![]()

PART ONE

WHAT IS 21ST CENTURY LEARNING?

![]()

1

Learning Past and Future

We are currently preparing students for jobs that don’t yet exist . . . using technologies that haven’t yet been invented . . . in order to solve problems we don’t even know are problems yet.

—Richard Riley, Secretary of Education under Clinton

It happened quietly, without fanfare or fireworks. In 1991, the total money spent on Industrial Age goods in the United States—things like engines and machines for agriculture, mining, construction, manufacturing, transportation, energy production, and so on—was exceeded for the first time in history by the amount spent on information and communications technologies: computers, servers, printers, software, phones, networking devices and systems, and the like.

The score? In 1991, “Knowledge Age” expenditures exceeded Industrial Age spending by $5 billion ($112 billion versus $107 billion). That year marked year one of a new age of information, knowledge, and innovation.1 Since then, countries around the globe have increasingly been spending more on making, manipulating, managing, and moving bits and bytes of information than on handling the material world’s atoms and molecules.

This monumental shift from Industrial Age production to that of the Knowledge Age economy—information-driven, globally networked—is as world-changing and life-altering as the shift from the Agrarian to the Industrial Age three hundred and fifty years ago.

Moving from a primarily nuts-and-bolts factory and manufacturing economy to one based on data, information, knowledge, and expertise has had a huge impact on the world’s economies and our everyday lives. The sequence of steps to produce a product or service, the so-called value chain of work, has dramatically shifted, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Industrial economies are focused on turning natural resources such as iron and crude oil into products we use—automobiles and gasoline. Knowledge economies turn information, expertise, and technological innovations into services we need, like medical care and cell phone coverage.

This of course doesn’t mean that Industrial Age work will or can go away in the Knowledge Age—manufactured products will always be needed.

It does mean that with increasing automation and the shifting of manufacturing (and its environmental impacts) to lower-wage, industrial-equipped countries such as China, India, and Brazil, industrial work in Knowledge Age countries will continue to decline and service-based knowledge work will continue to grow well into the 21st century.

Industrial Age Value Chain

Extraction →Manufacturing →Assembly →Marketing →Distribution →

Products (and Services)

Knowledge Age Value Chain

Data → Information → Knowledge → Expertise → Marketing →

Services (and Products)

Figure 1.1. Value Chains Then and Now.

But that’s only one of a whole bundle of big changes that have arrived at our doorstep in the early part of the 21st century. And these changes will continue to make new demands on education as the century progresses.

As Thomas Friedman vividly reported in

The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century and in

Hot, Flat, and Crowded, the 21st century is challenging and reshuffling the very foundations of our society in new, powerful, and often alarming ways. For example:

• The world now has a truly global financial and economic ecosystem. This highly interlinked system means that a disruption in one part of the world (such as a U.S. housing loan crisis) has dire consequences to economies everywhere.

• The growing disparity in the world between rich and poor leads to social tension, conflicts, extremism, and a less safe world for everyone.

Yet the biggest challenge to the survival of all societies is the strain we’re placing on our physical environment:

• Global population has risen from 2.5 billion in 1950 to nearly 7 billion in 2009. This figure is expected to exceed 9 billion by 2050.

• Despite widespread poverty, increasing numbers of people are rising into middle-class lifestyles, which drastically increases their consumption of the earth’s material and energy resources.

• Increased consumption of resources is causing climate change and other threats to the natural world and its global life-support systems.

Add up overpopulation, overconsumption, increased global competition and interdependence, melting ice caps, financial meltdowns, and wars and other threats to security, and you get quite a bumpy beginning for our new century!

But as the Chinese characters for the word crisis (shown in Figure 1.2) suggest, in times such as these, along with danger and despair come great opportunities for change and renewed hope.

One of education’s chief roles is to prepare future workers and citizens to deal with the challenges of their times. Knowledge work—the kind of work that most people will need in the coming decades—can be done anywhere by anyone who has the expertise, a cell phone, a laptop, and an Internet connection. But to have expert knowledge workers, every country needs an education system that produces them; therefore, education becomes the key to economic survival in the 21st century.

To further understand what our times demand of education we must take a closer look at the changing world of 21st century work.

Figure 1.2. Signs for Our Times.

Learning a Living: The Future of Work and Careers

A few years ago, four hundred hiring executives of major corporations were asked a very simple but significant question: “Are students graduating from school really ready to work?” The executives’ collective answer? Not really.2

The study clearly showed that students graduating from secondary schools, technical colleges, and universities are sorely lacking in some basic skills and a large number of applied skills:

• Oral and written communications

• Critical thinking and problem solving

• Professionalism and work ethic

• Teamwork and collaboration

• Working in diverse teams

• Applying technology

• Leadership and project management

Reports from around the world confirm that this “21st century skills gap” is costing business a great deal of money. Some estimate that well over $200 billion a year is spent worldwide in finding and hiring scarce, highly skilled talent, and in bringing new employees up to required skill levels through costly training programs. And as budgets tighten further in tough economic times, companies need highly competent employees ready to hit the ground running without extra training and development costs.

The competitiveness and wealth of corporations and countries is completely dependent on having a well-educated workforce—as one 2006 report called it, “Learning Is Earning.” Improving a country’s literacy rate by a small amount can have huge positive economic impacts. Education also increases the earning potential of workers—an additional year of schooling can improve a person’s lifetime wages by 10 percent or more.3

So why is education falling short in preparing students for 21st century work?

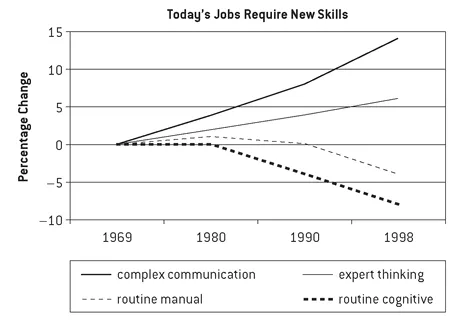

The world of Knowledge Age work requires a new mix of skills. Jobs that require routine manual and thinking skills are giving way to jobs that involve higher levels of knowledge and applied skills like expert thinking and complex communicating (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3. New Skills for 21st Century Work.

Source: Adapted from Levy and Murnane, 2004.

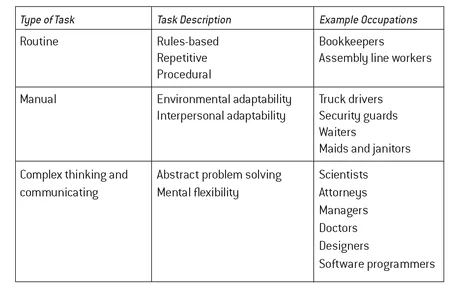

Table 1.1 lists examples of jobs requiring routine and manual skills and those with high demands for complex communicating and thinking skills.

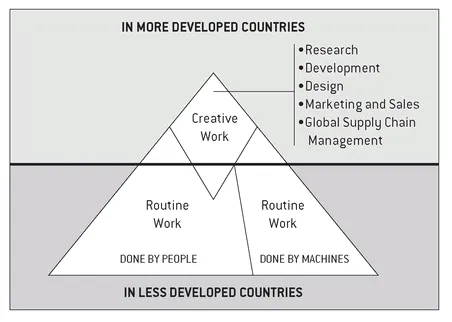

The rising demand for a highly skilled workforce also means that there will be a growing income gap between less educated, relatively unskilled workers and highly educated, highly skilled workers. Routine tasks are increasingly being automated, and the routine jobs still done by people barely paid a living wage. Routine work is moving to countries where the cost of labor is very low, as shown in Figure 1.4.

Our world’s education systems must now prepare as many students as possible for jobs at the top of the chart—the high-paying knowledge work jobs of today and tomorrow that require complex skills, expertise, and creativity. And many of the jobs of the future do not even exist today!

Table 1.1. Jobs and 21st Century Work.

Source: Adapted from Autor, 2007.

Figure 1.4. The Future of 21st Century Work.

Source: Adapted from National Center on Education and the Economy, 2007.

If all these changes weren’t quite enough, students in school today can expect to have more than eleven different jobs between the ages of eighteen and forty-two.4 We don’t know yet how many more job changes to expect after age forty-two, but with increasing life expectancy, the number could easily double to twenty-two or more total jobs in a lifetime!

What is certain is that two essential skill sets will remain at the top of the list of job requirements for 21st century work:

• The ability to quickly acquire and apply new knowledge

• The know-how to apply essential 21st century skills—problem solving, communication, teamwork, technology use, innovation, and the rest—to each and every project, the primary unit of 21st century work

To get a better sense of the rising importance learning and education are playing in our lives today, it’s useful to step back and take a look at the roles education has played in the past, where learning is heading, and the forces driving these changes.

Learning Through Time

Currently, nearly 1.5 billion children attend primary and secondary schools in the world—around 77 percent of all school-age children.5

A billion and a half schoolchildren is a staggering number, even though it leaves out another three hundred million and more worldwide—most of them girls—who have no access to basic education. Still, just imagine, as the sun rises across each time zone, all those mothers and fathers waking up their children, making sure they are washed and appropriately dressed, have (hopefully) eaten some breakfast, and have gotten off to school on time—each and every day of the school year!

But why is education so important that virtually every country in the world has implemented some sort of formal education system? Why has the United Nations declared it a fundamental right of all children?6

And what do parents, teachers, businesses, soci...