![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Electrodynamics of Left-Handed Media

1.1 INTRODUCTION

Continuous media with negative parameters, that is, media with negative dielectric constant, ε, or magnetic permeability, μ, have long been known in electromagnetic theory. In fact, the Drude–Lorentz model (which is applicable to most materials) predicts regions of negative ε or μ just above each resonance, provided losses are small enough [1]. Although losses usually prevent the onset of this property in common dielectrics, media with negative ε can be found in nature. The best-known examples are low-loss plasmas, and metals and semiconductors at optical and infrared frequencies (sometimes called solid-state plasmas). Media with negative μ are less common in nature due to the weak magnetic interactions in most solid-state materials [2]. Only in ferrimagnetic materials are magnetic interactions strong enough (and losses small enough) to produce regions of negative magnetic permeability. Ferrites magnetized to saturation present a tensor magnetic permeability with negative elements near the ferrimagnetic resonance (which usually occurs at microwave frequencies). These materials are widely used in microwave engineering, mainly to make use of their non-reciprocity. The electrodynamics of these solid-state materials with negative ε or μ is described in many well-known textbooks [3–5], so this chapter will focus on the electrodynamics of media having simultaneously negative ε and μ (see, however, problems 1.1–1.3, 1.12, and 1.14).

Wave propagation in media with simultaneously negative ε and μ was discussed and analyzed in a seminal paper by Veselago [6] at the end of the 1960s. However, it was necessary to wait for more than 30 years to see the first practical realization of such media [7], also called left-handed media [6,7]. This terminology will be used throughout this book.1 Other terms that have been proposed for media with simultaneously negative ε and μ are negative-refractive media [8], backward media [9], double-negative media [10], and also Veselago media [11].

The propagation constant of a plane wave is given by

, so it is apparent that wave propagation is not forbidden in left-handed media. Several principal questions arise from this statement:

- Does an electromagnetic wave in a left-handed medium differ in any essential way from a wave in an ordinary medium with positive ε and μ?

- Is there any essential physical law—for instance, energy conservation—forbidding left-handed media?

- Assuming the answer to the previous question was affirmative. How to obtain a left-handed medium in practice?

In this chapter we will try to give some answers to the first and second questions above, leaving the following chapters to find the answer to the third question.

1.2 WAVE PROPAGATIO IN LEFT-HANDED MEDIA

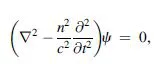

In order to show wave propagation in left-handed media, we will first reduce Maxwell equations to the wave equation [6]:

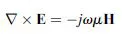

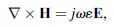

where n is the refractive index, c is the velocity of light in vacuum, and n2/c2 = εμ. As the squared refractive index n2 is not affected by a simultaneous change of sign in ε and μ, it is clear that low-loss left-handed media must be transparent. In view of the above equation, we can obtain the impression that solutions to equation (1.1) will remain unchanged after a simultaneous change of the signs of ε and μ. However, when Maxwell’s first-order differential equations are explicitly considered,

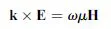

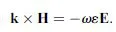

it becomes apparent that these solutions are quite different. In fact, for plane-wave fields of the kind E = E0 exp(–jk.r + jωt) and H = H0 exp(–jk. r + jωt) (this space and time field dependence will be implicitly assumed throughout this book), the above equations reduce to

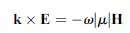

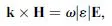

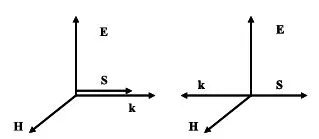

Therefore, for positive ε and μ, E, H, and k form a right-handed orthogonal system of vectors. However, if ε < 0 and μ < 0, then equations (1.4) and (1.5) can be rewritten as

showing that E, H, and k now form a left-handed triplet, as illustrated in Figure 1.1. In fact, this result is the original reason for the denomination of negative ε and μ media as “left-handed” media [6].

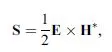

The main physical implication of the aforementioned analysis is backward-wave propagation (for this reason, the term backward media has been also proposed for media with negative ε and μ [9]). In fact, the direction of the time-averaged flux of energy is determined by the real part of the Poynting vector,

which is unaffected by a simultaneous change of sign of ε and μ. Thus, E, H, and S still form a right-handed triplet in a left-handed medium. Therefore, in such media, energy and wavefronts travel in opposite directions (backward propagation). Backward-wave propagation is a well-known phenomenon that may appear in non-uniform waveguides [12,13]. However, backward-wave propagation in unbounded homogeneous isotropic media seems to be a unique property of left-handed media. As will be shown, most of the surprising unique electromagnetic properties of these media arise from this backward propagation property.

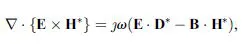

So far, we have neglected losses. However, losses are unavoidable in any practical material. In the following, the effect of losses in plane-wave propagation will be considered. To begin, we will consider a finite region filled by a homogeneous left-handed medium. In the steady state, and provided there are no sources inside the region, there must be some power flow into the region in order to compensate for losses. Thus, from the well-known complex Poynting theorem [14],

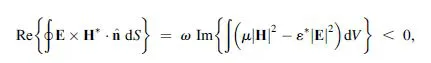

it follows that

where integration is carried out over the aforementioned region. Therefore,

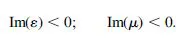

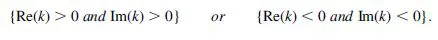

Let us now consider a plane wave with square wave number k2 = ω2με, propagating in a lossy left-handed medium with Re(ε) < 0 and Re(μ) < 0. From expression (1.11), it follows that Im(k2) > 0. Therefore

That is, waves grow in the direction of propagation of the wavefronts. This fact is in agreement with the aforementioned backward-wave propagation.

1.3 ENERGY DENSITY AND GROUP VELOCITY

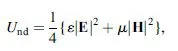

If negative values for ε and μ are introduced in the usual expression for the time-averaged density of energy in transparent nondispersive media, Und, given by

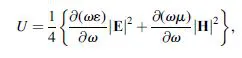

they produce the nonphysical result of a negative density of energy. However, as is well known, any physical media other than vacuum must be dispersive [1], equation (1.13) being an approximation only valid for very weakly dispersive media. The correct expression for a quasimonochromatic wavepacket traveling in a dispersive media is [2]

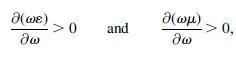

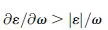

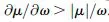

where the derivatives are evaluated at the central frequency of the wavepacket. Thus, the physical requirement of positive energy density implies that

which are compatible with

ε < 0 and

μ < 0 provided

and

. Therefore, physical left-handed media must be highly dispersive. This fact is in agreement with the low-loss Drude-Lorentz model for

ε and

μ, which predicts negative values for

ε and/or

μ in the highly dispersive regions just above the resonances [1]. Finally, it must be mentioned that the usual interpretation of the imaginary part of the complex Poynting theorem, which relates the flux of reactive power through a closed surface with the difference ...