![]()

Part 1

Tools of the Trade

Part 1 requires the working knowledge of certain important disciplines that are firmly footed in the mathematical and economic sciences. Any financial analyst needs to study these disciplines—work with them time and time again—before being ready to progress farther into the financial analysis maze. As with many other professional pursuits, most of the early work (grunt work, “paying your dues,” “coming up the ladder”) builds a foundation on which the higher skills depend. They are the building blocks that the investor will use countless times in the construction of a portfolio.

The tools of financial analysis are as critical to investment success as surgical instruments are to a brain surgeon. With a working knowledge of these tools, the financial analyst, whether a beginner or a seasoned investor, will have the skills to recognize a timely investment opportunity.

The four tools of financial analysis are:

1. Accounting

2. Economics

3. The mathematics of finance

4. Quantitative analysis using basic statistics and regression analysis

In Chapter 1 we discuss the all-important science of accounting, or as we call it—“the scriptures of business.” Accounting is the written language of business—the figures that bring it all together and the universal language an analyst uses to understand the business. A working knowledge of accounting enables the investor to dissect the company’s financial statements to better understand the specifics within a business as well as searching for any inconsistencies or red flags. In this case, the investor acts as a detective, searching through data from sources initiated by several types of media, to identify information that permits an analysis and subsequent valuation.

Additionally, careful examination of financial statements can lead to a better understanding of management’s policies and style: Answering such questions can lead to a more comprehensive valuation of any company.

Does management have a conservative or liberal bias with regard to accounting policies? By which method are non-current assets depreciated? What is the “quality” of the earnings? How are the revenues determined? What methods are employed?

Chapter 2, “Economics,” focuses on the items, such as government indicators and the important parity conditions that exist in international economics. Studying these areas is essential for attaining a more complete picture of how economic events affect the valuation of financial instruments:

When are the major economic indicators released and what do they tell us about the economy? Does the economic business cycle permit an advantage in timing of the stock market? What role does the Federal Reserve play in the conditioning of our financial markets? How have the theories of economic science differed in the past 100 years?

Chapter 3, “Investment Mathematics,” deals with the underpinnings of the entire study of investment finance—the mathematics behind the future value of money. After a discussion of the different formulas used to calculate this all-important mathematical concept, several problems are presented that permit the practitioner a repetitive learning format. This “problem set” format lends itself to much of this chapter, for investment mathematics, simple enough in theory, requires the practical understanding that comes with repetitive problem solving (e.g., What is the future value of $1,000 in 6 years at a compounded rate of 6 percent per year? What is the internal rate of return, or valuation, of a specific investment project?).

Chapter 4, “Quantitative Analysis,” is the final chapter in Part 1. The quantitative approach to investment analysis is critical when the investor is making a hypothesis about the relationship between independent variables and a particular firm’s earnings. This chapter also discusses the differences between simple and compounded annual returns so to better evaluate the returns quoted in the financial press and within the industry. Again, the problem set format is used to further reinforce the practical applications of this theory (in addition, the appendix in Chapter 4 covers regression analysis).

Okay, so let’s buckle up our tool belt and begin this journey into the world of Security Analysis.

![]()

Chapter 1

Accounting

In this chapter, you will learn the following aspects of accounting:

• The big three: the balance sheet, the income statement, and the cash flow statement.

• The basics of managerial accounting.

The practice of accounting is the tabulating and bookkeeping of the capital resources (in currency terms) of a particular firm. The actual entries listed on the accounting statements do not tell us anything concrete about the firm’s business activities, but reflect how accountants record these activities. That is not to say that accounting statements are without value; they are among the most important pieces in the valuation puzzle, but without careful study, they do not reveal any information of consequence. This inadequacy of accounting data lies within the procedures themselves; in most cases, an investor needs to be proficient in this art to gain any insight into the future prospects of the concern in question.

The Big Three

The financial statements of a business enterprise are essentially their scribes—the books, as we affectionately call them. These “books” document—in the universal language of numbers—the ins and outs of the flow of capital within a business enterprise. The books come in three chapters, if you will: the balance sheet of assets and liabilities, the income statement of revenues and costs, and the cash flow statement which reconciles the inflows and outflows of cash. These three statements are interlinked, as we will soon see, and their interaction—and the understanding of the implications between each statement—is a critical part of the analyst’s core competency. In the sections that follow we discuss each statement in detail.

The Balance Sheet

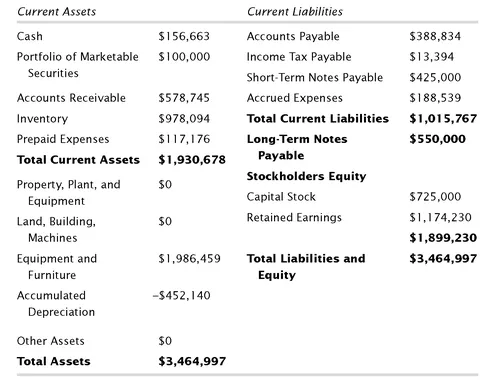

The balance sheet serves as a snapshot of the current net worth of a particular firm at a given moment in time. It illustrates, in some detail, the asset holdings (fixed and current) as well as the liabilities, in such fashion that the offsetting amounts equal the net worth of the company (equity). In its simplest form, the Balance Sheet offsets the enterprise’s assets (the value of things they own) with the liabilities (the value of things they owe), which results in the equity (the net worth) of the enterprise. As we will see, the key in this statement is how these assets and liabilities are valued—this will give the analyst and investor keys to unlocking value opportunities or red flags of caution. When examining the balance sheet be mindful of the inputs—in other words, how these values came to be—for, as in many business pursuits, the devil is in the details. These details are compiled in the often forgotten “fine print” of the footnote section of the accounting documents. It is here, in these footnotes, that the perceptive analyst (“detective”) can uncover opportunities and important issues. The following definitions provide an understanding of this financial statement’s individual components. (See Table 1.1 for a sample of this statement.)

Assets

The first major section of the balance sheet lists assets, including the following:

Current Assets This consolidation entry includes assets that can be converted into cash within one year or normal operating cycle. The following entries are components of current assets:

TABLE 1.1 ABC Products—Balance Sheet 12/31/08

• Cash. Bank deposit balances, any petty cash funds, and cash equivalents (money markets, U.S. Treasury Bills).

• Accounts receivable. The amount due from customers that has not yet been collected. Customers are typically given 30, 60, or 90 days in which to pay. Some customers fail to pay completely (companies will set up an account known as “reserve for doubtful accounts”), and for this reason the accounts receivable entry represents the amount expected to be received (“accounts receivable less allowance for doubtful accounts”).

• Inventory. Composed of three parts: (1) raw materials used in products, (2) partially finished goods, and (3) finished goods. The generally accepted method of valuation of inventory is the lower of cost or market (LCM). This provides a conservative estimate for this occasionally volatile item (see Aside on page 30: LIFO versus FIFO).

• Prepaid expenses. Payments made by the company, in advance of the benefits that will be received, by year’s end, such as prepaid fire insurance premiums, advertising charges for the upcoming year, or advanced rent payments.

Fixed Assets (Noncurrent Assets) Assets that cannot be converted into cash within a normal operatin...