eBook - ePub

globalization

n. the irrational fear that someone in China will take your job

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

globalization

n. the irrational fear that someone in China will take your job

About this book

In Globalization, authors Bruce Greenwald and Judd Kahn cut through the myths surrounding globalization and look more closely at its real impact, presenting a more accurate picture of the present status of globalization and its future consequences. Page by page, they uncover the real facts about globalization and answer the most important questions it raises, including: Will globalization increase or diminish in economic importance? Do higher living standards depend more on global or local conditions–and What are the actual implications of globalization for financial markets?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access globalization by Bruce C. N. Greenwald,Judd Kahn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Globalisation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

GlobalisationChapter 1

It May Be News, But It Isn’t New

A Brief History of Globalization

Globalization has a history, though it is hard to say precisely when it began. The Roman Empire doesn’t qualify as global, because despite its enormous expanse and a certain level of economic activity between the parts, most of the world was still outside its boundaries and most production remained local. The British Empire in 1815, after Waterloo, had an even larger footprint, but international trade was insignificant and one of the original purposes of the empire was to give Britain privileged access to its colonies, as both sources of raw material and markets for its goods. However, later in the nineteenth century, Britain led the move to reduce barriers to trade. At the same time, the telegraph, steam transportation, and other technologies shrank the time and the cost of moving information and goods, and people began to migrate in large numbers. Economic and social activity across national boundaries grew in importance and began to attract notice.

In his classic book, The Great Illusion, British writer Norman Angell argue that, due to what we now call globalization , the nation-state had declined as a factor in economic performance. The two great economic forces, capital and labor, had become fully internationalized, cutting across state borders. According to Angell, international finance had “become so independent and interwoven with trade and industry . . . that political and military power can in reality do nothing for trade . . . and all these factors are making rapidly for the disappearance of state rivalries.”1 As a consequence, wars could no longer be fought profitably and were therefore becoming outmoded. Nearly a century later, Thomas Friedman reaffirm this analysis: “As countries [get] woven into the fabric of global trade and rising living . . . standard, the cost of war for the victor and vanquished [becomes] prohibitively high.”2

Angell received a Nobel Prize in 1933, but he won it for peace, not for prophecy. The Great Illusion originally appeared in 1909 and was soon overtaken by events.3 He was tragically wrong about modern industrial states not going to war against one another, as World War I demonstrated with the blood of millions. But he was also mistaken about a future of ever-increasing economic internationalization and the diminishing importance of national boundaries. The rapid advance of transportation and communication technologies did not lead to a more interdependent economic world, at least not right away. Globalization, whether measured by trade, movements of capital, or emigration, peaked between 1910 and 1920, and then declined steadily for the next 30 to 40 years. Thomas Friedman may prove a better forecaster than Norman Angell, but we think that is unlikely.

Tradable Goods

Trade occurs when people in one country want something provided elsewhere, because it is better, cheaper, or locally unavailable. The growth of trade within any particular category of goods depends on falling transportation, communications, and financing costs. It also depends on the absence of prohibitive government interference, through measures such as tariffs or quotas imposed on imported goods.

Some kinds of output are inherently easier to trade across national boundaries than others; grain travels better than child care, for example. The overall importance of global trade depends on the mix of final demand between easily traded goods and goods that don’t travel well. Shifts in demand toward nontraded goods (and services) may outweigh the effects of improvements in transportation, communications, and financing, and government reductions in legislated barriers to trade. In that case, globalization declines as a factor in overall economic life, despite trade-enhancing improvements. A decline of this sort occurred in the 1920s, as trade as a portion of economic output shrank. We think a similar decline is almost certain to happen in the foreseeable future.

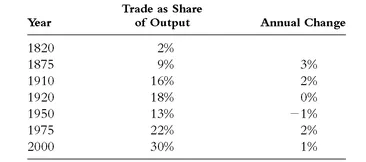

The volume and importance of international trade has moved up and down over the last 200 years. Starting early in the nineteenth century, continual improvements in transportation and communications led to a steady growth in the importance of international trade relative to overall economic activity. From 2 percent of total output in 1820, trade grew to 9 percent by 1875 (a 4.5-fold increase) and then to 18 percent in 1920 (a twofold increase).4 Table 1.1 presents an abridged view of this history.

Table 1.1 Global Trade as Share of Global Output

SOURCE: A. Estevadeordal, B. Frantz, A.M. Taylor, “The Rise and Fall of World Trade, 1970-1979,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, May 2003, and International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics.

Even during this boom period, the law of diminishing returns set in. In the first 55 years, from 1820 to 1875, block-buster innovations, especially the rapid expansions of the railroads, the emergence of coal-fired steamships to replace sailing vessels, and the invention of the telegraph, generated an annual growth rate for international trade that exceeded the growth of overall output by 3 percent. During the next 35 years, from 1875 to 1910, the growth rate of trade surpassed that of output by 1.7 percent per year. New technologies continued to appear—oil-powered ships, motor transport on land, telephone and radio communications—and existing ones improved. But their effects were less dramatic than the advances at the start of the period. Finally, in the 10 years following Angell’s book, from 1910 to 1920, trade grew only 0.3 percent per year more rapidly than output, as the impact of these innovations declined still further.

After 1920, globalization went into reverse for three decades. Certainly, the Depression, in the protectionist policies it spawned, and the great disruption of World War II played a role. But more important were underlying economic developments that changed the mix of outputs in a way that greatly reduced the overall significance of international trade.

Until 1920, the world economy was largely devoted to the production of commodities: raw food and other agricultural products, metals and other minerals, coal, bulk textiles. As late as 1920, expenditures on food accounted for more than 60 percent of total household spending in the United States. But a major shift was in process, a shift that accelerated after 1920. Differentiated manufactures—automobiles, household appliances, electrical equipment, processed foods—came to dominate household spending and economic output.

Two forces spurred this transformation. First, production in agriculture, mining, and metals became much more efficient. Rapid productivity growth drove down both prices and employment in these commodity industries. Even though physical output continued to expand, the value and economic significance of commodity products began a long decline. Second, incomes rose, thanks to improved productivity. Consumers could spend less for the same quantity of basic goods they had previously bought, leaving enough to buy the novel manufactured items that brought variety, convenience, comfort, and status into their lives.

This changing composition of demand affected international trade. The infrastructure of trade—transportation equipment, shipping lines, communications links, agency relationships, marketing programs—had evolved to handle the movement and distribution of commodities, which was uncomplicated. National differences in tastes and requirements for wheat, soybeans, steel, copper, coal, cotton, wool, and the rest were either limited or nonexistent. Shipping could be done in bulk. Prices were well-known and well-defined. Customized local marketing efforts and service support after the sale were rarely required. This system, designed for bulk commodities, proved inadequate to conduct trade in the differentiated manufactures that were capturing increasing amounts of consumer spending.

By their very nature, differentiated products respond to local tastes and specifications, like clothing styles and voltage requirements for electrical equipment. Prices are not set in global commodity markets; they depend on the success of local marketing efforts. So does sales volume. Shipping can require precise packaging and handling. And after-sale support for items like automobiles, appliances, and industrial equipment entails extensive local service and supply networks. It took time to set up this more elaborate commercial infrastructure, and until it was in place, trade suffered.

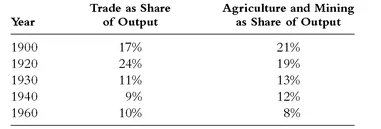

Both the changes in the composition of economic activity and the consequences for trade are apparent in data for the U.S. economy (Table 1.2). In the two decades from 1900 to 1920, agriculture and mining accounted for roughly 20 percent of U.S. economic output and between 30 and 40 percent of employment, although the employment figures were already declining because of rising productivity. Trade as a fraction of U.S. output increased from 17 percent in 1900 to 24 percent in 1920, a rate slightly faster than the global figures, which were depressed by World War I and its aftermath. Between 1920 and 1930, agriculture and mining fell from 18.5 percent of total U.S. output to 12.6 percent. The relative importance of trade also plummeted; from 24 percent of output in 1920, it dropped to just 11 percent in 1930. Over the next 30 years, trade remained at around 10 percent. Agriculture and mining continued their relative decline, falling to around 8 percent of output in 1960.

Table 1.2 Trade,Agriculture, and Mining in the U.S. Economy

SOURCE: Historical Statistics of the United States.

Starting in 1950, trade began a steady recovery from the depths to which it had sunk. Given what Adam Smith described as a propensity in human nature “to truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another,” it was only a matter of time before businesses learned to sell differentiated products in distant markets. The growth of multinational corporations in the period after World War II allowed branded products, like General Motors cars, Nike shoes, and IBM computers, either to be assembled from parts made in lower-cost manufacturing operations in foreign countries, or to be produced there entirely. Firms like Siemens, Daimler-Benz, Cadbury Schweppes, Néstles, and Sony acquired the skills to market their product globally. At the same time, a political climate generally favorable to international commerce permitted the steady reduction in tariffs and other barriers to international trade. (To put the importance of trade policy in perspective, we should bear in mind that a favorable government climate in the 1920s could not compensate for the effects of changes in the mix of economic activity, and that trade began to revive in the 1950s, well before the big reductions in barriers in the 1960s.) As a consequence, between 1950 and 1975, trade once again grew more rapidly than overall output, by a margin of over 2 percent per year (Table 1.1). And once again this growth was subject to diminishing returns. In the next 25 years, the advance of trade over output reverted to 1.2 percent per year.

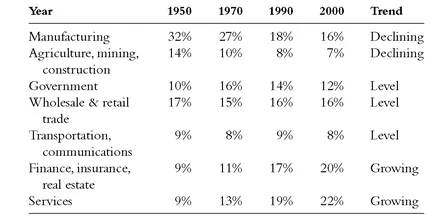

From Goods to Services

Since 1950, there has been a steady shift in global economic activity from differentiated manufactures to services, a transformation that mirrors the move early in the twentieth century from commodities to differentiated manufactures (Table 1.3). Manufacturing, which at the start of the period accounted for around 32 percent of economic output in the United States, had by 2000 declined by half, to just under 16 percent. If this trend continues, manufacturing will represent 4 percent of output in the United States by the end of this century, which is less than agriculture and raw material today. The share of the service sector, broadly defined to include transportation, communications, utilities, and government services, along with health care, education, retail sales, and all the other activities generally included, rose from 54 percent to 78 percent of the total economy during the same 50 years ending in 2000. Because these service goods are inherently more difficult to provide across national boundaries, continuing expansion of this sector will reduce the impact of globalization, much as the earlier growth of the complex manufactures did in the period after 1920.

Table 1.3 Share of GDP by Industry in the United States

SOURCE: Historical Statistics of the United States, Statistical Abstract of the United States.

Growth in productivity, this time in manufacturing, is again primarily responsible for this reordering of economic activities. This productivity growth has been rapid.Thanks to computer-based advances in automation, there is reason to think the pace will continue. Between 1980 and 2000, manufacturing productivity in the United States grew at an average of 3.4 percent per year, much faster than the overall annual increase of 1.8 percent in all nonfarm businesses. The gap has not closed in the years after 2000. As long as this trend continues, the relative prices of manufactured goods will fall, as will employment in manufacturing, even if demand for manufactured goods keeps pace with overall consumer demand.

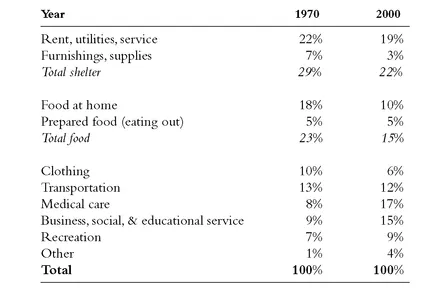

In fact, for many years, as incomes have risen, consumers have been increasing the share they spend on services and shrinking the share going to manufactures. In 1970, households in the United States spent 23 percent of their budgets on food, and about 80 percent of that (18 percent of the total) went to buy manufactured food products consumed at home (Table 1.4). By 2000, the total for food had fallen to 15 percent, only two-thirds of which (10 percent of the total) was for eating at home. Clothing expenditures followed the same downward path, as did shelter costs, especially those for home furnishing and household supplies. Moving upward to take up the slack was increased spending on medical care and business, social, and educational services .5

Table 1.4 Consumption Expenditures in the United States (as share of total)

SOURCE: Statistical Abstract of the United States.

Older and richer people spend relatively more of their incomes on housing, education, medical care, and other services. As the population ages and becomes wealthier, these are almost certainly going to continue increasing their share of overall household consumption. Thus, trends in demand in favor of services will reinforce underlying trends in increased productivity and lower costs in manufacturing. The future of manufacturing will look like the past of agriculture and the extractive industries, and it will become an increasingly marginal part of the overall economy, even though there will be no shortage of manufactured goods.

What will this mean for the future of globalization? Manufactures have historically been easier to trade than services, which, in the great majority of cases, are produced and consumed locally, like housing and medical care. If this pattern continues to hold, then we are at an inflection point similar to that of the early 1920s, after which globalization became a diminishing factor in the world economy.

Thomas Friedman, Clyde Prestowitz, Robert Shapiro,6 and a number of other writers on the subject have argued the opposite.They foresee advances in information technology and communications that will allow—or compel—services to follow the historical path of differentiated manufactures and be provided across national borders as easily as toys, tractors, and topcoats. Don’t count on it. A precise examination of the kinds of services that are likely to be in demand in the future suggests that they will be difficult to globalize.

Which Services Remain Rooted?

The largest single area of consumer demand is shelter, including housing and related services and products. By its very nature, housing itself must be supplied locally. Unless Americans, Europeans, or Japanese live in India or China, they will not be offshoring their housing needs. Utilities, household improvements and repairs, and home maintenance services must also be provided locally. Some services, like security monitoring, may be done from abroad, but the installation will be a local service, as will emergency response...

Table of contents

- Praise

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 - It May Be News, But It Isn’t New

- Chapter 2 - Countries Control Their Fates

- Chapter 3 - Employment Trends for Globalization 3.0

- Chapter 4 - Can We Make Any Money?

- Chapter 5 - International Finance in a Global World

- Chapter 6 - A Genuine Global Economic Problem

- Conclusion

- Notes

- About the Authors

- Index