- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Understanding the flexibility and limits of behaviour is essential to improving both the horse's welfare and its performance. This book tackles the fundamental principles which will enable owners, riders, trainers and students to understand scientific principles and apply them in practice. Subjects covered include the analysis of influences on equine behaviour, the perceptual world of the horse, learning and training techniques including the latest developments in "join-up" and "imprint training".

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

Understanding Behaviour Concepts

In this section we introduce the principles behind the study and interpretation of animal behaviour. Anyone can watch animal behaviour but that is not the same as making a scientific study of it. In order to do this, we must understand and apply certain rules. An explanation of these helps us to understand why a horse behaves in a certain way, as well as why it does not behave in another way (the limits of its behaviour). These limitations are just as important when we consider how we should manage our horse best. With such understanding we are also in a position to test our own ideas scientifically with either field or laboratory experiments. This is the way in which scientific knowledge increases and our understanding of the needs of the horse improves.

1

Approaches to the Study of Behaviour

We may be motivated in our study of behaviour by the hope that we can improve the performance of our own horse in some particular way, seeking to make it do what we want, but in studying horse behaviour and its origins and management in general terms, we should not forget that not all horses are winners. You may be disappointed that the horse you had high hopes for turns out to be completely talentless, despite your strenuous efforts to ‘understand’ him. The problem may not lie with the method used, but with the potential of the horse. In other words, the horse’s behaviour is a product of both its biology and its environment or ‘nature and nurture’, as many people call it. We should not get so wrapped up in our role in ‘nurturing’, that we forget about the ‘nature’ of horses in general and that horse in particular.

What is behaviour?

Behaviour is what living animals do, and what dead animals don’t do. Behaviour is an expression of physiology. There are two broad ways in which we tend to describe behaviour:

(1) We can detail the physical actions involved in a behaviour; how one part moves relative to either another part of the body or the environment. For example, we might say that a horse has extended its foreleg, or that it is galloping.

(2) Alternatively we may describe the consequences of the behaviour or the suspected aim. For example, we might say that one horse is threatening or attacking another. This will often involve an element of interpretation, which can cause problems.

A horse dozing in a field is performing just as much behaviour as a horse that is fighting, riding a bike, or turning somersaults! These are all complex actions which involve the integration of several behavioural acts. The mechanism that allows a horse to sleep standing up is, in itself, a really neat piece of engineering. Contrary to popular belief, however, horses still need to spend a certain amount of time lying down in order to sleep properly. Management can have an effect on even this. Houpt (1991) reports that horses which are usually stabled sleep less for the first month after turn out, and do not even get down to sleep on the first night. Since sleep is essential for the normal functioning of an animal during its waking hours we should not be surprised if the performance of the horse is affected by such a management change. This simple example highlights an important theme: we cannot understand an animal’s behaviour without referring to its environment. Horses do certain things in certain environments.

Why do horses gallop?

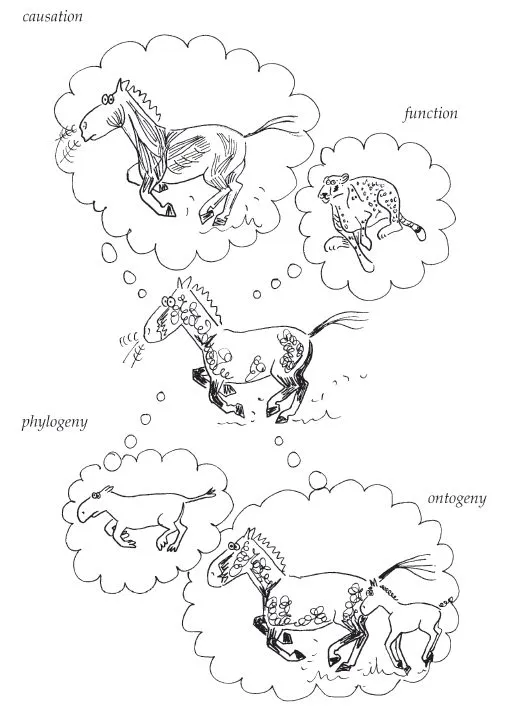

Niko Tinbergen pointed out that if we wanted to know why an animal performs a certain behaviour, there are always four very different, but equally correct answers. For example, if we ask the question, ‘why do horses gallop?’ the answer could be:

◊ ‘Because nerve impulses from the brain and spinal cord lead to muscle contraction in a co-ordinated way to bring about the galloping gait’.

We could go even further by saying that the nerve impulses and muscle contractions occurred because of certain physiological and biochemical changes, and give a string of chemical equations in order to explain why the horse was galloping. This is the most basic answer, looking at the horse as though it were a piece of machinery. This answer, where the idea is to try and explain the behaviour in terms of its immediate cause and control, explains the causation of behaviour.

◊ ‘Because during its early development the foal learned how to co-ordinate its limbs and body to allow it to gallop’.

This approach is to explain the behaviour in terms of the developmental history (the ontogeny) of the behaviour within an individual.

◊ ‘Because, over millions of years, those ancient relatives of the horse which did not move so quickly and efficiently lost out and left no descendants. Horses gallop because that is how they have evolved to move most efficiently at high speed.’

This explains the behaviour in terms of its development not within an animal’s lifetime history but within the history of the species. The evolutionary history of a behaviour explains how it is adapted to its environment and is often referred to as its phylogeny.

◊ Because galloping is the best way for a horse to avoid a predator’.

This offers an explanation as to the function of the behaviour. The function of the behaviour tells us its survival value.

The first two answers explain how a horse manages to gallop, whilst answers three and four consider the purpose of galloping, but they are all correct. When asking ourselves ‘why does...?’, we must appreciate that there are several different approaches and several answers. In order to understand behaviour fully we need to recognise and understand these four different approaches.

Fig. 1.1 Answers to Tinbergen’s four questions.

Ethology versus psychology

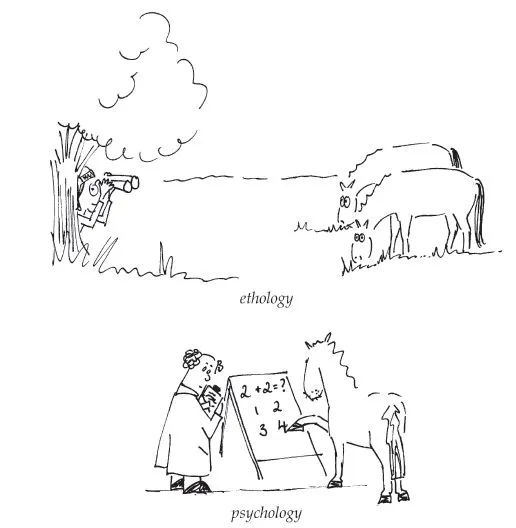

The study of behaviour therefore requires the application of several biological sciences. Traditionally these have been focussed into two broad overlapping disciplines, each with a different emphasis: ethology and psychology.

The early ethologists were mainly involved with the study of wild animals in their natural environment, believing that the forces of evolution had adapted the behaviour of animals. Ethologists, therefore, tended to concentrate on those aspects of behaviour which were inherited from one generation to the next, especially the genetic aspects of behaviour. Niko Tinbergen (1952) wrote: ‘Learning and many other higher processes are secondary modifications of innate mechanisms’. To him and other early ethologists the nature of inherited behaviour was its most important feature.

Early psychologists, on the other hand, were more interested in the development of behaviour within the individual, and concentrated on trying to establish general and universal laws affecting behaviour and how it changes with learning. In this case one species of animal was often considered as good as another for modelling the general behaviour mechanisms of animals. They tended to emphasise the importance of the environment and nurturing. This is typified by the words of one of the most famous early psychologists, John Watson:

’Give me a dozen healthy infants, well formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one of them at random and train him to become any specialist I might select: doctor, lawyer, merchant, chief and yes, even beggar man and thief, regardless of his talents, peculiarities, tendencies, abilities, vocations and race of his ancestors.’ (Watson 1913).

Because they were interested in different aspects of behaviour ethologists and psychologists had very different ways of studying it.

In the first half of the twentieth century furious arguments raged on the nature–nurture debate: psychologists demonstrated how flexible and changeable ‘instinctive’ behaviours were, and ethologists showed how animals would inherently respond to certain stimuli without learning. It is only as recently as the 1970s that the two sides really accepted that they were both making valid contributions, and that most progress would be made if they put their heads together.

Fig. 1.2 Different approaches to the study of animal behaviour.

The modern synthesis

The disciplines of psychology and ethology not only complement each other well but are inextricably linked. You cannot have behaviour without both nature and nurture. Behaviour is the consequence of the constant interaction of genetic factors with the environment; a process called epigenesis. Indeed, we could describe behaviour as a phenotypic characteristic, just like size or coat colour. Unlike other phenotypic characteristics, however, behaviour is variable on a day-to-day, or even a minute-by-minute basis.

McFarland (1993) suggests that the environment and genetics are to behaviour what length and breadth are to a field. You cannot have a field without both of these dimensions. We should resist the temptation to talk about behaviour patterns being either genetic or learned, as if only one of these factors were important in determining behaviour. The combination of genetics and the environment sets the limits for the behaviour, just as length and breadth determine the boundaries of the field. They set the limits of an individual’s ability and suggest certain predispositions. You would not go out and buy a Shetland pony from a children’s farm if you had set your sights on getting round Badminton.

The constant remoulding of an animal’s inherent behavioural tendencies by its environment is important from a training aspect. Horses do not just ‘behave’ because ‘that’s the way they are’, they respond to their environment according to their abilities. In attempting to train the horse, we become part of its environment. This is a big responsibility, which we must be prepared to accept if we hope to be able to tap the horse’s ability. We must make an effort to understand why a horse behaves in a particular way, and not just try to manipulate the results of the behaviour we see.

Techniques developed for studying behaviour in one discipline have also been borrowed by the other and resulted in great advances in our scientific understanding of behaviour. For example, the techniques used by psychologists to assess how animals respond to different rewards have been used to understand how animals naturally regulate their behaviour (see Kacelnik (1984) for experimental details). This has also helped us develop techniques to assess what is important for their well-being in captivity, as discussed in Chapter 10.

So what is behaviour?

We have already suggested that behaviour is a phenotypic feature, i.e. it is the result of the interaction between the environment and genetics at any given moment in time. We have also suggested that both the recent (proximate) and historical (ultimate) factors affecting it can be investigated. Recent factors include its immediate value and causation; historical factors include developmental issues. In both these cases behaviour is a means whereby an animal can adapt to its environment. In the short-term sense we can view behaviour as an external manifestation of internal physiology. A change is detected in the internal or external environments and this is processed by the animal which results in a change of behaviour. In order to understand behaviour, we must appreciate all these issues. With this understanding we are able to assess better how we manage horses and how we can improve. But first we must make sure that we study behaviour in a scientifically rigorous way.

A brief guide to conducting a behaviour study

The objective nature of data

Jennings, a behaviour physiologist, wrote in 1906,

for those interested in the conscious aspects of behaviour, a presentation of the objective facts is a necessary preliminary to an intelligent discussion of the matter.

These words are not only applicable to conscious behaviour but also to any scientific study of animal behaviour. We all have our ideas as to why an animal does something in a particular way and what horses really get up to. The value of good science is that it allows us not only to offer an explanation of why something has occurred but also to predict why, when or how something is likely to recur. This means that we can prepare better for the future. Many people report their observations and feelings on all sorts of matters, but only if they are scientific can we really appreciate their true significance and compare them to other data. The scientific study of behaviour involves being as objective as possible about our observations. When we study behaviour we are interested in gathering data and this is the first of many problems we must overcome. Data are unbiased measurements. We can listen to a horse’s heart and count the number of beats. The number we have is then a piece of data. If we report that the horse’s heart seems a bit fast, this is not real data, but an interpretation of data. The horse may have recently run a race, have a fever, be a little nervous about us listening to its chest or just naturally have a higher than average heart rate. Only if we have more information can we interpret our data properly. It is therefore essential that we gather all the appropriate information in our study, before we discuss or try to interpret our results.

Descriptive and experimental studies

There are two broad types of behaviour study.

(1) There are those that describe and report what is happening, and so we have a record to which we may later wish to refer. This tells us what is happening in the world of horses.

(2) The second type of study is a form of experiment. We start with a question to which we want an answer. From this we think of a range of possible explanations. The aim then is to work out an experiment that would let us distinguish between them. We then gather our data and see which ideas we can discard. This does not mean that we have proved any that are left, since there may be other explanations which we had not thought of and which could not be disproved by the experiment. This is an essential point in science which is commonly misunderstood. We do not go out to prove our ideas, we try to disprove all the alternatives.

A simple example will illustrate the point. Suppose we are interested in why horses crib-bite. We might suppose that horses do this in order to pass the time of day as there is little else for them to do in a stable (some might call this boredom). Alternatively, we might argue that they do it because they are very frustrated by being kept in the stable, particularly around meal times. At this time they can see their food but cannot get to it. We could possibly distinguish between these two explanations by giving a group of horses a toy containing food. This means that they have to work quite hard to get their ration. If the first explanation of cribbing is true then we might expect the amount of cribbing to go down when the toy is introduced. If cribbing is associated with frustration, then giving a horse a source of food which it cannot easily get to may be more frustrating. Horses are grazers and so may not be adapted to having to work for their food in the same way that a dog or cat has to. In this case we might expect the cribbing to get worse or stay the same but certainly not to get any better. An experiment somewhat similar to this has been done ( Henderson et al. 1997). What they found was that some horses got better and others got worse. What does this tell us about why horses crib? Probably that there are several very different reasons why horses have this disturbing behaviour. Even if they had all responded the same way we could not say we now knew why horses crib. At best we could say why they probably do not.

Science can be very frustrating at times, but it can also be very exciting as you realise that there is so much that we still do not know. In this example the experimenters were measuring behaviour in order to test an idea, but whatever its purpose information needs to be gathered in a scientific manner.

Measurement

A horse’s behaviour is a continuous process. As long as it is alive it is behaving. We can however divide behaviour into discrete units like galloping, chewing and kicking. When we use terms like these it may seem obvious to us what the horse is doing, but, as with any measure, like a metre, hand or second, we must ensure that we are using the term in a way which other people understand. If I say tha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Part 1: Understanding Behaviour Concepts

- Part 2: Mechanisms of Behaviour

- Part 3: The Flexibility of Behaviour and its Management

- Appendix

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Equine Behaviour by Daniel S. Mills,Kathryn J. Nankervis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Equine Veterinary Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.