- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

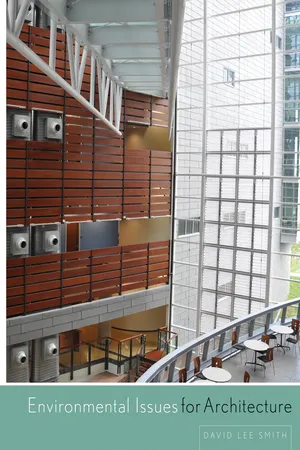

Environmental Issues for Architecture

About this book

This primer for architects explores the basic physical principles and requirements of every aspect of passive and active controls in buildings. Avoiding needless jargon, Environmental Issues for Architecture supports an understanding of environmental systems in order to inform architectural design. With topics ranging from lighting, acoustics, thermal control, plumbing, fire protection and egress, to elevators and escalators, all of the latest technologies are supported. Designer-friendly, this rich resource gives just enough technical information for architects to design buildings that are efficient and comfortable.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

ENVIRONMENTAL AESTHETICS

THE INTENTIONS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN

CONCLUSION

INTRODUCTION

This book presents basic information about the major environmental issues that impact on architectural design and attempts to do so in a manner that can guide and support the design process. These presentations are not intended merely to cover “required” information before they must be addressed, which for too many design projects done in school is during preparation of the presentation drawings. Unfortunately, the inclusion of environmental considerations often tends to be merely applied “window dressing” intended to make a project appear more “architectural.” While there are legitimate reasons why an expansion of items addressed occurs at presentation time, an understanding of environmental issues, particularly in terms of concepts and principles, must be present at the beginning of the design process so that it can inform the initial schematic explorations. A response to the critical environmental issues must be at the core of any effective design, not merely an applied accommodation added later.

With an increased understanding of the basic concepts and principles of the different environmental topics, we should be better able to grasp the connection between these critical issues and effective architectural design. Although the presentation of these issues might at times be mathematical, these issues are definitely not external to effective design, nor should they be considered only as corrective measures that allow one to do something illogical in terms of design. In fact, an understanding of these principles is fundamental to design.

Unfortunately, the obvious significance to design of some of the material covered in this book might not become fully apparent until later in your studies or perhaps not until later in your design careers. But as with most of what we study, if we understand the underlying principles, these explorations of environmental issues will continue to be of value as we progress in our studies and throughout our professional careers.

ENVIRONMENTAL AESTHETICS

Nature can only be mastered by obeying its laws.

Roger Bacon (Thirteenth-century English philosopher and scientist)

Esthetic judgment constitutes the quintessential level of human consciousness.

James M. Fitch (Architectural historian and theorist)

The commitment of environmental designers (interior designers, architects, landscape architects, and urban designers) to the enhancement of the human experience can best be realized through designs that are both aesthetically pleasing and socially meaningful. In this effort, perhaps the most confusing task is to assign the proper significance to each concern so that the resulting design responds appropriately to the imposed conditions. To accomplish this effectively, designers must have an understanding of science and technology in addition to sensitivity for composition and form.

Science is much more than a body of knowledge. It is a way of thinking. This is central to its success. Science invites us to let the facts in, even when they don’t conform to our preconceptions. It counsels us to carry alternative hypotheses in our heads and see which best match the facts. It urges on us a fine balance between no-holds-barred openness to new ideas, however heretical, and the most rigorous skeptical scrutiny of everything—new ideas and established wisdom.1

Carl Sagan (Renowned American scientist)

Many erroneously believe that science is based primarily on complex mathematical computations, and because of this, there is often a tendency to assume that science is imbued with a notion of certainty. On the other hand, art is generally considered to be nonspecific and nonscientific. As a result, designers often tend to avoid specific limitations, especially if they are expressed through the use of numbers, as if the acceptance of specificity might imply that they are not really concerned with the poetry of design or, even worse, that they are not really creative.

Calculations, the use of mathematical formulas, are merely a way to model certain aspects of the physical world. Math is a language that provides a simple way of expressing ideas, but many designers are uncomfortable with the mathematical language and cannot appropriately appreciate or effectively use a mathematical model. While rejection of mathematics is unfortunate, since it deprives designers of an effective means of modeling certain conditions, it is untenable if it encourages designers to concomitantly reject science or to go as far, as some do, as to exclaim, “Don’t confuse me with the facts!”

Science is the ever-unfinished task of searching for facts, establishing relationships between things, and deciphering laws according to which things appear to occur. The main intention of science is to extract from the chaos and flux of phenomena a consistent, regular structure––that is, to find order. Similarly, effective environmental design should be committed to the discovery of pattern, structure, and order and to giving them viable expression in physical form.

Today there is some confusion over what is or should be the basic intentions of environmental design. This confusion is probably the result of various changes that began developing as long as 150 years ago with the general industrialization of the construction field. This industrialization has tended to separate the design process from what James Marston Fitch called “the healthy democratic base of popular participation.”2 As a result, the designer is now typically isolated from the consumer, increasing the “prevalence of the abstract, the formal, and the platitudinous in architectural design.”3 It is becoming increasingly clear that an attitude within many segments of the various design professions is “one of complacent laissez faire whose esthetic expression is a genial eclecticism. The result is a body of work as antipopular and aristocratic in its general impact as anything ordered by Frederick the Great or Louis XV.”4

While many of the prominent voices in the design field seem to be consumed by a theoretical dialogue on stylistic intentions and priorities, the traditional leadership role that environmental designers have traditionally contributed has been significantly reduced. In fact, in many situations, oblivious to their fundamental responsibility to ensure that environmental development is nurturing and sustainable, the work of many designers continues to degrade rather than enhance the natural environment. At a time when the design professions should be actively involved in supporting rational, sustainable development, continued infatuation with a narrow set of design parameters might reasonably be interpreted as equivalent to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic.

Rather than narrowing our options, design professionals should be pursuing ways both to maintain traditional involvement in environmental design and to increase the level of participation through an expansion of professional services. We should take the opportunity to build upon the problem-solving methodology of the design field and substantially extend its realm of engagement. We should reinterpret the basic notion of what constitutes environmental design practice, and sustainable development provides a means to accomplish this.

The ultimate and quintessential role of environmental design is the interpretation of ideas through physical form for human habitation, and designing is the actual act of interpretation. The idea of the designer as a creative individual operating intuitively and independently in this effort of interpretation, although romantic, is unsubstantiated by fact and is a notion that inhibits realization of the architectural potential. While designing is obviously a critical responsibility of professional practice, there are numerous activities with which designers have regularly been involved and upon which designing relies. Just in terms of traditional architectural practice, these usually include promoting and selling architectural services; educating the public, clients, and future professionals; preparing a project brief; developing contract documents; selecting contractors and determining costs; and inspecting construction progress. In addition to these activities, there are a number of allied services that are frequently associated with architectural practice.

Although these various activities collectively constitute the overwhelming portion of architectural practice, a presumption remains, even among many practicing architects, that designing is the most dominant aspect of professional architectural services. In reality, designing accounts for only around 10% of the actual effort expended in fulfilling the demands of most architectural practices! While the actual act of interpretation is critical, all efforts necessary to accomplish this interpretation are essential and crucial to the architectural endeavor, not merely the interpretation itself.

Regrettably, a distinction is sometimes made between the value and importance of “designing” and the “nondesign” efforts of contemporary environmental practice. This establishes an unfortunate hierarchy within the design professions that is extremely divisive and can undermine collaboration, which is essential for effective design that is responsive to the multiplicity of concerns in our complex world. While distinctions in the areas of involvement will remain, any assumed hierarchy will continue to be extremely disruptive to the environmental design professions. To remain effective, we can no longer indulge ourselves with a biased, myopic view of what is actually an extremely diverse responsibility that demands multiple skills and abilities.

Too many recent “prestigious” buildings have been designed in response to a rather narrow value system. While some of these buildings are clearly attractive, too often they are void of functional meaning or any significant social connotation. Only with an understanding of the technological propriety, tempered by a process of socialization, can the environmental design professions move from their recent role of “agent and spokesman for the elite”5 to achieve more meaningful contact with and support for the popular community.

An understanding of technological propriety can only come from a sound theoretical scientific foundation. As Gary Stevens stated in The Reasoning Architect:

. . . although architecture is usually thought to be the product of acts of inspired creation, it is also the product of acts of inspired reason; to demonstrate that science and mathematics are portions of our intellectual culture that cannot be set apart from architecture and left to the engineers to worry about, but are the concern of all of us.6

A distinction is often made also between art and craft. These dichotomies are in fact quite recent, about 200 years old, but as long as we do not take the boundary as hard-and-fast, and admit into each parts of the other, they are useful distinctions if only because scientists and artists do see themselves as carrying out quite different sorts of activities.

Though they may be different, it does not necessarily lead to the conclusion that they are opposed. The two can be unified in the one individual or pursuit.7

It is unfortunate, and perhaps even harmful, that in our society, art and science have come to be seen as opposites and antagonistic to one another. Perhaps this tension between the two cultures of art and science is most evident in the environmental design disciplines––that is, in architecture, broadly defined to include physical design extending from consideration of interior space to the urban environment. This confrontation between art and science is especially disturbing since effective environmental design depends on a collaboration of the two.

The wide-ranging criticism of science in architecture is based on the notion that science demands that design be predicated on the application of a set of operational rules that are devoid of any concern for humanistic values. But this criticism is founded on a fundamental confusion about the meaning of humanism and the nature of science. As expressed by Jacob Bronowski:

The scholar who dismisses science may speak in fun, but his fun is not quite a laughing matter. To think of science as a set of special tricks,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION

- Chapter 2: LIGHTING PRINCIPLES

- Chapter 3: LIGHTING CALCULATIONS

- Chapter 4: DAYLIGHTING

- Chapter 5: ACOUSTICS

- Chapter 6: THE THERMAL ENVIRONMENT

- Chapter 7: THERMAL CALCULATIONS

- Chapter 8: HISTORIC REVIEW

- Chapter 9: ECS DESIGN INTENTIONS

- Chapter 10: ENVIRONMENTAL CONTROL SYSTEMS

- Chapter 11: PLUMBING

- Chapter 12: ELECTRICITY

- Chapter 13: FIRE PROTECTION AND EGRESS

- Chapter 14: ELEVATORS AND ESCALATORS

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Environmental Issues for Architecture by David Lee Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.