![]() PART 1

PART 1

Basic Theoretical Elements, Instrumentation and Classical Interpretations of the Results![]()

Chapter 1

Kinematic and Geometric Theories of X-Ray Diffraction

When matter is irradiated with a beam of X photons, it emits an X-ray beam with a wavelength equal or very close to that of the incident beam, which is an effect referred to as scattering. The scattered energy is very small, but in the case where scattering occurs without a modification of the wavelength (coherent scattering) and when the scattering centers are located at non-random distances from one another, we will see how the scattered waves interfere to give rise to diffracted waves with higher intensities. The analysis of the diffraction figure, that is, the analysis of the distribution in space of the diffracted intensity, makes it possible to characterize the structure of the material being studied. This constitutes the core elements of X-ray diffraction. Before we discuss diffraction itself, we will first describe the elementary scattering phenomenon.

1.1. Scattering by an atom

1.1.1. Scattering by a free electron

1.1.1.1. Coherent scattering: the Thomson formula

The scattering of X-radiation by matter was first observed by Sagnac [SAG 97b] in 1897. The basic relation expressing the intensity scattered by an electron was laid down the following year by Thomson [THO 98d].

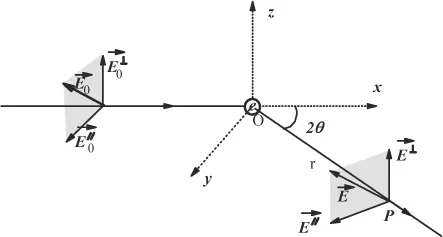

Consider a free electron located inside a parallel X-ray beam with intensity I0. This beam constitutes a plane wave traveling along the x-axis, encountering a free electron located in O. The electron, subjected to the acceleration:

starts vibrating and emits an electromagnetic wave whose electrical field vector is written, in P, as:

where e is the charge of the electron, m is the mass of the electron, r

e is the radius of the electron,

is the angle between

and

, and r is the distance between O and P.

Therefore, we obtain a wave traveling through P with the same frequency as the incident wave and with amplitude:

The vector

can be decomposed in two independent vectors

and

. The expression for the amplitude of vector

is:

, which is the corresponding intensity in P, is defined as the flow of energy traveling through a unit surface located in P over 1 second. The ratio of the incident and scattered waves in P is equal to the squared ratio of the amplitudes of the electrical fields; therefore we have:

The unit surface located in P is observed from O with a solid angle equal to 1/r

2. Therefore, the intensity in question, with respect to the unit of solid angle is

. Likewise, the intensity along the Oy-axis is given by

.

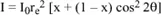

Any incident beam will be scattered with the proportions x and (1 – x) along the directions Oz and Oy and thus the total intensity in P can be written as:

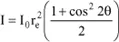

If the beam is not polarized, then x = 0.5 and therefore:

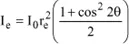

From now on, we will refer to this intensity as Ie and therefore we have:

This relation is called the Thomson formula [THO 98d]. It has a specific use: the scattering power of a given object can be defined as the number of free and independent electrons this object would have to be replaced with, in order to obtain the same scattered intensity.

1.1.1.2. Incoherent scattering: Compton scattering [COM 23]

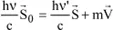

In addition to the coherent scattering just discussed, X photons can scattered incoherently, that is, with a change in wavelength. This effect can be described with classical mechanics by considering the incident photons and the electrons as particles and by describing their interactions as collisions, as shown in Figure 1.2.

and

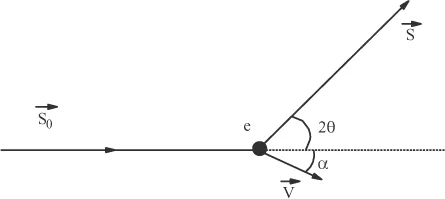

are the unit vectors of the incident and scattered beams, 2θ being the scattering angle, m the mass of the electron and V the electron’s recoil velocity once it is struck by the photon. If the vibration frequencies of the incident photon and the scattered photon are denoted by ν and ν’, respectively, the energy conservation principle leads to the relation:

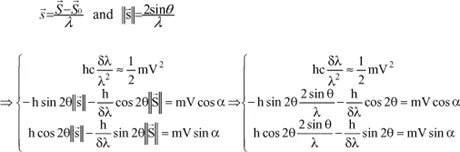

By applying the momentum conservation principle, we get:

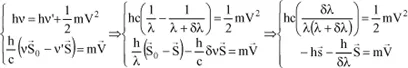

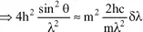

Calculation of the difference in wavelength between the incident wave and the scattered wave

By using the two principles just applied, we will be able to calculate this difference δλ, since we have:

with:

because

is a unit vector.

and finally:

Therefore, the variation in wavelength is independent of the initial wavelength and increases with θ.

In the case of a free electron, nothing prevents it from moving, since it is subjected to no outside force. Hence, the predominant effect is Compton scattering. However, it can be shown that the intensity of this scattering effect is accurately described by Thomson’s relation. When considering a set of free electrons, the different waves scattered by these electrons have different wavelengths and therefore do not lead to interference effects. What we observe is merely the sum of the scattered intensities.

1.1.2. Scattering by a bound electron

In an atom, an electron can assume different energy states. If, during the interaction with the X photon, the state of the electron does not change, then the photon emitted by the atom has the same energy as the incident photon. Hence, the resulting scattering is coherent (Thomson scattering). On the other hand, if the electron’s energy level changes, the scattered photon has a different energy and therefore a different wavelength from those of the incident photon: this is incoherent scattering. It means that by irradiating an atom with an X-ray beam whose energy is insufficient to cause electronic transitions, what we will observe is, for the most part, coherent scattering. Throughout this book, we will assume that this is the case.

Generally speaking, it can be shown that the total intensity scattered by a bound electron is equal to the coherent intensity scattered by a free electron, as given by the Thomson formula. This result can be expressed by the relation:

Calculating the intensity of coherent scattering

Each electron moves about in an orbital and, if

denotes the charge density of the bound electron in any elementary volume dV of this orbital, vector

being the one shown in

Figure 1.3, then

is expressed as

, where

is a wave function which is a solution to the Schrödinger equation.

Since the volume dV contains the charge ρdV, it scatters an amplitude equal to the one scattered by one electron multiplied by ρdV. If we consider coherent scattering, the waves scattered by each elementary volume dV interfere, because they have the sa...