- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This comprehensive, unified text on the principles and practice of clinical trials presents a detailed account of how to conduct the trials. It describes the design, analysis, and interpretation of clinical trials in a non-technical manner and provides a general perspective on their historical development, current status, and future strategy. Features examples derived from the author's personal experience.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction: The Rationale of Clinical Trials

The evaluation of possible improvements in the treatment of disease has historically been an inefficient and haphazard process. Only in recent years has it become widely recognized that properly conducted clinical trials, which follow the principles of scientific experimentation, provide the only reliable basis for evaluating the efficacy and safety of new treatments. The major objective of this book is therefore to explain the main scientific and statistical issues which are vital to the conduct of effective and meaningful clinical research. In addition, some of the ethical and organizational problems of clinical trials will be discussed. The historical perspective, current status and future strategy for clinical trials provide a contextual framework for these methodological aspects.

In section 1.1, I discuss what constitutes a clinical trial and how clinical trials may usefully be classified. Section 1.2 deals with the underlying rationale for randomized controlled clinical trials and their relation to the scientific method. Section 1.3 goes on to describe one particular example, a clinical trial for primary breast cancer, as an illustration of how adherence to sound scientific principles led to an important advance in treatment.

1.1 TYPES OF CLINICAL TRIAL

Firstly, we need to define exactly what is meant by a‘clinical trial’: briefly the term may be applied to any form of planned experiment which involves patients and is designed to elucidate the most appropriate treatment of future patients with a given medical condition. Perhaps the essential characteristic of a clinical trial is that one uses results based on a limited sample of patients to make inferences about how treatment should be conducted in the general population of patients who will require treatment in the future.

Animal studies clearly do not come within this definition and experiments on healthy human volunteers are somewhat borderline in that they provide only indirect evidence of effects on patients. However, such volunteer studies (often termed phase I trials) are an important first step in human exposure to potential new treatments and hence are included in our definition when appropriate.

Field trials of vaccines and primary prevention trials for subjects with presymptomatic conditions (e.g. high serum cholesterol) involve many of the same scientific and ethical issues as in the treatment of patients who are clearly diseased, and hence will also be mentioned when appropriate.

An individual case study, whereby one patient’s pattern of treatment and response is reported as an interesting occurrence, does not really constitute a clinical trial. Since biological variation is such that patients with the same condition will almost certainly show varied responses to a given treatment, experience in one individual does not adequately enable inferences to be made about the general prospects for treating future patients in the same way. Thus, clinical trials inevitably require groups of patients: indeed one of the main problems is to get large enough groups of patients on different treatments to make reliable treatment comparisons.

Another issue concerns retrospective surveys which examine the outcomes of past patients treated in a variety of ways. These unplanned observational studies contain serious potential biases (e.g. more intensive treatments given to poorer prognosis patients may appear artificially inferior) so that they can rarely make a convincing contribution to the evaluation of alternative therapies. Hence, except in chapter 4 when considering the inadequacies of non-randomized trials, such studies will not be considered as clinical trials.

It is useful at this early stage to consider various ways of classifying clinical trials. Firstly, there is the type of treatment: the great majority of clinical trials are concerned with the evaluation of drug therapy more often than not with pharmaceutical company interest and financial backing. However, clinical trials may also be concerned with other forms of treatment. For instance, surgical procedures, radiotherapy for cancer, different forms of medical advice (e.g. diet and exercise policy after a heart attack) and alternative approaches to patient management (e.g. home or hospital care after inguinal hernia operation) should all be considered as forms of treatment which may be evaluated by clinical trials. Unfortunately, there has generally been inadequate use of well-designed clinical trials to evaluate these other non-pharmaceutical aspects of patient treatment and care, a theme which I shall return to later.

Drug trials within the pharmaceutical industry are often classified into four main phases of experimentation. These four phases are a general guideline as to how the clinical trials research programme for a new treatment in a specific disease might develop, and should not be taken as a hard and fast rule.

Phase I Trials: Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicity

These first experiments in man are primarily concerned with drug safety, not efficacy, and hence are usually performed on human volunteers, often pharmaceutical company employees. The first objective is to determine an acceptable single drug dosage (i.e. how much drug can be given without causing serious side-effects). Such information is often obtained from dose-escalation experiments, whereby a volunteer is subjected to increasing doses of the drug according to a predetermined schedule. Phase I will also involve studies of drug metabolism and bioavailability and, later, studies of multiple doses will be undertaken to determine appropriate dose schedules for use in phase II. After studies in normal volunteers, the initial trials in patients will also be of the phase I type. Typically, phase I studies might require a total of around 20-80 subjects and patients.

Phase II Trials: Initial Clinical Investigation for Treatment Effect

These are fairly small-scale investigations into the effectiveness and safety of a drug, and require close monitoring of each patient. Phase II trials can sometimes be set up as a screening process to select out those relatively few drugs of genuine potential from the larger number of drugs which are inactive or over-toxic, so that the chosen drugs may proceed to phase III trials. Seldom will phase II go beyond 100-200 patients on a drug.

Phase III Trials: Full-scale Evaluation of Treatment

After a drug is shown to be reasonably effective, it is essential to compare it with the current standard treatment(s) for the same condition in a large trial involving a substantial number of patients. To some people the term ‘clinical trial’ is synonymous with such a full-scale phase III trial, which is the most rigorous and extensive type of scientific clinical investigation of a new treatment. Accordingly , much of this book is devoted to the principles of phase III trials.

Phase IV Trials: Postmarketing Surveillance

After the research programme leading to a drug being approved for marketing, there remain substantial enquiries still to be undertaken as regards monitoring for adverse effects and additional large-scale, long-term studies of morbidity and mortality. Also the term ‘phase IV trials’ is sometimes used to describe promotion exercises aimed at bringing a new drug to the attention of a large number of clinicians, typically in general practice. This latter type of enquiry has limited scientific value and hence should not be considered part of clinical trial research.

This categorization of pharmaceutical company sponsored drug trials is inevitably an oversimplification of the real progress of a drug’s clinical research programme. However, it serves to emphasize that there are important early human studies (phases I/II), with their own particular organizational, ethical and scientific problems, which need to be completed before full-scale phase III trials are undertaken. The Food and Drug Administration (1977) have issued guidelines for drug development programmes in the United States. The guidelines include recommendations on how phase I-III trials should be structured for drugs in 15 specific disease areas.

It should be remembered that each pharmaceutical company has an equally important preclinical research programme, which includes the synthesis of new drugs and animal studies for evaluating drug metabolism and later for testing efficacy and especially potential toxicity of a drug. The scale and scientific quality of these animal experiments have increased enormously, following legislation in many countries prompted by the thalidomide disaster. In particular any drug must pass rigorous safety tests in animals before it can be approved for clinical trials.

The phase I-III classification system may also be of general guidance for clinical trials not related to the pharmaceutical industry. For instance, cancer chemotherapy and radiotherapy research programmes, which take up a sizeable portion of the U.S. National Institutes of Health funding, can be conveniently organized in terms of phases I-III. In this context, phase I trials are necessarily on patients, rather than normal volunteers, due to the highly toxic nature of the treatments.

Development of new surgical procedures will also follow broadly similar plans, with phase I considered as basic development of surgical techniques. However, there is a paucity of well-designed phase III trials in surgery.

1.2 CONTROLLED CLINICAL TRIALS AND THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD

I will now concentrate on full-scale (phase III) trials and consider the scientific rationale for their conduct. Of course, the first priority for clinical research is to come up with a good idea for improving treatment. Progress can only be achieved if clinical researchers with insight and imagination can propose therapeutic innovations which appear to have a realistic chance of patient benefit. Naturally, the proponents of any new therapy are liable to be enthusiastic about its potential: preclinical studies and early phase I/II trials may indicate considerable promise. In particular, a pharmaceutical company can be very persuasive about its product before any full-scale trial is undertaken. Unfortunately, many new treatments turn out not to be as effective as was expected: once they are subjected to the rigorous test of a properly designed phase III trial many therapies fail to live up to expectation; see Gilbert et al. (1977) for examples in surgery and anaesthesia.

One fundamental rule is that phase III trials are comparative. That is, one needs to compare the experience of a group of patients on the new treatment with a control group of similar patients receiving a standard treatment. If there is no standard treatment of any real value, then it is often appropriate to have a control group of untreated patients. Also, in order to obtain an unbiassed evaluation of the new treatment’s value one usually needs to assign each patient randomly to either new or standard treatment (see chapters 4 and 5 for details). Hence it is now generally accepted that the randomized controlled trial is the most reliable method of conducting clinical research.

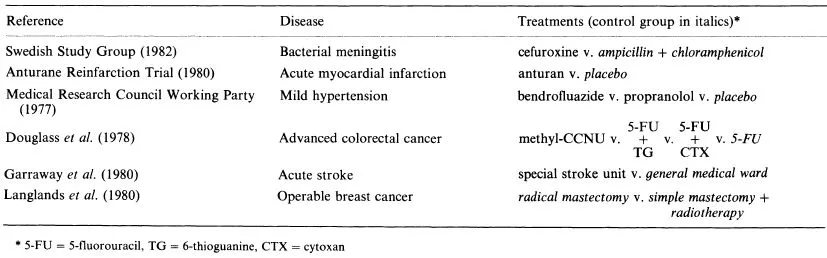

At this point it is of value to present a few examples of randomized controlled trials to illustrate the use of control groups. Table 1.1 lists the six trials I wish to consider.

The first trial, for bacterial meningitis, represents the straightforward situation where a new treatment (cefuroxine) was compared with a standard treatment (the combination of ampicillin and chloramphenicol) to see if the former was more effective in killing the bacterium.

The anturan trial reflects another common situation where the new treatment (anturan) is to be compared with a placebo (inactive oral tablets that the patients could not distinguish from anturan). Thus, the control group of myocardial infarction patients did not receive any active treatment. The aim was to see if anturan could reduce mortality in the first year after an infarct.

The mild hypertension trial has two active treatments which are to be compared with placebo to see if either can reduce morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular-renal causes.

The trial for advanced colorectal cancer is unusual in having three new treatments to compare with the standard drug 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). Two of the new treatments consisted of 5-FU in combination with other drugs. Most trials have just two treatment groups (new vs. standard) and in general one needs to be wary of including more treatments since it becomes more difficult to get sufficient patients per treatment.

The last two trials in Table 1.1 are included as reminders that clinical trials can be used to evaluate aspects of treatment other than drug therapy. The stroke trial is concerned with patient management: can one improve recovery by caring for patients in a special stroke unit rather than in general medical wards?

The breast cancer trial represents an unusual situation in that it set out to compare two treatments (radical mastectomy or simple mastectomy + radiotherapy) each of which is standard practice depending on the hospital. In a sense each treatment is a control for the other. Such trials can be extremely important in resolving long-standing therapeutic controversies which have previously never been tested by a randomized controlled trial.

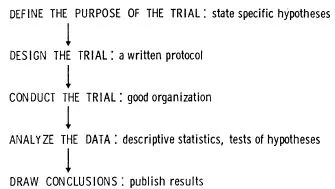

I now wish to consider how a clinical trial should proceed if the principles of the scientific method are to be followed. Figure 1.1 shows the general sequence of events. From an initial idea about a possible improvement in therapy one needs to produce a more precise definition of trial aims in terms of specific hypotheses regarding treatment efficacy and safety. That is, one must define exactly the type of patient, the treatments to be compared and the methods of evaluating each patient’s response to treatment.

The next step is to develop a detailed design for a randomized trial and document one’s plan in a study protocol. The design needs to fulfil scientific, ethical and organizational requirements so that the trial itself may be conducted efficiently and according to plan. Two principal issues here are:

Table 1.1. Some examples of randomized controlled trials

(a) Size The trial must recruit enough patients to obtain a reasonably precise estimate of response on each treatment.

(b) Avoidance of bias The selection, ancillary care and evaluation of patients should not differ between treatments, so that the treatment comparison is not affected by factors unrelated to the treatments themselves.

Statistical methods should be applied to the results in order to test the prespecified study hypotheses. In particular, one may use significance tests to assess how strong the evidence is for a genuine difference in response to treatment. Finally, one needs to draw conclusions regarding the treatments’ relative merits and publish the results so that other clinicians may apply the findings.

Fig. 1.1. The scientific method as applied to clinical trials

The aim of any clinical trial should be to obtain a truthful answer to a relevant medical issue. This requires that the conclusions be based on an unbiassed assessment of objective evidence rather than on a subjective compilation of clinical opinion. Historically, progress in clinical research has been greatly hindered by an inadequate appreciation of the essential methodology for clinical trials. After a brief historical review in chapter 2, the remainder of this book is concerned with a more extensive and practical account of this methodology. As a useful introduction to the main concepts, I now wish to focus on one particular trial for primary breast cancer.

1.3 AN EXAMPLE OF A CLINICAL TRIAL FOR PRIMARY BREAST CANCER

In 1972 a clinical trial was undertaken in the United States to evaluate whether the drug L-Pam (1-phenylalanine mustard) was of value in the treatment of primary breast cancer following a radical mastectomy. Fisher et al. (1975) presented the early findings with a subsequent update by Fisher et al. (1977). We now consider the development of this trial in the context of the scientific method outlined in figure 1.1.

(1) Purpose of the Trial

Earlier clinical trials for the treatment of patients with advanced (metastatic) breast cancer had shown that L-Pam was one of a number of drugs which could cause temporary shrinkage of tumours and increase survival in some patients. Therefore, it seemed sensible to argue that for patients with primary breast cancer who might still have an undetected small trace of tumour cells present after mastectomy, a drug such as L-Pam could be effective in killing off such cells and hence preventing subsequent disease recurrence. Such a general concept is an essential preliminary for a worthwhile clinical trial, but more precise specific hypotheses must be defined before a trial can be planned properly. There are four basic issues in this regard: the precise definition of (1) the patients eligible for study, (2) the treatment, (3) the end-points for evaluating each patient’s response to treatment, and (4) the need for comparison with a control group of patients not receiving the new treatment. In this case these four issues were resolved as follows:

Eligible patients were defined as having had a radical mastectomy for primary breast cancer with histologically confirmed axillary node involvement. Patients were excluded if they had certain complications such as peau d’orange, skin ulceration, etc., or if they were aged over 75, were pregnant or lactating. Thus the trial focussed on those patients who were considered most likely to benefit from L-Pam if indeed it conferred any benefit at all.

Treatment was defined as L-Pam to be given orally at a dose of 0.15 mg/kg body weight for five consecutive days every six weeks, this dose schedule having been well established from studies in advanced breast cancer. Since haematologic toxicity will occur in some patients, dose modifications were defined as follows: reduce dose by half if p...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- 1: Introduction: The Rationale of Clinical Trials

- 2: The Historical Development of Clinical Trials

- 3: Organization and Planning

- 4: The Justification for Randomized Controlled Trials

- 5: Methods of Randomization

- 6: Blinding and Placebos

- 7: Ethical Issues

- 8: Crossover Trials

- 9: The Size of a Clinical Trial

- 10: Monitoring Trial Progress

- 11: Forms and Data Management

- 12: Protocol Deviation

- 13: Basic Principles of Statistical Analysis

- 14: Further Aspects of Data Analysis

- 15: Publication and Interpretation of Findings

- Reference

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Clinical Trials by Stuart J. Pocock in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Médecine & Pharmacologie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.