanate of Sulu in the islands north-east of Kalimantan. Ostensibly under Brunei suzerainty, the Sultanate of Sulu gradually established total independence, going so far as to acquire from Brunei sovereignty over most of the area which today constitutes the Malaysian state of Sabah.

By the beginning of the 19th century the political and economic power of the Malay rulers in Kalimantan and what is now the southern Philippines was declining sharply. The rule of the once-powerful Sultans of Brunei and Sulu now barely extended outside their capitals. Their decline resulted largely from the development of European entrepots in South-East Asia, which offered local traders a better price for their produce and were free from the taxes of the Malay ports. The development of local trade with European entrepots, especially Singapore, Batavia and Manila, and the decay of the older trading centres of Brunei and Sulu meant a drastic reduction in the Sultanates' revenues, with a consequent decline in political power.

About 40,000 people lived in Brunei town and surrounding areas in the mid 18th century. By the 1830s the population had declined to about 10,000. The northern coast of Kalimantan, except for Brunei town itself, was ruled by local chiefs based at river mouths. The coastal population was predominantly Malay (and Muslim), with a small group of Chinese merchants and pepper growers and a smattering of people of Arab descent. The tribal people who lived in the interior were neither Malay nor Muslim: they were subsistence farmers who traded with the coastal Malays but resisted attempts to bring them under Malay control. To Brunei's south the most significant tribal people were Iban, or Dayak. To the east (in Sabah) the most significant groups were Kadazan-Dusun and Murut.

In addition to its economic decay, the Brunei Sultanate was further weakened by power struggles within the Court. Omar Ali Saifuddin, who succeeded to the throne of the Sultanate in 1828, was a weak ruler. During his reign a bitter power struggle developed between two rival factions led by Brunei Chiefs. The decline in the Sultan's power was evidenced by the increasing independence of provincial rulers, and by the growth in the power of formerly subservient chiefs. In the late 1830s, Sarawak, the westernmost province claimed by the Sultanate of Brunei, was in open rebellion against the local provincial ruler whose rule had become progressively more oppressive as he became more independent of Brunei. In 1837, the Sultan tried to suppress the rebellion but without success.

The British impact

In the first half of the 19th century the interest of the British government and the English East India Company in South-East Asia was limited to the protection of the China trade routes from interference by other European nations and the provision of minimum conditions for the expansion of British trade in the area. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, under which Britain acquired Melaka from the Dutch and relinquished Benkulen on the south-west coast of Sumatra and the Dutch withdrew all objections to Britain's occupation of Singapore, contained articles which guaranteed British traders entry to the Dutch-administered ports and laid down maximum rates of import duties. The failure of the Dutch to carry out the commercial clauses of the Treaty led to a growing agitation by merchants in Singapore and Britain that Britain should directly challenge the Netherlands' position in the archipelago by opening an entrepot to the east of Singapore. The unsuccessful settlements in northern Australia—Melville Bay, Raffles Bay and Port Essington—had been made partly with this end in view, but in the late 1830s attention was focused on the north-west coast of Borneo, the only part of the archipelago not recognised as lying within the Dutch sphere of influence.

Into this situation of a decaying Sultanate of Brunei, facing rebellion in Sarawak, and a growing commercial interest in the north-west coast of Kalimantan by the British community in Singapore, arrived in August 1839 a remarkable Englishman named James Brooke. Brooke was in the mould of the early 19th-century Romantics: he admired what he saw as the simple and unsophisticated life of the peoples of the Malay archipelago and wanted to improve it by bringing to them what he saw as the benefits of British civilisation, without destroying the basic simplicity of their lives. He became convinced that he had a divinely appointed mission in the Malay archipelago. With the proceeds of his wealthy father's estate, he bought a boat and journeyed first to Singapore and then to the north-west coast of Kalimantan. His timely arrival at the head of the Sarawak river with an armed yacht in August 1839 brought the rebellion of the local chief to an end. In return he received the Governorship of Sarawak.

Over the next 30 years Brooke established a personal fiefdom in Sarawak, remorselessly extending its borders at the expense of the Sultanate of Brunei. He was adroit at persuading British naval commanders in Hong Kong and Singapore to support him in forcing the Sultan of Brunei to make concession after concession. However, his attempts to persuade the British government to make Sarawak a British protectorate for the moment fell on deaf ears. The “White Rajah” was one of the more colourful oddities in the history of British colonialism.

A weakened Sultan of Brunei made further concessions of territory in 1877. This time it was to a private company, the American Trading Company, owned by an Austrian and an Englishman. The Austrian sold out to the Englishman in 1881. In order to keep the French and the Germans out of a strategically important area, Britain then granted a royal charter for the establishment of the British North Borneo Company. Further Brunei territory was successfully claimed by Sarawak in 1882, reducing the Sultanate to two small areas: the core around Brunei town and a small pocket of land inside Sarawak. In order to protect what was left of the once great Sultanate of Brunei and finally to ensure that rival European powers were kept out, in 1888 Britain declared a protectorate over Sarawak, Brunei and North Borneo. After a series of arrangements between the British North Borneo Company and Sarawak, which saw Sarawak add further territory, in 1906 Britain appointed a Resident to Brunei in order to supervise the state, modernise its administrative structures and ensure its survival against its predatory Sarawak neighbour.

Brunei had been territorially reduced to a shadow of its former self. But oil and gas were discovered beneath its land and under its territorial waters in the 1920s. The history of Brunei from then on has revolved around the enormous wealth created by oil and gas. The Sultan and his family became very rich very quickly. By the 1960s, access to such a strong revenue stream enabled the Sultanate to provide free health, education and social welfare services of a high standard to all its people, and all with very low rates of taxation.

After World War II and the defeat of Japan, Brunei continued to be a British protectorate with the Sultan ruling with advice from a British resident and under the protection of Gurkha troops. As Britain steadily decolonised in Asia and Africa, this arrangement came to be seen in Britain as anachronistic. In 1959 Brunei achieved self-government, at the insistence of Britain. A constitution was drawn up which provided for elections to a legislative council. In 1962 the first elections were held. They were won by the Partai Rakyat Brunei, a party which opposed the monarchical system and demanded full democratic rights. It also advocated that Brunei join the neighbouring states of Sabah and Sarawak in the mooted Federation of Malaysia. The Partai Rakyat Brunei was strongly opposed by the Sultan and the ruling elite. Its demands were rejected. Brunei was to remain a monarchy.

As a consequence, the Partai Rakyat Brunei launched a revolt. This was quickly crushed by the Gurkha troops stationed in Brunei. The Sultan declared a state of emergency, suspended the constitution, declared the recent elections void and banned the Partai Rakyat Brunei.

This was the only election ever held in Brunei. In 1962 and early 1963 the Sultan became involved in discussions about joining the new Federation of Malaysia. But when Malaysia was formed in September 1963 Brunei elected to remain outside. Disagreements over the distribution of oil and gas revenues (Brunei was determined to protect its revenue) and concern about the relative status of the royal family among the other Malaysian Sultans, all of whom were constitutional monarchs with limited powers, finally decided the Sultan to remain a British protectorate.

The protectorate arrangements were changed in 1971, but Britain still retained control of foreign affairs and defence, although all costs were now met by a very wealthy Sultanate. At the insistence of Britain, embarrassed by the continuation of this relic of colonialism, Brunei became a sovereign state on 1 January 1984.

Independence brought with it few perceptible changes for the people of Brunei. Political parties remain banned. State ministries essentially remain in the hands of members of the royal family and trusted members of a tightly knit elite.

Since the 1960s, Brunei has become increasingly involved with its South-East Asian neighbours. Its relations with ASEAN states since the formation of ASEAN in 1967 have been extremely good, although from time to time there has been some debate in sections of Malaysian society about the merits of Brunei's benevolent but authoritarian monarchy, and in 2003 and 2004 the two countries became involved in a dispute over rival claims to oil fields off the coast of Borneo.

In 1987 Brunei joined ASEAN as a full member, thereby formalising the already close relationship, and in November 2001 staged the seventh ASEAN summit meeting, with representatives of China, Japan and Korea in attendance. In July 2002, the country hosted the ASEAN Regional Forum in which ASEAN's members and the United States signed a pact pledging to “prevent, disrupt and combat” global terrorism. In December the same year, the Sultan met President George W. Bush in Washington and affirmed the two countries' close ties, although Brunei has discreetly sought to distance itself from the US invasion of Iraq.

In 1998 the business empire run by the Sultan's brother, Prince Jefri, collapsed amid allegations of fraud and mismanagement. The failure of his conglomerate is believed to have resulted in debts to the Sultanate of US$15 billion. Prince Jefri had formerly been finance minister between 1986–1997 and was dismissed as head of the Brunei Investment Agency—which manages the country's overseas investments—in 1998.

Brunei in the New Millennium

Brunei's revenues are almost entirely dependent on royalties from oil and gas. Conscious of the eventual exhaustion of oil and gas (predicted to occur around 2025), since the mid 1980s Brunei's government has placed priority on developing the agricultural sector so that it can cease to be a net importer of food. Efforts have also been made to develop light manufacturing. But realistically, the country's inherent structural and capacity constraints mitigate against the development of a diversified industrial base. These include high labour costs, a shortage of skilled labour, a small domestic market, the lack of an entrepreneurial class and a large (relative to the population) bureaucracy.

In 2003, plans were announced to corporatise the Department of Telecommunications as part of an ongoing programme to corporatise government authorities to encourage them to become more accountable and competitive. Following lengthy delays, this department was finally corporatised in 2006, with its duties shared between a telecommunications carrier set up in 2002 (TelBru) and the Authority for Info-Communications Technology Industry, which took on a regulatory and facilitation function.

Policies aimed at economic diversification and weaning the population off government dependency have been only partially successful and, approximately 70 per cent of the workforce remains on the state payroll. The government has also invested tens of billions of petro-dollars in the West in order that the accrued income will act to cushion the economic—and no doubt, social—effects brought on by declining fossil-fuel revenues. Such diversified long-term investments offshore will also help smooth out unpredictable short-term fluctuations in the global price of oil, which in 2008–9 alone swung between US$147 and US$40 per barrel due to flow-on effects on oil demand caused by the onset of the global credit crisis and the subsequent world economic downtown.

The social composition of Brunei has changed quickly over the past five decades, most noticeable in the growth of an educated middle c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Brunei

- Chapter 2: Cambodia

- Chapter 3: East Timor

- Chapter 4: Indonesia

- Chapter 5: Lao PDR

- Chapter 6: Malaysia

- Chapter 7: Myanmar

- Chapter 8: Philippines

- Chapter 9: Singapore

- Chapter 10: Thailand

- Chapter 11: Vietnam

- Further Reading

- Maps

- About AFG Venture Group

- About Blake Dawson

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Short History of South-East Asia by Peter Church in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.